This is the blog of Ian Rosales Casocot. Filipino writer. Sometime academic. Former backpacker. Twink bait. Hamster lover.

The Boy The Girl

The Rat The Rabbit

and the Last Magic Days

Chapbook, 2018

Republic of Carnage:

Three Horror Stories

For the Way We Live Now

Chapbook, 2018

Bamboo Girls:

Stories and Poems

From a Forgotten Life

Ateneo de Naga University Press, 2018

Don't Tell Anyone:

Literary Smut

With Shakira Andrea Sison

Pride Press / Anvil Publishing, 2017

Cupful of Anger,

Bottle Full of Smoke:

The Stories of

Jose V. Montebon Jr.

Silliman Writers Series, 2017

First Sight of Snow

and Other Stories

Encounters Chapbook Series

Et Al Books, 2014

Celebration: An Anthology to Commemorate the 50th Anniversary of the Silliman University National Writers Workshop

Sands and Coral, 2011-2013

Silliman University, 2013

Handulantaw: Celebrating 50 Years of Culture and the Arts in Silliman

Tao Foundation and Silliman University Cultural Affairs Committee, 2013

Inday Goes About Her Day

Locsin Books, 2012

Beautiful Accidents: Stories

University of the Philippines Press, 2011

Heartbreak & Magic: Stories of Fantasy and Horror

Anvil, 2011

Old Movies and Other Stories

National Commission for Culture

and the Arts, 2006

FutureShock Prose: An Anthology of Young Writers and New Literatures

Sands and Coral, 2003

Nominated for Best Anthology

2004 National Book Awards

3:14 AM |

On Edward Hopper

3:14 AM |

On Edward Hopper

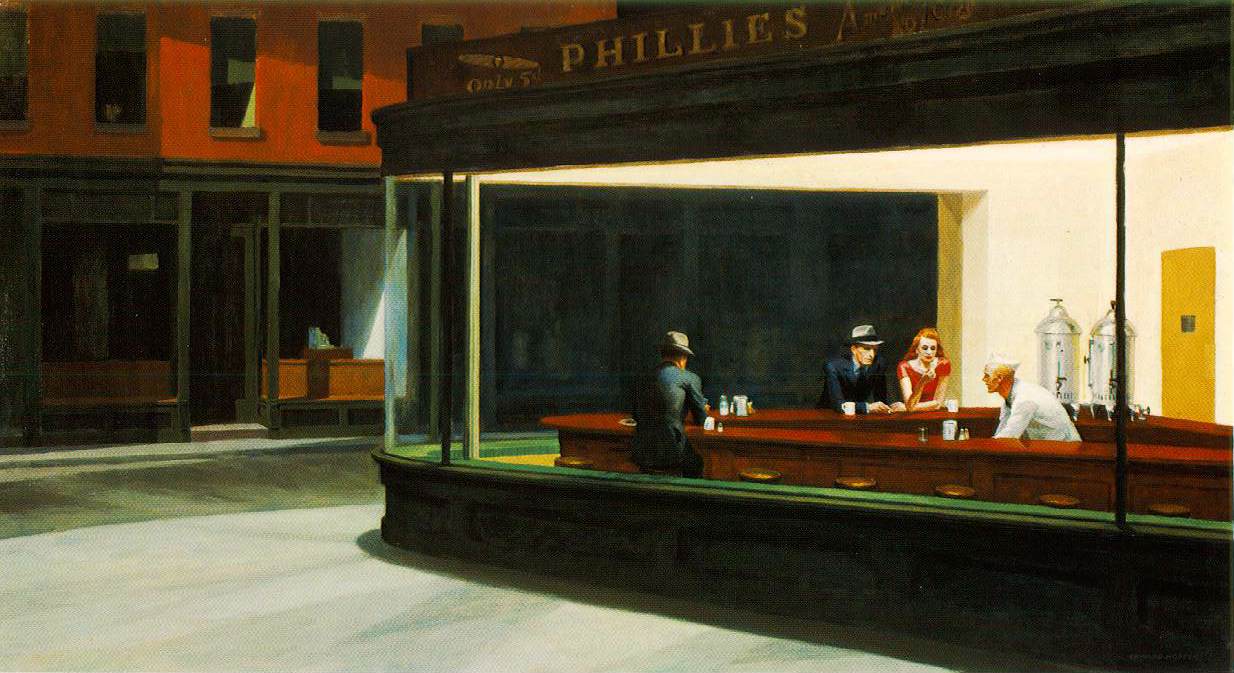

Apparently, there was a period when every college dormitory in the country had on its walls a poster of Hopper's Nighthawks; it had become an icon. It is easy to understand its appeal. This is not just an image of big-city loneliness, but of existential loneliness: the sense that we have (perhaps overwhelmingly in late adolescence) of being on our own in the human condition. When we look at that dark New York street, we would expect the fluorescent-lit cafe to be welcoming, but it is not. There is no way to enter it, no door. The extreme brightness means that the people inside are held, exposed and vulnerable. They hunch their shoulders defensively. Hopper did not actually observe them, because he used himself as a model for both the seated men, as if he perceived men in this situation as clones. He modeled the woman, as he did all of his female characters, on his wife Jo. He was a difficult man, and Jo was far more emotionally involved with him than he with her; one of her methods of keeping him with her was to insist that only she would be his model.

From Jo's diaries we learn that Hopper described this work as a painting of "three characters." The man behind the counter, though imprisoned in the triangle, is in fact free. He has a job, a home, he can come and go; he can look at the customers with a half-smile. It is the customers who are the nighthawks. Nighthawks are predators -- but are the men there to prey on the woman, or has she come in to prey on the men? To my mind, the man and woman are a couple, as the position of their hands suggests, but they are a couple so lost in misery that they cannot communicate; they have nothing to give each other. I see the nighthawks of the picture not so much as birds of prey, but simply as birds: great winged creatures that should be free in the sky, but instead are shut in, dazed and miserable, with their heads constantly banging against the glass of the world's callousness. In his Last Poems, A. E. Housman (1859-1936) speaks of being "a stranger and afraid/In a world I never made." That was what Hopper felt -- and what he conveys so bitterly.