Saturday, November 29, 2008

9:52 AM |

Dumaguete, Light and Dark

9:52 AM |

Dumaguete, Light and Dark

There is truth to that cliché, “Beauty is in the eye of the beholder.” What we see is governed (or at least informed) by the relative. That is to say, perspective is slave, always, to context. What you see is

always something you have been

led to see.

You can throw bricks and stones at me right now for sounding positively academic. (I can’t help it. I’m a teacher.) But let me give you an interesting proposition: there is an apocryphal story that contends that when Christopher Columbus first sailed to the Americas, the Native Indians could not see the ships hurtling towards shore because they simply had no concept of what a “ship” was, and thus could not see it, even when it was right in front of them. Of course, this story is much debated and borders in legend. But it does make us think: do the things that we see actually exist? Or can our brains play tricks on us sometimes?

This is a strange beginning for an article about Dumaguete in the photography of John Stevenson and Hersley-Ven Casero, but bear with me.

I first understood this concept of “tricky perspective” when I began taking photography as a college hobby. I was young, and found myself suddenly trying to become familiar with the visual grammar of Richard Avedon, Bruce Webber, Ian Bradshaw, Robert Mapplethorpe, Diane Arbus, Man Ray, Vittorio Sella, Gary Winogrand, Frederick Sommer, Jerry Uelsmann, Edward Weston, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Louis Faurer, and many others like them. These were the Greats: men and women who took photography from the hands of enthusiastic amateurs and turned it into art.

Photography is the most democratic of all the arts. The camera is a ubiquitous object (there’s one in your cellphone right now) and just about anybody can click a shutter. It’s not hard. But the thing that separated the Greats from the rest of the click-happy majority was the concept of the “photographic eye”—that strange ability to capture real life moments in arresting artistry (which is called “composition”), and governed by a vocabulary that shares the same aesthetics as painting. Unlike painting, however, photography had the added conceit of the “real,” thus rendering it with a power to consume our attention that is surpassed only in modern art by cinema.

But let me go back to my college days. There were days on end when I would go around the streets of Dumaguete City snapping pictures of everything—children playing in the streets, vendors hawking their wares, people strolling the Boulevard, women in

dasters going about their daily

tsiangge haggle. When there were big events that called for parades, I would take pictures of the swirling dresses, the colorful floats, the abundant smiles.

The Dumaguete captured by my camera’s lenses was a colorful city informed by the language of travel magazines and brochures. This very fact did not bother me at all, and I never even thought hard about the innate perspective that went subconsciously into my compositions. Everybody else I knew who photographed Dumaguete seemed to capture the place in exactly the same manner. Swirly. Sweet. Smily. Full of balloons. Which is not bad—but I have since come to suspect the context with which I take photographs of my city. I am perhaps informed by the native tendency to show one’s place in the sunniest of disposition, the way we clean our houses in anticipation of visitors. Was this the real Dumaguete I’m taking pictures of? Or something subconsciously fabricated or staged-managed?

I ask these questions because the first time I saw the Dumaguete photographs of Mr. Stevenson, I was struck by a completely different pictorial story. His pictures seem to come out from a certain netherworld, something at once familiar and strange: his is a Dumaguete rendered in the starkness of film noir, always with a hint of dark mystery or something sinister to them. I don’t see this Dumaguete at all with my own eyes, but nevertheless my gut tells me that Mr. Stevenson’s pictures are truthful, too. They are, in fact, the perfect foil to our tourist-brochure perspective, something that colors the photography of Mr. Casero, especially his early photography. Combined, Mr. Stevenson’s pictures and Mr. Casero’s (and ours) become the all-encompassing portrait of our city: Dumaguete in dark and light.

I have known Mr. Stevenson for about eight years now, and Mr. Casero a little less than that. I first knew of Mr. Casero when he was drawing editorial cartoons for MetroPost, and made what is probably the most fantastic (and highly observant) caricature of me as a columnist for that paper. I was impressed. I first met Mr. Stevenson when a common friend noted our shared fascination for old films and for photography. That both work together now under the same department in Foundation University seems divinely connected to me since I see their works as perfect composites of the visions and revisions of Dumaguete. They’ve had exhibitions together before, notably in their parent university—and it is only fitting that both their visions of Dumaguete can be shared to the greater community through an exhibit titled “Dumaguete Light and Dark,” sponsored by the Silliman University Cultural Affairs Committee, and running till the end of November at the Main Exhibition Hall of the Robert and Metta Silliman Library.

That the exhibit coincides with the Dumaguete fiesta is by design: it helps celebrate the city’s charter day by showing a profile of Dumaguete as it has never been seen before.

Besides his photography, Mr. Stevenson is also a writer and filmmaker, an American who has chosen to reside—sometimes to his own bewilderment—in Dumaguete for the last ten years. He first became interested in photography as an artistic medium at the age of twelve. Born in 1942 in Berkeley, California, he is the only son of David L. Stevenson, a well-known scholar of Elizabethan and contemporary literature. Being Dumaguete-bound was probably farthest from his mind growing up. He was educated at, among other places, Windsor Mountain School (in Lenox, Massachusetts), Westminster School (in London), and Western Reserve University (in Cleveland Ohio), where he majored in English literature and philosophy. It was an education that was designed to lead him, like his father before him, to a conventional academic career. He decided to buck that by briefly studying film production at CUNY Film School in New York City. He soon entered the work force in search of a career in film and photography, which led him to San Francisco. It was love (and assorted friendships), however, that led him to the Philippines.

There was a time when I would trekked to Mr. Stevenson’s old house somewhere near Bacong Beach where we would view and discuss old black-and-white films, mostly film noirs, such as Billy Wilder’s

Double Indemnity, John Huston’s

The Maltese Falcon and

The Asphalt Jungle, Orson Welles’

Touch of Evil, Alfred Hitchcock’s

Psycho, Sidney Lumet’s

The Pawnbroker. That was instructive for me to understand where he came from and what informed his aesthetics. For the uninitiated, film noir is a cinematic term that describes stylish Hollywood crime dramas—which emphasize moral ambiguity and sexual motivation—and chief among its styles is low-key black and white cinematography, signaling the symbolic contrasts that govern our lives. That is what you exactly get in his photography—a Dumaguete in black and white, populated with people whose faces become unwitting battlegrounds for the dilemmas and ambiguities within.

Mr. Stevenson hesitates to title his works, which only adds to the whole “ambiguous” theme of his pictures, but there is one photograph that works best to capture what he is trying to say. It is a black-and-white scene of a Dumaguete fiesta, and people are milling about the Boulevard. On one side is the sea, with the city’s lights reflected on the dark waters. On the other side are booths to house the assorted eating places who have temporarily set up shop along the city’s grassy and tourist-friendly promenade. In the middle are various men walking about. Some are seated on a stage set up in the middle of the brick walk. Two men—one in a white shirt and the other in something with flowered prints—are distinct in the foreground. They are in the midst of so much celebration—and yet, there on their faces are faces of total boredom or total blankness.

The first time I saw this picture many years ago, I exclaimed: “

That’s Dumaguete!” I still cannot explain what made me exclaim so, but the ambiguity felt real: Dumaguete is ambiguous, a city of such renowned “gentility”—but the most discerning among us often confess to seeing or feeling a darkness that lies within that generosity of soul.

Mr. Stevenson has another shot of the Boulevard that tries to be clearer about this duality, or ambiguity. It is a shot of the pier, right where the Boulevard turns a corner towards where the ships are.

The cemented embankment that separates Tañon Strait and the streets of the city divides the picture perfectly: to the right, the rolling sea—wavy, but monotonous in its grey expanse; and to the left, Dumaguete’s streets garbled by parked motorcabs and street signs—unmoving, but teeming with such bottled energy.

A triptych, all set in the Boulevard, involving a single wooden stand selling some sort of merchandise (for P5.50) with Tañon Street as a backdrop, is also emblematic about the city Mr. Stevenson tries to chronicle. The wooden stand occupies the middle of all three photographs. In one, a woman and child enters the frame from the left, and regards the stand with an uninterested stare. In another, the wooden stand occupies the frame all by itself, with only the seawaves for company. In the last photograph, a man sits at the background, looking quite introspective, his hand cupping his head. The blur of an incoming motorcycle enters the frame from the right. And still the waves roll on, and the stand remains immobile. “

That’s Dumaguete!” I exclaimed once again. A Dumaguete where nothing—and everything—seems to happen, where the rolling sea is the only constant (there goes your paradox), and a rickety wooden box becomes symbolic of the immobility that afflicts most of us in this sad, contented city.

Mr. Stevenson has other photographs, of course, all of them detailing his recurring theme: shoppers outside Lee Plaza milling about with vacant faces, a frowning man looking at a gas pump, people sitting in the shadows of the Boulevard at night with Christmas

parols the only illumination they have, a boy staring impassively out of his humble house’s veranda, a uniformed schoolgirl pausing dramatically by the seawall.

They add up. Mr. Stevenson, informed by his love of film noir and by his outsider/foreigner status in Dumaguete, shows a city that is irrepressibly social, but also sad, teeming with people but also of loneliness. Like any artist grappling with their muse, he does not deliberately set out to render Dumaguete so: “The idea is to use a camera to seize moments in time, moments that seem to capture the spirit and feeling of the world around you in a powerful and dramatic way,” he says. “I was excited by the idea of doing this kind of photography in Dumaguete because, unlike places which have been pictured a million times by everybody, no one had ever worked in this style here, so I had virgin territory in front of me. Although these photographs form a kind of picture of Dumaguete and its people, they have no message. When I took them, I had no particular theme in mind, nor did I intend any judgment on what I saw. They reflect only my instinct to shoot at that particular moment.”

That may be, but we can alter a bit the cliché that begins this article, and say, “The message is in the eye of the beholder.” We see his photographs, and a kind of pattern emerges, and it carries a message whether he likes it or not. It is, of course, also a “message” that is substantially helped by the peculiarity of his style. Mr. Stevenson acknowledges this: “Photographs have a life of their own, in spite of the photographer’s intentions. I am often amazed to find that a finished picture has a completely different feeling than I imagined it would have when I took it—sometimes for the better, often for the worse. So it’s not fair for me to take too much credit for the result in any particular case, no matter how good it might seem. I’m just happy that so much turned out so well.”

And what is often the result? A picture of Dumaguete’s dark and pulsing heart—and I appreciate that as a good, complimentary contrast to our own overwhelming tendency to focus on the bright, brochuristic, and facile sides of our city.

We can say that Mr. Casero is of that brochuric bent—his pictures are full of color, of smiles, of laughter, of costumes, of bright sunsets—but I sense that his pictures have a subversive heart that popular photography often lacks. Still, this is incredible for a photographer who only took to the lens quite recently. Though a recipient of the annual Artist Award given by his alma mater Foundation University, Mr. Casero—it bears mentioning—is a marketing graduate. Which may be why the tilt of most of his early works tended towards a “photographic marketability” of Dumaguete. His well-received efforts have an assuredly mass appeal, and his various awards and achievements show that: he is a finalist of the Philippine Airlines Photo Contest, a finalist of the Water is Life Photo Contest, and champion of the 2006 Buglasan Photo Contest. His works have also been featured in various photography websites, and he has published both nationally and internationally.

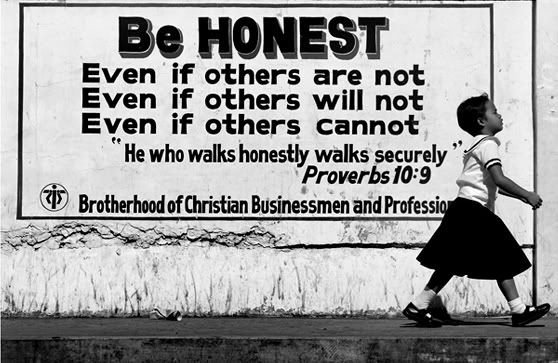

Mr. Casero’s work is a stark contrast to Mr. Stevenson’s, even if many of his latest works now come in black and white—something, he says, he got from the latter. Looking at their works, I can say both have slightly influenced the other. But not so much. Consider the leaping trio of boys in the beach during sunset in Mr. Casero’s collection. Consider the stomping figure of a little girl in school uniform walking past a banner that reads “Be Honest.” Consider the splashy photo of a boy laughing and playing in the surf. Consider the low-angle shot of milling people (one of them in a wheelchair) gathered around one of the Boulevard’s distinctive ornate streetlamps, with the sky swirling with clouds in the background. Consider the seated boy flanked by huge advertising tarpaulins showing a laughing baby happy with Pampers diapers. Consider the boy leaping with joy as his kite escapes flying to the air. Consider the close-up of a boy whose small face is the tight shot for this exercise—but look at the sparkly depth of his eyes. Mr. Casero’s color photographs are even lovelier in their cozy comforts: a trio of children sitting on a makeshift swing, the shadows of five kids in a playground as they swing towards a sunset, a quartet of kids scrambling up a tree, two girls picking seashells in the sunrise, a figure of a boy framed by a dark foreground of sand and a bright background of silver clouds and spilling sunshine, a wide-angle shot of a parked bicycle that seems to hurtle towards a sitting boy…

Even a shot of a young girl picking through garbage in a landfill seems surprisingly sweet. Or at least romanticized.

And yet the sweetness of his photographs—all populated by children—does not lend a diabetic bent to them. They lack the grainy and direct sadness of Mr. Stevenson’s photographs, but they nevertheless share that theme of ambiguity. Because although Mr. Casero’s work may seem perfect for another generic issue of a travel magazine, they are surprisingly informed by a certain gravity. This gravity is an apparent acknowledgement that there is “something else” behind these children’s smiles and their antics. That “something else” borders the region of photojournalism and its penchant for social messages. Here, that message is given to us in a very subtle manner. Mr. Casero’s pictures make us feel delight in his stock images of happy children, but we are left with a nagging doubt at the back of our heads that something is completely off. And so we begin examining even further his photos—and we discover an entirely new world: that of happiness in desperation’s robes. In that sense, Mr. Casero’s photographs may be the most subversive in the whole exhibit.

I actually conceptualized this exhibit many years ago, and this year, the CAC has finally made this vision alive. This month we are celebrating the fiesta of Dumaguete City, and what other brilliant way can we give tribute to the City of Gentle People except through these glimpses through photography.

I will end with this question: which is the real Dumaguete? It’s all in the eye of the beholder. We all create our own sense of place, perhaps informed by where we come from.

Labels: art and culture, cultural affairs committee, dumaguete, exhibits, negros, photography, silliman

[0] This is Where You Bite the Sandwich

GO TO OLDER POSTS

GO TO NEWER POSTS

9:52 AM |

Dumaguete, Light and Dark

9:52 AM |

Dumaguete, Light and Dark