Friday, October 09, 2009

4:38 PM |

The Long Party of the Bubble Years

4:38 PM |

The Long Party of the Bubble Years

Part 3 of a Series on Night Life in DumagueteRead Part 1 |

Read Part 2“We were gods and goddesses of dance and light. Everywhere we went, we glittered.”

—ERIC SAMUEL JOVEN,

on Dumaguete of the mid-1990sAll

what ifs, given the right nurturing and a little kick of imagination, are excuses to party.

Like all good ideas that become infectious and are soon carried through by the sheer push of will and word-of-mouth, the one I am about to tell you started out as a broad stroke of such kind of speculation.

But let us begin by noting that

What Ifs was the game to play—bordering sometimes on the wicked and the suggestive—in the boredom-infested, pre-cellphone, pre-Facebook days of the mid-1990s. This was when, for a brief moment, a kind of affluent flowering enveloped a suddenly burgeoning Dumaguete, turning the city into a frenetic beehive.

It was a brilliant bubble of a time, coming right before the Asian financial crisis (which shook our lives, and from which we have yet to recover). President Fidel Ramos was in power, and the Philippines—just coming out of the dark ages early in the decade that saw the country crippled by endless blackouts that ravaged the economy—was suddenly enjoying a belated (and, alas, short-lived) reputation of having become the new economic miracle of the region, Asia’s “new tiger.”

Those were the days when Dumaguete began stirring from the slumbering pace, when old and new began to clash and to accommodate each other. Its narrow streets were no longer so quiet. By 1998, Felipe Antonio Remollo was the new and dynamic mayor. Everybody suddenly seemed flushed with extra cash. The air was drunk with unbridled optimism (there was talk of a Metro Dumaguete, of urban master plans that would change the way Dumagueteños lived and interacted…). Every day felt like a promise of bigger things. And every night was a party.

There was no such thing as a slow night at the Rizal Boulevard, for example. In the heady days of the 1990s, it was Party Central every night of the week—even Sundays. Newly rehabilitated from its bleak 1980s reputation as a red light district, the seaside promenade was suddenly a slick stretch of simple but handsome design, thanks to outgoing mayor Agustin Perdices. The place practically leaped away from its previous incarnation as a concrete monstrosity with bad lighting. Suddenly, it became postcard perfect. There was now a set of faux-antique lampposts lining the walkway, as well as a meticulously cultivated landscape of carabao grass with brick (and later, brown slate) borders. Families could picnic in the new Boulevard in the daytime, and nocturnal creatures could cruise a thriving scene after hours, drinks permitted.

The famed Sugar Houses along the Boulevard stretch, long “abandoned” by their

hacendero owners to the ravages of time and fortune and the red blinking lights of streetwalkers, were suddenly being spruced up. Tocino Country—the collective name of the mass of barbecue stands that dotted the Boulevard—was transferred to the vacant lot fronting West City Elementary School, where it thrived for years. (Now it is situated on the lot beside the City Engineer’s Office in Lo-oc.) New restaurants were opening along the stretch, and new hotels, too. Bethel Guest House, the Cang family’s idea of a “Christian” hotel, was a swanky addition to the Boulevard cityscape—and Honeycomb followed suit, settling in the old Medina mansion, which was refurbished to suit its new function. The Lees, too, took over the old house where the legendary local mystic Father Tropa used to house his exotic pets, and made it into a slick bar called Lighthouse. This became the nightly hub of the young social set. (This is now Shakey’s.)

Over at the other end of the stretch, near Silliman University, some things strained to get on with the bandwagon—like Ocean’s Eleven across old Silliman Hall. (This is now Blue Monkey Grill). The restaurant didn’t quite catch on, and for years, the place was reduced to a rubble of an empty lot. But, near it, Hotel Al Mar suddenly became a more posh La Residencia; across the street, the honky-tonkish building housing a pub called The Office became a private condominium where Globelines now is; and the barely-used lot beside The Office became an outdoor grill and beer garden called Ang Boulevard. Much later, that beer garden became a popular bar done up in a ‘50s diner-style and was called, appropriately, Happy Days. (This soon became the short-lived Grin Life, and is now CocoAmigos.)

Happy Days… This was where Tina Alcuaz, the proprietress of exceeding proportions (a cheerful demeanor included), reigned over the black and white chessboard-tiled floor, flanked by screaming red walls with framed posters of Marilyn Monroe, Frank Sinatra, Elvis Presley, and the whole pantheon of classic Hollywood icons... This was where her friend Zaldy would tether his horse outside, after a gallop at the Boulevard.

(Yes, a horse...) This was where the A and B Crowd descended regularly for their fix of Budweiser, then the beer of choice. In the island bar that dominated the middle, a kind of social Mount Olympus existed. On one end, Vincent Joey Alar—the 1990s poster boy for partying—trafficked the crowd, introducing everybody to everybody else. “Gideon of Caballes Printing Press,” he would say, for example, “this is Star of Wuthering Heights. Say hi to each other.” The placed buzzed with

beso-besos everywhere... Every night was dance night. This was where Wednesdays happened, before there was ever a Reggae Wednesday in Hayahay... This was where we held plenty of erotic poetry readings—courtesy of the shenanigans of the posse of the resident intellectuals Eva Repollo, Jean Claire Dy, Bombee Dionaldo, Jesselle Baylon, Tintin Ongpin, and Aivy Nicolas—complete with smoke machines, a ceiling full of condom balloons, and throaty deliveries and a lot of moaning... This was where Tuesday Nights were Girls Nights, Thursday Nights were (unofficially) Gay Nights, and the rest of the weekend a merry mix of Everybody Else.

Those days, indeed, were happy.

It suddenly seemed that Dumaguete was becoming truer to its cityhood. It was starting to

feel like one; it was no longer so much an overgrown town, although much of its charm was still derived from a lingering sense of smallness as well.

It became a kind of secret destination, a Filipino city that was like no other. Soon, celebrities—film and TV actors and singers of all stripes—were constantly flying in from Manila, not to perform, but to bask in the Dumaguete sunlight as adopted locals. Here, they could not be harassed as they would be in Manila’s public places. They could walk the main stretch of Alfonso Trese (which was renamed Perdices Street), and not be gawked or rushed at by hysterical fans.

Then again, it was an old Dumaguete (now gone) that didn’t care much about local celebrities, nor fawned over them. It was a city that was not capable of being star-struck. (The teleseryes of ABS-CBN and GMA had yet to come in with such popularity to make a

bakya masa of all of us.)

It was a city where actors like Mark Gil could come in to set up shop. In the old Perdices mansion along the Boulevard, where Mamia’s is now, the actor opened Limelight—a grand forerunner of El Camino Blanco,

only better—which was a fine dining restaurant by day (and all throughout dinnertime) and a VIP club by night. This was where the best parties happened—its kidney-shape bar overflowing with the partying days of Daniel Fernandez, who was Dumaguete's Party King and Ultimate Ringleader.

And the city, of course, felt like partying with him. It partied for the rest of that decade, to the soundtrack of Paul Van Dyk, Alanis Morisette’s

Jagged Little Pill and Madonna’s

Ray of Light.

“In 1996,” now Manila-based Dr. Gideon Caballes recalled, “the place to hang out in was El Amigo, our version of Minimik. It had great food, cheap too, but it was generally a nice place to chat over beer. And I remember Orient Garden, fronting what is now Gold Label Bakeshop. It was around from 1987 until probably 1990. It had a band famous for overplaying ‘The Name Game’ song. I remember hanging out at St. Moritz in Agan-an a lot. It was a nice seaside place to have a cheap date. This was the place to go to before Escaño became popular. Then there was Colors Disco in front of West City Elementary School. Then there was Music Box and that disco on the second floor of Gemini Building around 1991 or 1992. In 1996, there was Gimmick. Remember when Warren Cimafranca first broached the idea of opening an outdoors bar in the family property in the middle of all those residences in Claytown? We all told him the idea won’t work. That it would flop. We ate crow later on, didn’t we? We had no idea it would become so successful. Is it still the place to be seen in right now?”

The long party would go on until a little beyond the worldwide welcome for the new millennium (which unleashed the biggest Boulevard party in local history—complete with fireworks and spontaneous dancing in the streets).

The party would go on into the frenetic months of the Silliman Centennial, culminating in August 2001 when—for an entire month—Dumaguete did not sleep. That August was the peak of Dumaguete’s partying: it was filled with

hundreds of random 24-hour parties

everywhere, lasting all of its 31 days. How busy was it? Imagine the ultimate in traffic gridlock—at four o’clock in the morning, every day.

Then September 11 happened. When we all lost our innocence that day, our world shattered and shaken, the party ground down to a halt. For the next five years or so, all we had were shadows and memories.

Every generation in Dumaguete’s social set always has a muse who sets the tone for the party scene of the moment—a list that would include Jacqueline Veloso, Lua Khanum Padilla, and Christine Torres.

Flashback to 1996. Campus beauty Cherokee Dawn Esguerra—known more affectionately as C.D.—decided that she wanted to remember her twenty-first birthday the best way possible and in a manner that staid Dumaguete had never seen before. She was then the reigning Miss Silliman, and she would have none of the usual birthday buffets. None of the usual

inuman at St. Moritz either. And none of the usual beach parties in the Bais sandbar, or Dauin. The speculation she hatched that soon raced through town like wildfire and had every one clamoring for the “exclusive” invitation to the shindig was—

what if she invited the Who’s Who of the young Dumaguete set and ask them to dress up in 70s vintage costume, would they come?A costume party. In the bell-bottomed, tie-dyed, sideburned, miniskirted gloriousness of the Bee Gees and their 1970s ilk.

The idea worked, for the most part, because of the promise of exclusivity.

You were either invited, or you were not. For days before the party, those who still did not get the purple envelope with instructions to descend in full vintage regalia on the Joshua Room of Bethel Guest House—then the newest hotel in town—were feverish from anticipation and worry. It became, so to speak, a question of sociable existentialism:

if you did not get the invitation, were you in fact a nobody?In retrospect, the theme of the party was perched on an idea of risky novelty, given the notorious tendency of many Dumaguteños to spoil the fun in the name of “keeping a low and humble profile.” This is often the excuse for dressing down and going around in typical

pambalay wear—a plain shirt (several sizes loose), a pair of “city shorts,” and sandals or espadrilles. Even for parties. And yet, perhaps for the first time ever, people heeded the sartorial challenge and began digging into their parents’

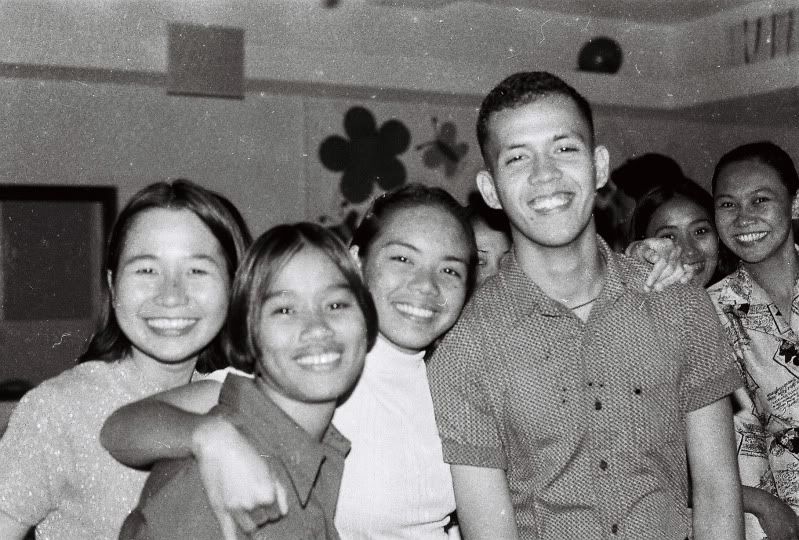

kabans. I went in as Elvis Presley in his Las Vegas years, minus the drugs and the paunch and the air of eventual doom. My pair of bell-bottoms was hot purple, my shirt a blazing LSD rainbow in brilliant Technicolor. My hair was too short, however, to be coifed into the standard Presley style—but I promptly made do by sporting fake sideburns. Everybody else—save for a staggering few who came in dressed as typical Dumaguete killjoys—dressed to the nines, and came in droves to the Boulevard, down to Bethel. They became a spectacle the likes of which this small city has never seen before. Everybody danced to the merry hits of the Village People and the Bee Gees and Gloria Gaynor until the wee hours, and soon everybody spread out around the city to satellite social hubs—the neighboring Lighthouse Bar was the next best thing—to prolong the party.

And for the longest time, that 1970s shindig was billed as the ultimate Dumaguete party to beat. It took five more years—with the month-long centennial celebration of Silliman last 2001—and another eight years—with the Philip Morris party last August—before the sheer audacity of C.D.’s party could be eclipsed. Great parties in Dumaguete, we soon learned, always came far between.

But in the final analysis, the 1990s would forever be marked as the decade where the city flowered and changed. Variety bloomed, for one thing. “In my time,” artist Sharon Dadang-Rafols said, “it was Silliman beach and Wuthering Heights, and it was always ‘action’ with friends,

inom, tsika, poetry readings...”

“The places we went to,” recalled Silliman University’s students activity head Jojo Antonio, “were Lighthouse and Gimmick. In Lighthouse, new bands played every two to three weeks, and they were all from Manila and Cebu. The music ranged from the usual latest pop hits to retro. Everybody knew everybody then, and one didn’t worry over getting stabbed and shot after the late night fun. We could even leave our rhum or tequila bottles in the bar with our names scribbled on them, ready for consumption for the next day’s hangout.”

“Limelight was the ultimate!” remembered medical representative Jesselle Baylon. “It was great because of its cool house music. Great service, too. And in Lighthouse, we got different bands from all over the country, every month. And for your last stop if you felt like partying at 2 AM onwards, there was Detour. I

loved that placed. It was hard to get another drink, and you just stand the entire time because there were no chairs—but people danced like crazy and you couldn’t help but bust your own moves… Dumaguete party places back then were better—but the number of people who knew how to party was even less than we have now. Now you have cross-generations of partygoers from their teens, their 20s and 30s. I wonder why they don’t open any more bars or clubs…”

To be continued…Labels: dumaguete, history, life, memories, negros, party, silliman

[0] This is Where You Bite the Sandwich

GO TO OLDER POSTS

GO TO NEWER POSTS

4:38 PM |

The Long Party of the Bubble Years

4:38 PM |

The Long Party of the Bubble Years