Wednesday, July 14, 2010

2:04 PM |

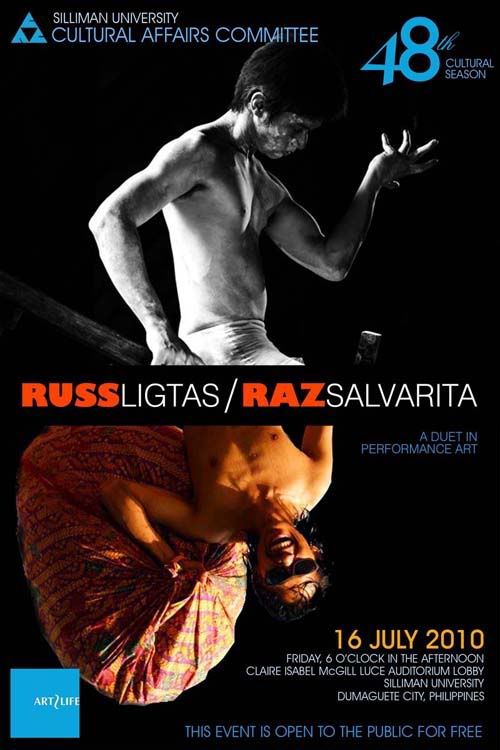

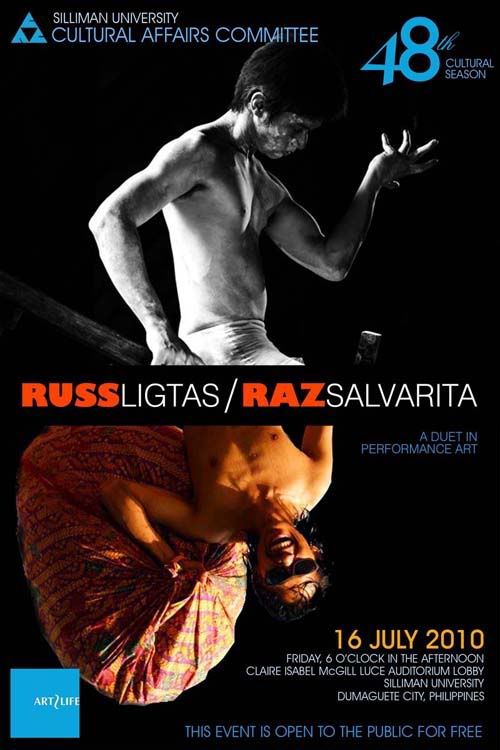

A Duet in Body and Imagination

2:04 PM |

A Duet in Body and Imagination

I have a love-hate relationship with performance art. When it’s good, it blows our minds and makes us reach deep within ourselves, asking questions about this and that. It transcends its inherent strangeness—

and all performance art is strange—and makes the familiar both unfamiliar and intimate at the same time.

But when it’s bad, you feel like a monkey’s uncle.

Once in Hayahay I had to sit through a turgid piece by some performance artist from Manila, whose work consisted of reading aloud to the microphone entries from the Webster’s Dictionary. It’s not that I didn’t get it: it was just a bad piece, a complete waste of time—and like the worst of junk art, it didn’t give us anything new. “If I wanted to get the definition of the word ‘ghastly,’ I’d be home and find my own dictionary,” I told my companion. “I didn’t have to come here all the way through the rain, with an order of beer.”

But all performance art always courts the tricky borders of ghastliness and transcendence. Some do it though with the command of the true artist. I know the writer Vim Nadera does his performances with much wit and aplomb. In Dumaguete, there is Tara Ilic whose feminist moanings are designed to make the hair at the back of your neck stand.

There have been a lot of performance artists whose place in the world of art is now part of history: Yves Klein, Japan’s Gutai Group, Joseph Beuys, Allan Kaprow, and the controversial Carolee Schneemann. They all have put their distinct signatures to the art form—which is an inevitability—but all subscribe to the general definition, here provided by Wikipedia, of the art “in which the actions of an individual, or a group at a particular place and in a particular time constitute the work, and can happen anywhere, at any time, or for any length of time, involving any situation that involves four basic elements: time, space, the performer’s body, and a relationship between performer and audience.”

Let me give a popular example. In 1975, the great performance artist Chris Burden unveiled one of his most well-known works, in

Doomed, in which he lay motionless in a gallery at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago. He was under a slanted sheet of glass with a clock running nearby.

The hours passed. People were beginning to be worried—Mr. Burden had not had any food or water or any break to relieve himself. What the museum administrators did not quiet know was that Mr. Burden hatched the idea for the piece that he would remain, “doomed,” in that position until someone or something would interfere in some way.

The film critic Roger Ebert writes of that event, where he quotes museum curator Alene Valkanas:

’The piece ended at 5:20,' she said. Forty-five hours. 'We felt a moral obligation not to interfere with Burden’s intentions, but we felt we couldn’t stand by and allow him to do serious physical harm to himself. There was a possibility he was in such a deep trance that he didn’t have control over his will. We decided to place a pitcher of water next to his head and see if he would drink from it. The moment we put the water down, Chris got up, walked into the next room, returned with a hammer and a sealed envelope, and smashed the clock, stopping it.’

The envelope contained Burden’s explanation of the piece. It consisted, he had written, of three elements: the clock, the glass, and himself. The piece would continue, he said, until the museum staff acted on one of the three elements. By providing the pitcher of water, they had done so.

‘I was prepared to lie in this position indefinitely,’ he wrote. ‘The responsibility for ending the piece rested with the museum staff but they were always unaware of this crucial aspect’...

‘My God,’ Valkanas said. ‘All we had to do was end it ourselves, and we thought the rules of the piece required us to do nothing.’

Read more here.

It blows the mind. But while performance art has become a mainstay in the world of art in general, in terms of popular acceptance and visibility, it still has to take its roots in the culture of Dumaguete. In that sense, the city is “ripe” for a good introduction into the best of local performance art, with Russ Raniel Ligtas of Cebu City and Razceljan Salvarita of Bacolod City and Dumaguete.

Mr. Ligtas is a visual and performance artist who regularly performs with Cebu’s only performance art group XO?. His performances involve dance, costuming, and pop culture elements. He writes poetry and other creative text and is a member of the Cebuano writer’s group Bathalad Inc.

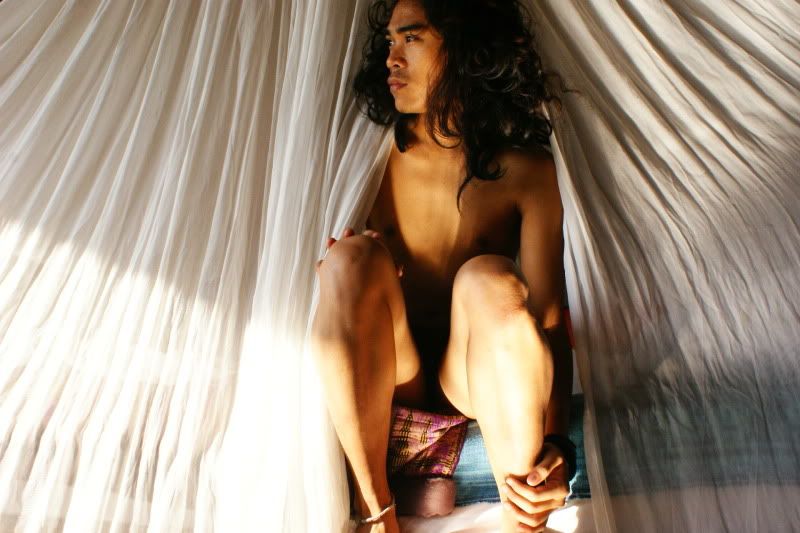

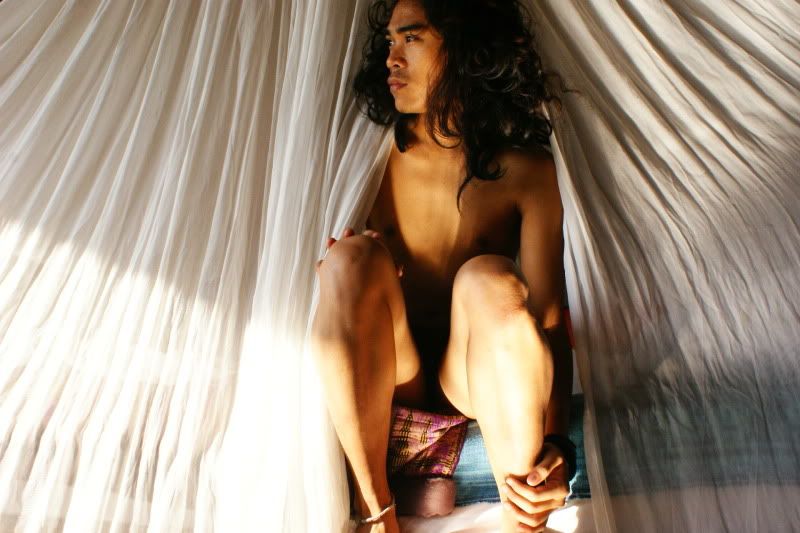

Mr. Salvarita, on the other hand, is a member of a family of artists based in Bacolod, but is now based in Dumaguete City and Bali, Indonesia. He graduated with a bachelor’s degree in Mass Communication at Silliman University, where he also later pursued a master’s degree in Environmental Policy. Razcel, perhaps Dumaguete’s fast-rising young visual artist is also a writer, a photographer, a performance artist, an environmental activist. He is best remembered as the person whose body was painted white and then who walked around Dumaguete semi-naked to call attention to his “Save the Balinsasayao Twin Lakes” campaign. He has also founded the collective art group Artantrum.

On

16 July 2010, each one will present a suite of three performances, alternating with each other. The combined work, titled

Russ/Raz: A Duet in Performance Art, is sponsored by the Silliman University Cultural Affairs Committee, and will be performed at the Claire Isabel McGill Luce Auditorium Lobby at 6:00 PM.

It is open to the public, and they are prepared to blow our minds with this duet of strangeness involving body and time and space and us, the spectators.

Labels: art and culture, cultural affairs committee, dumaguete, negros, performance art, silliman

[2] This is Where You Bite the Sandwich

GO TO OLDER POSTS

GO TO NEWER POSTS

2:04 PM |

A Duet in Body and Imagination

2:04 PM |

A Duet in Body and Imagination