Saturday, October 17, 2009

7:37 PM |

Negros Through the Personal

7:37 PM |

Negros Through the Personal

The art of photographing places can be tricky. Given the ubiquity of the camera in these digital times, a lesser photographer, especially those ignorant of the whole photographic tradition (

Ansel Adams and Henri Cartier Bresson who?), can always be reduced to romanticizing the generic—another shot of distant mountains, another shot of a bustling downtown, another shot of an orange sunset or sunrise—and think they are God's gift to the whole art.

Generic.The results, of course, may be sufficiently arresting in their capture of a beautiful landscape, but in the relentless democracy of images we find ourselves awash in, the trick for the photographer who is also a true artist is to have something to say, and to say it in composition that awes. This is often difficult because much of photography relies on extinct gained from experience and the luck of having clicked the shutter at the right dramatic moment. But all these still come together because of the artist’s personal vision.

Good photography is all about the visual story. Which is why there is much to rejoice—and also perhaps to shrug off—over the ongoing photography exhibit at the Sidlakan Negros Art Gallery.

Dubbed

My Negros Oriental, the exhibit—which extends through the entire Buglasan Festival run until October 26—gathers for the first time fifteen photographers from all over the province, each one tasked to capture what for them is a very personal vision of Negros Oriental. All told, these are unique stories of the place set in the eye (or the camera) of the beholder. That personal and individual focus (we actually see the personalities of the photographer) is why much of the collection succeeds, because the exhibit indeed manages to transcend, at least for the most part, the commonplace.

Still, some of the exhibitors such as

Gerald dela Cerna, Revey Nuico, and

Randolf Bandiola feel restrained from going beyond the box. What we mostly get are generic beauty shots—I call them “the postcard factory for brochure tourism.”

In Mr. Bandiola's case, his shots of the oldest tree in Canlaon, the caves of Mabinay, the mountain rivers of Valencia, the architectural odds and ends of Bayawan are perfect examples, but in “Dagitab sa Sanga,” a serene portrait of a gas lamp shining bright against the encroaching darkness, we get a

tad of a promise of something else. That can grow, and as we say in cases like this, Mr. Bandiola is a photographer to watch.

Alma Zosan Alcoran

Alma Zosan Alcoran’s photographs are set in the tradition of the matter-of-fact—unembellished images that may lack the punch of depth and contrast, but nevertheless successful because they manage to put out the drama of the unexpected. There’s the sudden bird over a sailing boat in “Means of Transportation.” There’s the ball of fire coming to sharp focus after a swirl in “Kisaw.” There’s the almost surreal burst of color against night skies in “Buglasan Fireworks.” There’s the seemingly sudden gesture of a peace sign from two girls in costume in “We’re Friends.” There’s the Philippine Airlines plane descending over cranes in the pier in “Untitled.”

Jaysie Tayko

Jaysie Tayko, on the other hand, has perhaps the photographs that are most interestingly human in the exhibition. His are almost tender portraits of ordinary folk doing ordinary stuff in an ordinary farming community in Siaton town, but he manages to capture their moments without the slightest hint of an intrusion, and somehow with a touch of wonder. In “Tanum,” an old man is crouching to plant rice in the paddies, and is bathed in blue and green hues. In “Taligsik,” a child rides a

carabao in the soft rain. In “Rayos,” a girl rides a plow, her red shirt a sharp contrast to the green vastness of surrounding fields. In “Sahid,” a dramatic picture in black and white, fisher folk mend nets, but our eyes center on a middle-aged woman in the center, her face almost passive or sad. That he also surrounds them in arresting color (or perfectly toned black and white) gives his photographs a dimension that brings his stark photojournalism to the level of art.

In

Greg Morales’s photos, the softly poetic comes out of such subtle imageries, so subtle that one is often tempted to see only the ordinary and take them as just that. But take a long look again—those two specks of green in “Islands,” that basket of orange fish in “Lab-as,” that girl in costume in “Negros Beauty”—and what you get is actually a remarkable photographic wit,

a la Manuel Arguilla, that actually subverts the subjects.

Then there is

Robert Tan and his generic shots of Silliman Beach in the sunset—dramatic and beautifully rendered in bombastic saturation and contrast, but alas also perfectly dull in all its ordinariness. Because how many photographs of generic beautiful sunsets are there in the world?

Millions. It doesn’t help that his titles contribute to that blah effect—“Serenity,” “Endless Horizons,” “Golden Opportunity.” All sweet titles signifying nothing. (Let me note, however, that these are the type of pictures that actually sell quite well.) But what we need in a world drowning in pictures is good provocation, a trigger for thought. Or at least a certain newness that separates the amateur trigger-happy shutterbug from the artist.

Good thing, however, that he has saving grace in “Child’s Play,” an eloquent shot of almost unassuming poetry that plays on color tone and shadows. Here, two children only seen in silhouette rush into the sea, while the sea itself rushes in opposite direction, to the shores, its energy seen as the surf that twinkles in the fading light in steel blue.

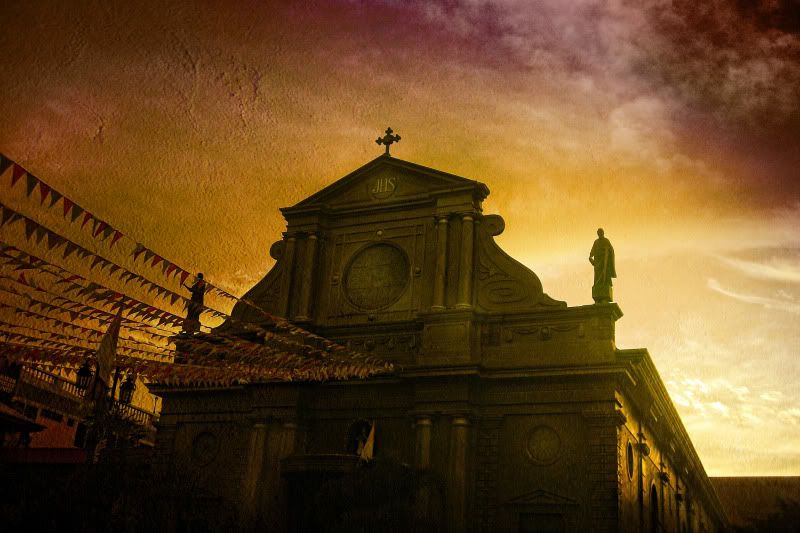

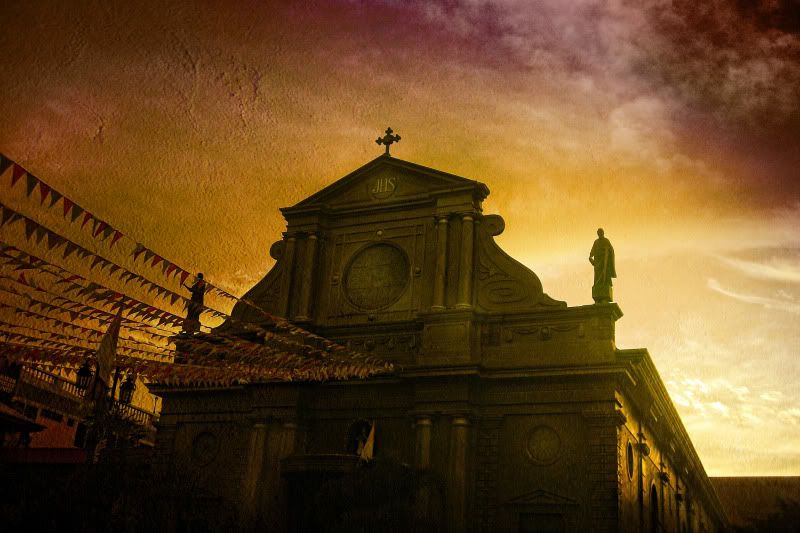

Rilt Dorado

Rilt Dorado has a fascination for the dangerous in the middle of the ordinary or the mundane. His “Dauin Church” merely shows the façade of the said limestone church—but the structure is rendered in menace by the show of dark clouds in the distance. The smiling girl in “The Secrets of Negros Oriental Are Best Seen Through the Eyes of Its People” glows in yellow dress and a yellower aura—but her brightening eyes, they show something almost cat-like. In “Capitol,” the provincial seat of government is seen in a long distance take that follows the long promenade slicing through Freedom Park. It is readily an ordinary night scene—but look at those balls of fluorescent lamps lining the path, especially the one on the left that seems suddenly spectral. In “Thunderstorms in Apo Island,” the picture is a literal demonstration of the title—and we behold the velvet darkness of sea and sky as streaks of sudden light crashes through that dark color. In “Land of Milk(fish) and Honey (Sugar Cane),” an encroaching fog coming straight from the gradient blue of distant mountains approaches a nipa hut built on stilts, as if ready to topple it into the fish pond in the foreground.

John Stevenson, the only American in the lot, has always exhibited a hint of ironic detachment in his previous exhibits around town. He is one who is always ready to see Dumaguete through eyes we are not familiar (or comfortable) with. Which is good of him. He often renders his subjects in strange angles and patched-on stories that underline the obvious and the caricaturish of our Negrense lives, lives that most of us don’t easily recognize (or choose to).

Or perhaps it is just his comic perspective that gives us something new to think about over old things. In “02” for example, Mr. Stevenson takes apart the infamously hideous cement statues of the Paulinian nuns gracing the Rizal Boulevard—by composing a story that has a trio of nuns, their faces hidden by their habits, crack apart into isolation, a lamppost in the middle separating them. Is it a metaphor of something? Knowing Mr. Stevenson, you bet it is.

But his pictures may also be about concealment. In “05,” Mr. Stevenson snaps a photo of a man sleeping on a reclining monobloc chair, his head cropped away by bushes in the foreground. In “04,” a Jollibee billboard—perched on the roof a downtown building—shows the actor Aga Muhlach about to bite into a burger. But it becomes more dramatic when his eyes are cropped away by the roof of the nearby department store, leaving only his gaping, oddly threatening, mouth.

The pictures of

Luigi Anton Borromeo cannot be taken separate from each other. If we do, there is nothing much to get. But as a photo-essay, the set becomes brilliant as a piece of photojournalism, rendered more dramatic by the intricate manipulation of contrast and hues. What we have is a collection called

Cerámica, essentially a depiction of Daro people in the very process of making earthenware. He documents that process with an eye for detail, and from “Moldedo” to “Viruta” to “Lena” to “Potes,” we get a procedural story that becomes more involving because they are also portraits of common clay folk as they go about their ordinary tasks making a living. Who documents these things anymore? Most of us are all too ready to settle with generic beautiful sunsets.

In a sense, the exhibit also becomes a showcase of personal philosophy with regards photography in the Age of Photoshop. Some, like the names above, are relentless in their fidelity to the “real.” What is captured by the camera, unenhanced by any process, becomes sacred testament. Other photographers, however, are not documentarians, but painters, using pixels as their paintbrushes. This is what you see in the photographs of

Charlie Arbolado Sindiong, Phil Calumpang, and

Clee Andro Villasor.

In Mr. Sindiong’s photographs, the personal comes in the form of unexpected angles—composition choices that somehow lend his subject an almost surreal quality that haunts. The protruding limb of a driftwood in “Lumot” is haunting, and becomes more so because of the emphasis given by the saturated clumps of violets and like colors. The same template occurs in his other pieces. There is the dancing girl flanked in yellow in “Sinulog de Jimalalud.” There is the street watcher in the middle of a rainbow of motorcycle hoods in “City Bikes.” But the one that strikes the viewer the most, simply because it has a colorful tenseness that amounts to drama, is his “Baulan Festival.” Here, street dancers seen in full body profile and dressed in the traditional festival garb, are poised in a crouching position, ready for their presentation—something in their stance suggests potential energy about to burst into kinetic.

In Mr. Calumpang’s photos, the danger may be in the overuse of high dynamic range imaging which, in lesser hands, can be the equivalent of an unwanted sugar rush. This is seen in “Dumaguete Circa 2009,” and terribly so in “Migraine Boy.” This is not to say his pictures are bad. They are quite good, but they have been processed to shattering pieces that somehow the poetry becomes throttled before it even has a chance to come out. And yet, oddly enough, the same technique also works very well in “Acacia,” where the titular tree gracing the haunted stretch of San Jose’s Lala-an seems to stand in testament to decay and beauty. In “Dreams of Gold,” a generic mother and child story becomes more dramatic because of a clever use of silhouette and a generous swab of gold that becomes the sky. This is HDR in its best use—highlighting only the necessary to render the best details.

In Mr. Villasor’s images, the hypersharpening of images works because there is no pretense at the documentary. This is photography aspiring towards painting. When it works, it is great. When it doesn't, it becomes pretentious. But the results in this particular exhibit are brilliant, which happens when the elements in the composition—the painstaking layers of images, the relentless adjustments of hue, contrast, burn, and blend—comes together into a haunting, colorful, and arresting finish. You do not see everyday landscape done this way all of the time. What is that texture in the sky that crowns the Cathedral of St. Alexandria in “Escape From Sepia”? What is that fire in the clouds—or is it the cosmos in a war of red—over old Silliman Hall in “Centennial Hall”? And yet we also see that HDR does not necessarily always provide similar drama. In the un-Photoshopped “Persistence of Light,” a driftwood becomes a thing of danger and beauty, and in “Wind-swept Mohon Church,” the said building becomes the steady focus in the staggering dance of the landscape around it.

But it all comes down, eventually, to the possession of the “eye.”

And

Hersley-Ven Casero has it in spades. His pictures are all about the finest textures amidst an overwhelming hue that nevertheless does not overpower. And then he adds one more detail to that pictures by inserting something ... odd. In “Meadow of Blue,” for example, his portrait of Escaño Beach in the early morning, he has a fish grabber working the shallows, dwarfed by the faraway event of an orange sunset, which is in turn dwarfed by the soft blue of rainy clouds that are also reflected on the waters. And then here and there, two alien orbs—actually buoys at rest—seem to shine out an eerie welcome.

But the photograph that strikes me the most is his “Road to Boulevard,” a brilliant study of a street landscape that uses shadows in a dramatic manner. In the light, we see the Boulevards’ faux-antique lamps in the distance, and also a glimpse of Tañon Strait, and in the middle of it all, we see some people walking and some tricycles plying the early morning street. And then all of these are framed elegantly in sepia-like shadows, like a film iris. The result is a haunted romaticism that captures Dumaguete in all its terrible, romantic beauty.

My

My Negros, indeed. What is a good picture of home except a vision of how our hearts see it. To see this exhibit is to behold the hearts of our local photographers—and for the most part, it is an interesting look into how we live.

Labels: art and culture, dumaguete writers workshop, exhibits, negros, photography

[0] This is Where You Bite the Sandwich

GO TO OLDER POSTS

GO TO NEWER POSTS

7:37 PM |

Negros Through the Personal

7:37 PM |

Negros Through the Personal