Sunday, February 28, 2010

2:01 AM |

Taking on Godard

2:01 AM |

Taking on Godard

[edited with new material]

“The way to criticize a movie is to make another movie.”

—Jean-Luc GodardTo make a film is the province of mad people. And the director in the midst of it all—the circus ringmaster, if you will—is the king of mad men. You will have to be when you consider an art form that demands a magician’s patience for dealing with the intricate battles of a collaborative project and the careful attention to billions of details—

What motivation must an actor take for a scene to work? Is that actor even cast right? Is this piece of prop provided by the production designer true to the milieu demanded by the story? What angle or what lens or what lighting design should the cameraman settle for to distill the emotion of a particular set-up? Does the scriptwriter need to change this line? Should the editor take the dailies now and begin cutting? What kind of musical theme is appropriate for the entire picture? Where’s craft for the crew’s food? Where is the producer with the promise of new investment?Real filmmaking is not glamorous. We only think that it is, given the attention we give to it in blogs and TV shows and newspaper lifestyle column inches. Most of us don’t know this—and that is the eternal appeal of moviemaking: the illusion of glamour in front and behind the camera. But when you are bitten by the moviemaking bug, you stay bitten and obsessed by it all. It is like a drug. In the 1973 film Day for Night by François Truffaut, we are introduced to a film crew in their daily struggles to put to celluloid a film called “Meet Pamela,” and in the process we get a glimpse of the drama of filmmaking—the temperamental actors and their eccentricities as well as the rest of the crew. Slowly, we begin to see that for most of them, the final product—the finished film itself—is often the concern they are least invested in. They’re there on the set not for the sake of the film but for the sake of being in the set. They love the temporary bubble of camaraderie that a collaborative project like this brings.

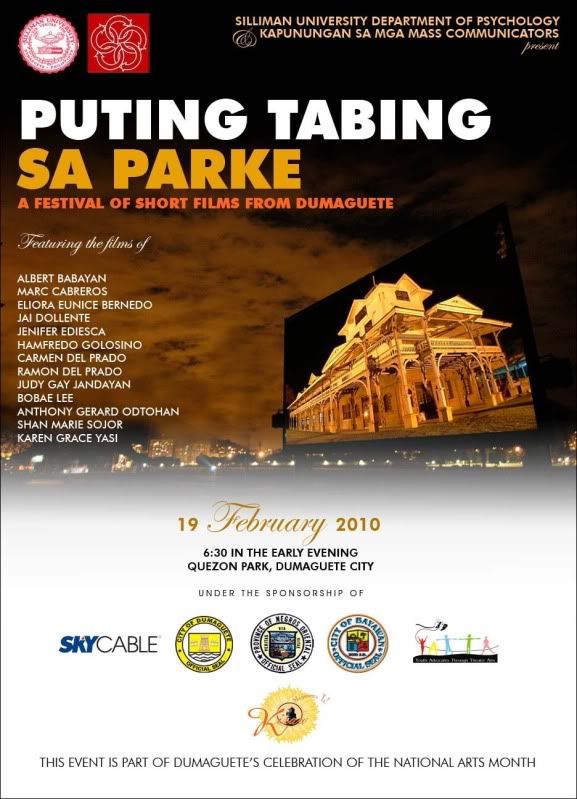

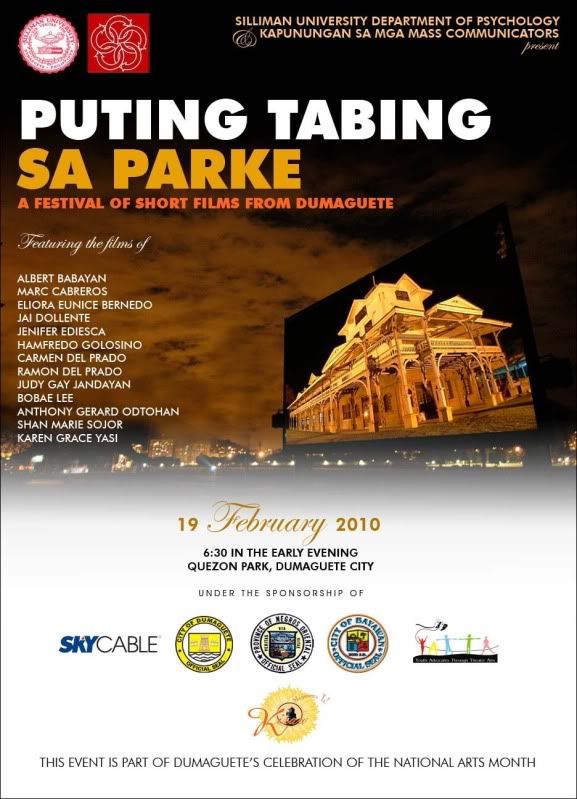

I was reminded of that when I watched my Film Appreciation class in Silliman University—composed of Mass Communication majors Anthony Gerard Odtohan, Eliora Eunice Bernedo, Albert Babaylan, Shan Marie Sojor, Karen Grace Yasi, Marc Cabreros, Hamfredo Golosino, Judy Gay Jandayan, Jenifer Ediesca, and Bobae Lee—struggle with the challenge I gave them last semester. We were learning all throughout the semester the basics of film aesthetics, which included a passing mastery of acting, directing, screenwriting, editing, cinematography, production design, sound, and music. They knew the film elements, but I reminded them quickly that all these would be just stock knowledge they would soon easily forget—unless they put it to use by making films themselves. The great French director Jean-Luc Godard, who gave us such classics as Breathless, once famously said that the best critical take on the movies should not rest merely on the pages of magazines or newspapers filled with movie reviews—it was the very act of filmmaking itself.

And so I told them to make their own short films.

It was the first time for all of them. And the odds were even more challenging beyond their amateur status as filmmakers. With barely any working budget, how do they cram pre-production, production, and post-production in the span of three weeks, before they are supposed to show their finished products on a date I set for them for a mini-film festival of sorts? I had already recruited a motley crew of judges—people from the community who had working knowledge on various aspects of film production—who would render their take on their efforts for that final screening.

And yet—busy and frazzled they might have been in the process—I think they all came out of that experiment richer for the experience. I asked them a series of questions…

What was the experience of filmmaking like? Did you learn anything new about cinema from the experience? Eliora Eunice Bernedo

Eliora Eunice Bernedo (who made the polished

The Birds, the Bees, and All the In-Betweens, a comic look at four teenagers who confront their own brush with sexuality as they munch popcorn and drink soda to an afternoon viewing of

Sin City)

: Filmmaking was like war—probably because I was treading on virgin territory. I somehow had to bleed my mind out just to finish what I started, and couldn’t possibly foresee all of the things that could go wrong.

Albert Babaylan

Albert Babaylan (who made

Coffee, an existential story about a guitarist bored with his day, and the surprise can bring for somebody trapped with writer's block)

: Making the short film opened my mind to certain things I pre-conceived about filmmaking. I learned that film isn’t just about putting things in front of a camera, but that it’s a medium for hard storytelling. It was hard for me, personally, because I had very little help from anyone. All I had was my camera, my other actor, and my girlfriend during the shooting. And it was just me and a friend who recorded the musical score.

Hamfredo Golosino

Hamfredo Golosino (who made the surprisingly effective

Kugi, the story of a hardworking student assistant)

: When I was young, I wanted to make my own movie without thinking of the things to consider in their making. But now, here it was: I was making my own film with much effort.

Shan Marie Sojor

Shan Marie Sojor (who made the artsy story of love lost and love found in

The Gallery)

: Filmmaking was a very good experience for me—the bonds of friendship we made, the fun, everything. I was even interested in making another film. Yes, I learned that cinema is not just filming someone act. It is more that that.

Judy Gay Jandayan

Judy Gay Jandayan (who made a romantic story out of a computer gamer and his long-suffering girlfriend in

DOTA)

: Filmmaking is really exhausting. And it is even more exhausting if you’re the writer, director, producer and cameraman all rolled into one. Watching the movie is very different from actually making it.

Hamfredo: I realized that making film isn’t that easy. It needs ample time to produce. I did not have enough funds as well, considering that I was just a self-supporting student. I had questions, too: What kind of movie should I produce? Who would be my actors? Where I should take my film? Where could I look for the equipment? Do I have enough money? For a first-timer like me, those queries were inescapable. But during the taping, we all had this adrenaline rush to shoot because my actors also had other priorities, and I couldn’t compel them to stay longer. And balancing work and study was not a simple thing to do for me. I felt like being chased by a train wanting to bump me. So I needed to run as fast as I could. But I’m simply a human being and not a machine.

Bobae Lee:

Bobae Lee: Making a film is like ruling a kingdom. You can do whatever you want, but you also have all the responsibilities of doing so. Especially, in our case we are both the director and scriptwriter. Every single decision I make has a huge impact on the result of the movie. I learned how to use the shots that I learned in class and saw in movies to deliver to the audience what I had in mind in certain scenes. I also learned the importance of weather, light, time, and PR in filmmaking.

Jenifer Ediesca

Jenifer Ediesca (who made the ghostly love story

7 Days about a couple and the poetry that binds them)

: Such opportunity doesn’t always happen. I didn’t have enough sleep in the two weeks I made the film. Even in my sleep, I was haunted by the film, but the bright side was taking the challenge, and doing my best—and getting the self-fulfillment that followed after.

Eliora: I can say for sure that filmmaking, especially no budget filmmaking, is riddled with obstacles. Also, the need to sleep is only one of many.

Marc Cabreros

Marc Cabreros (who made the bright, episodic, and comic

The Web Cam, a take on four college students and what they do online)

: I was always behind the camera in most of my film projects, but this was the first time I was REQUIRED to make an actual film. I learned that I was hard in making things right, and making five or more people fit into a small screen. That was hard!

Karen Grace Yasi

Karen Grace Yasi (who made the quirky

The Anniversary, a tale about a guy who encounters all sorts of problem while he goes about his day trying to make a perfect anniversary date for his girlfriend)

: “Great” would be an understatement for the experience. It was my first time to ever make a film, and everything was just so new to me. I’ve always been a laid-back, procrastinating kind of person and this filmmaking experience totally changed my routine. I’ve learned that filmmaking is definitely not as easy as I first thought it would be. It took a great amount of talent to come up with something—a story that could captivate an audience. And even more so: talent to bring this story to life.

Anthony Gerard Odtohan

Anthony Gerard Odtohan (who made a very good documentary about an American running a local orphanage in

Papa Mike and the Rainbow Village)

: It was a challenging project in all areas, especially considering that I opted to go for a documentary. Technically, I’m a rookie although I’ve had minimal experience using video editing software. Psychologically, I was overwhelmed with the whole idea of going on a solo project for a 15-20 minute film. Emotionally, I would picture out scenes and scenarios in my head for multiple times during the day. I guess I was being so hard on myself and taking things so seriously. Physically, I had to log in close to 50 hours (or even more) for the production since I was practically grasping in the dark for creativity as well as sleeping awfully late. Spiritually, I was in constant prayer and even felt moments of despair for my inability. Overall, I realized that documentary filmmakers have no control over what happens on film. You simple have to be there and make sure that the camera is rolling, otherwise you will lose a picture-perfect moment. Also, you have to go through literally hours of footage to pick out what best aids the narrative. When editing, it’s utterly important to remain focused on the centrality of the dramatic structure so that you won’t get lost in the middle of all the clutter (I used Syd Field’s three-act structure as a skeleton). Of course, I am by no means an expert now though I gained a deeper appreciation for the immense difficulty of coming up with a documentary.

Albert: But making the film was fun in the overall. I would never consider what I did as “work.” It was art, and I was like an artist shaping an image into my captured shots.

Judy Gay: If you are part of the audience, you can just critique the film all you want but when you’re the one doing it, you can only hope, pray, and try so hard just so you can come up with at least a viewable and decent output.

What did you learn about yourself from the entire endeavor?Judy Gay: I learned that you cannot be a filmmaker in just one day or in just a blink of an eye...

Jenifer: I won’t choose to be a director!

Judy Gay: ... You really need to have the proper education, the passion, and the utmost patience to produce a movie of your own.

Marc: I was actually patient... and nice.

Jenifer:I learned patience. Nothing happens over time. And this is the time where you have to have a lot of charisma, and tough guts, especially if you’re in the grips of desperation.

Albert: I learned that I love the art of filmmaking, and I look forward to learning more of the craft. It’s a very rewarding art, I’ve always been a fan of anything with a good story—may it be literature, films, music… but it’s a very different thing when you yourself are at the helm of the story.

Hamfredo: I learned that attitude is very important for someone who leads the production. This means patience—towards my actors’ attitude, and most of all, towards myself as director. I also learned to be organized and systematic.

Bobae: I knew that I love music but I also learned I’m very sensitive when it comes to sound. Ever since we were entitled to make our own film, every time I listen to a song I thought: Can I use this song in my movie? If I can, which part and with what kind of shot shall I use? Every time I watch a movie, my antenna for sound effects goes through the roof. Also, I learned that life is a movie without a script. Instead of a script, we all have our special scriptwriter, which is called choice.

Marc: I never thought I could be so polite in times of pressure! I mean, I have always been sarcastic and arrogant to my friends, but this made me so unreasonably calm. I guess I’m a good person after all!

Eliora: I learned that it is good to be wrong every once in awhile and not be afraid to admit it. I couldn’t just lie to myself. Also, more importantly, if I learned that if didn't surround myself with the proper support system (crew) the obstacles could go from challenging to a living hell very quickly. By that I mean – delegation is key. I had to surround myself with eager, imaginative, supportive people that I could depend on so obstacles would seem more like something we could handle together and less like the reason of secretly fantasizing about hitching a ride to space with the hope that my film would never find me.

Anthony: I never realized that I could come up with a documentary on my own as well as being able to edit the film by myself. The project pushed the limits of my creative threshold.

Karen: I have learned—and I will keep this lesson for as long as I live—that the amount of pressure, anxiety, and paranoia one feels when she is in the process of filmmaking is directly proportional to the amount of relief and satisfaction she feels when the movie is shown. A very important lesson on delayed gratification.

Albert: When you are the one telling the story, and having someone grasp at least a bit of what you put out, is an amazing feeling. In my film, the goal was to leave people confused and freaked out a bit, and I remember a few people asking me about my film and telling me they were confused. The feeling of actually getting through your desired effect was great.

Shan: I learned that I can do films, and that I can do more beyond painting. Filmmaking is another form of art that I’m beginning to love.

Anthony:I realized too that prayer and faith in God is crucial in holding me together throughout the entire process.

Do you think that what Jean-Luc Godard said about filmmaking is true? Why?Albert: Godard is indeed right. To fully understand the complex processes involved in making a 1-minute shot of a film is the only way you can fully and credibly criticize that 1-minute shot. One must understand how filmmaking works and how a film is made before he can criticize any film. This is because filmmaking is an art form that involves so many different techniques, perspectives, processes, etc.

Judy Gay: Godard is right in some ways, but in some manner overly ambitious and challenging. You cannot just make the film you really want if you lack the materials needed to produce such a film. You also have to consider the money you will invest and the actors you will cast.

Marc: It’s hard to make films, most especially if you don’t pay your crew or cast. I feel like I do not have the right to tell them what to do. I also had to make the script and direct the whole thing. It’s also hard to make it all come together, for what I wrote and what I imagined came out differently in filming! I had to learn that the hard way, with time pressure, busy schedule, and all the peer pressure! Sheesh! Next time I make a movie, I will make sure I won’t do it alone!

Hamfred: He is absolutely wrong! Can’t we criticize a film without making one? Doesn’t he know that learning can’t only be acquired through experience, but also through observation?

Bobae: Well, for me, I think what he said is true. First, you cannot imagine enough how hard it is to make a film. When I heard I needed to make a film at the end of the semester, I was so shocked, astonished, surprised, as was everybody in my class. But it was one of the great challenges in my life. Second, you get to know deeper about the filmmaking process.

Shan: Experience is the best teacher. We can’t criticize something if we don’t know the whole process.

Bobae: Yeah, to criticize something, you need to know why it had to be criticized. For example, you may not like particular shots of a movie. But it doesn’t mean you can just criticize it because you didn’t like it. Maybe the director used that shot to emphasize the situation, or to get certain reactions from the audience. Now, I cannot really criticize easily, like before. I didn’t know this much about film.

Karen: I believe that the beauty of a film is not only seen when we watch it, but when we realize how the people behind the film were able to gather all creativity and come up with something worth watching. It’s really easy to criticize a film when you just look at it in the audience’s perspective, but when you’re exposed to all the challenges the process of filmmaking comes with, you’ll eventually learn to appreciate a good movie when you see one.

Jenifer: Me, I vow to never ever again criticize a movie, no matter how

banga it is. It is an all-out effort for all concerned. If one fails, the movie fails as well.

Eliora: I would critique films before without even thinking. I’d fail to see the whole experience (from its technicalities, good acting, etc). I can certainly say now that ignorance is not bliss—it’s a waste. Because doing almost everything caused me to see things in a clearer and different light. When my turn came, the criticism was like an avalanche, each of my amateurish mistakes rolling off my friends’ tongues was clobbering me at the back of the head. I was blown wide open. It was hard to be able to separate myself from the work and it hurt. But it felt so satisfying as well when it was praised.

Anthony: Still, I don’t think it’s necessarily true that you have to make your own film as the only license to be a good critic. I’m sure that there are some critics out there who have that gift. However, I’m not one of them. I think that if one involves himself in the actual process of filmmaking, from start to finish, there will be deeper insights gained. There will be a sharpening of the critical eye to see the intentionality of the director and the cinematic methods used (type of shots, lights, sound, etc) which overall can affect the value (or non-value) of a film.

Labels: art and culture, dumaguete, film, school, silliman

[0] This is Where You Bite the Sandwich

GO TO OLDER POSTS

GO TO NEWER POSTS

2:01 AM |

Taking on Godard

2:01 AM |

Taking on Godard