Monday, October 13, 2014

4:46 AM |

Oscar and the Asian Film

4:46 AM |

Oscar and the Asian Film

Part 1 of a Series

In all my years of watching the Oscars and following the race among the contenders that precede each annual telecast of Hollywood's glamourised pat-on-the-back, I have been drawn to one category more than the usual: the award for Best Foreign Language Film.

When I was a younger cinephile, the award struck me as one that was the very illustration of the "magnanimity" of the Academy, which has chosen to single out a film (out of five nominees) that does not come out of the usual American cinematic machinery, to shine some spotlight on the national cinema of some other country that was not the United States, nor its close cousin the United Kingdom.

It also promised me this possibility: here was an Oscar that can truly be won by a Filipino filmmaker. All we need to do, as the category's rules demand, is to have the country's institutional representative chose a title from among those who have undergone a week's worth of qualifying run, then submit the title to the Academy, and then wait for the Academy's own subcommittee overseeing the category to whittle a long-list of usually 70+ titles, to a short list of nine, out of which the final five are chosen.

The older cinephile in me has since realised that all these is easier said than done. More than politics are involved in the grind towards the selection of the nine.

There is also the relentless campaign to get noticed. How does one film among 70 get noticed? Doing the festival circuit -- Cannes, Berlin, Venice, Toronto, Sundance, New York -- is one answer: the better films get better notices, and hopefully word-of-mouth will carry the title through the looong race. Compiling the better notices from important film critics is another. At year's end, the circles they run in usually produce their top-tens and unveil the winners of their award listings. The more a film gets mentioned, the more you are "in the conversation."

It is a trickier process for a "foreign language film," given the bias towards Hollywood fare in these considerations. The one Filipino film, I think, that came closest to surviving this process was Aureaus Solito's

Ang Pagdadalaga ni Maximo Oliveros, which won the coveted Teddy at the Berlinale and snagged a nomination at the Independent Spirit Awards, while getting generous attention from critics and list-makers. But when the 2006 Oscar's short list was finally revealed, the nominations went to Germany, Denmark, Algeria, Mexico, and Canada: two European countries, one African (a rarity -- but not a rarity for Algeria), one Latin American, and one North American (but a film that does have an Asian theme). In 2007, a film from a most unusual Asian country made the shortlist, but it was Kazakhstan's first attempt to submit a film to the Oscar -- and sometimes being a first-timer helps: at least it brings a heightening of attention by those who are voting. ("The first submission from that country, eh? Let's take a look...")

The Philippines has never won a competitive Oscar for Best Foreign Language Film, even when it has one of the oldest national cinemas in the world, and even when it actually started sending in submissions in 1956, the first year of the category when it went full-merit. (We sent in Lamberto Avellana's

Anak Dalita. Federico Fellini's

La Strada, from Italy, won.)

Before 1956, the Oscars did recognise certain foreign films as having been the best of their respective years -- but it was not a competitive award. In 1953, Manuel Conde's

Genghis Khan -- which had wowed the Venice Film Festival -- was considered for a special citation, but it never got the award. (No foreign film got the award that year.) In those pre-competitive years, only three countries ever merited Oscar distinction:

Italy (

Shoeshine in 1947 and

The Bicycle Thief in 1949),

France (

Monsieur Vincent in 1948,

The Walls of Malapaga in 1950, and

Forbidden Games in 1952), and

Japan (

Rashomon in 1951,

Gate of Hell in 1954, and

Samurai: The Legend of Musashi in 1955). As far as Oscar was concerned, these were the only countries in the world aside from the U.S. and the U.K. that were making films in those years.

But the Philippines has not always sent in submissions. In the 1960s, we only sent twice: in 1961 with Gerardo de León's

The Moises Padilla Story, and in 1967 with Luis Nepomuceno's

Dahil sa Isang Bulaklak. In the 1970s, we only sent once: in 1976, with Eddie Romero's

Ganito Kami Noon, Paano Kayo Ngayon. In the 1980s, we only sent in twice: in 1984 with Marilou Diaz-Abaya's

Karnal, and in 1985 with Lino Brocka's

Bayan Ko: Kapit sa Patalim. Imagine all the other magnificent films in the First and Second Golden Ages of Philippine Cinema that went unsubmitted.

But we have regularly sent in submissions in the 1990s and thereafter, starting in 1995 with Carlos Sigiuon-Reyna's

Inagaw Mo ang Lahat, and followed by Tikoy Aguiluz's

Segurista in 1996, Marilou Diaz-Abaya's

Milagros in 1997 and

Sa Pusod ng Dagat in 1998, Gil Portes's

Saranggola in 1999, Rory Quintos'

Anak in 2000, Gil Portes again with

Gatas... Sa Dibdib ng Kaaway in 2001 and

Mga Munting Tinig in 2002, Chito Roño's

Dekada '70 in 2003, Mark Meily's

Crying Ladies in 2004, none in 2005 (because of the Film Academy of the Philippines' reasoning that the Oscars were not notified of their change in office address -- thus the "non-delivery" of the official invitation to submit), Auraeus Solito's

Ang Pagdadalaga ni Maximo Oliveros in 2006, Adolfo Alix Jr.'s

Donsol in 2007, Dante Nico Garcia's

Ploning in 2008, Soxie Topacio's

Ded na si Lolo in 2009, Dondon Santos's

Noy in 2010, Marlon Rivera's

Ang Babae sa Septic Tank in 2011, Jun Robles Lana's

Bwakaw in 2012, Hannah Espia's

Transit in 2013, and now Lav Diaz's

Norte, Hangganan ng Kasaysayan in 2014. Sometimes, some of the title sent for consideration can be cause for much head-scratching, with

Noy standing out as the worst possible contender. And what gives the popularity of Gil Portes whose cinema is, at best, merely "decently-made"?

Our own politics obscure enough our chances for Oscar gold, so one can only imagine the vagueness that transpires from the bigger politics of the international film world. In the given morass of choices and politicking, I can understand an Academy member, who is tasked to be part of the special committee to sift through the gargantuan number of foreign language film submissions, to decide to fall in with the easier alternative of dealing only with national cinemas of considerable track record, or of considerable "undeniability." By that, we mean the countries of Europe, of course, with token representations of the often-cannot-be-ignored countries from other continents (South Africa and Algeria from Africa, Japan and China from Asia's Far East and Israel from the Middle East, Argentina and Mexico from Latin America, and that's basically it.) The stray entry from the unlikely country not usually within Oscar's radar (Cuba, Vietnam, Nepal, Kazakhstan, Cambodia, Vietnam, Ivory Coast, and Nicaragua) becomes the "surprise" tokenism that assures everyone the world has been gone over with a fine-tooth comb.

But here are some statistics:

Twenty-four (24) European countries have so far merited nominations. Compare

that with only three countries with nominations from Africa. Or only nine countries with nominations from Latin America. (Uruguay's nomination in 1992 was, however, rescinded. And there is the curious case of Puerto Rico, essentially part of the United States, but which garnered a nomination in 1989.) From Asia, there are four countries with nominations from East Asia, two from South Asia, two from Southeast Asia, and four from the Middle East -- 12 in all. Canada as the lone North American country that is not the U.S. has been nominated several times (7 times to be exact).

Almost

all European countries have been nominated --

except for Ireland, Portugal, and Romania for the major ones (quite a surprise), and Luxembourg, Albania, Cyprus, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Turkey, Bulgaria, San Marino, Vatican City, Monaco, Andorra, Armenia, Belarus, Azerbaijan, Liechtenstein, Lithuania, Malta, Moldova, and the Ukraine. And I'm not exactly sure how to consider Croatia, Montenegro, Serbia, and Slovenia, because as constituents parts of the former Yugoslavia, they managed to secure six nominations for that (now-nonexistent) country. The same goes for Slovakia, which, as part of the former Czechoslovakia, also garnered six nominations. Since separating from its sister country, it has not garnered any nominations all its own, but the Czech Republic has three nominations thus far.

From a total of 331 nominations (including the special ones) since 1947, 248 or 75% have gone to European countries. Asia clocks in a very distant second with 45 nominations, or 14%. Latin America follows with 24, or 7%. Africa and North America's Canada, with seven nominations each, contribute 2% respectively.

Of the top five countries with most nominations, France leads with a record 38, and Italy follows with 30. (But both share an award in a 1950 co-production with René Clément's

The Walls of Malapaga.) Spain is third with 20, and then Germany (including nominations for West Germany) with 18. Japan is fifth with most nominations with 15. But Sweden and Russia (including nominations for the Soviet Union) follow very closely with 14 nominations each.

Among the winners, 54 Oscars, or a whooping 81%, have gone to European countries. Only 6 Oscars, or 9%, have gone to Asian countries. Africa, with three wins, constitutes 4%. Argentina's two wins constitute 3% for Latin America. Canada's one win is the remaining 1%.

Taking a look at the European winners, Italy is the over-all champion with 14 wins, followed by France with 12 wins. Russia/Soviet Union and Spain come close with 4 wins each. Sweden, the Czech Republic, Germany, the Netherlands, and Denmark follow with three wins (including two for the Czech Republic, when it was part of Czechoslovakia). Switzerland and Austria have two wins, and there are the singular wins for Hungary and Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Japan, with four wins, has the most Oscars for a non-European country, followed by Argentina with its two wins.

In other words, the Oscars is very much a Europe-centric affair.

As a matter of curiosity, I took note of the years where Europe essentially blocked off the rest of the world with nominations, expecting to find a rarity. To my surprise, there were

12 years (out of 57 since 1956) -- specifically 1958, 1959, 1966, 1968, 1970, 1978, 1979, 1985, 1986, 1987, 1992, and 1996 --

where there were only European nominees. That's a lot of years of being blind from the rest of world cinema.

I want to focus for now on the Asian film, however, and how it has fared exactly with Oscars. When I talk of the Asian film, I consider the term with much respect to geography, and mostly considering the imprecise divide provided by the Urals. Hence, the Asian film does not only include those from East Asia (China, Japan, Taiwan, South Korea, North Korea, Mongolia, Hong Kong, and Macau), or Southeast Asia (the Philippines, Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand, Singapore, Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos, Burma/Myanmar, Brunei, East Timor, and Papua New Guinea), or South Asia (India, Sri Lanka, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Nepal, and Bhutan) -- but also, in my estimation, and perhaps problematically so, the films from the Middle East (which includes Israel, Palestine, Iran, Iraq, Saudi Arabia, Yemen, Oman, United Arab Emirates, Qatar, Kuwait, Afghanistan, Tajikistan, Kyrgystan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, Syria, Lebanon, and Jordan). Turkey, for all its wishes to be considered part of Europe, has not been included.

I have attempted to consider the Asian Oscar in terms of the chronological in nominations. The countries below are listed according to the first time they were ever nominated for a Best Foreign Language Film Oscar. I have endeavored to specify the number of wins and nominations, taking note of the films nominated for each particular year. Asterisks (*) denote winning films.

JAPAN

Wins:

JAPAN

Wins: 4 (including 3 pre-competitive special citations)

Nominations: 15

1951

Rashomon*

1954

Gate of Hell*

1955

Samurai, The Legend of Musashi*

1956

Harp of Burma

1961

Immortal Love

1963

Twin Sisters of Kyoto

1964

Woman in the Dunes

1965

Kwaidan

1967

Portrait of Chieko

1971

Dodeska-den

1975

Sandakan No. 8

1980

Kagemusha

1981

Muddy River

2003

The Twilight Samurai

2008

Departures*

INDIA

Wins:

INDIA

Wins: 0

Nominations: 3

1957

Mother India

1988

Salaam Bombay!

2001

Lagaan

ISRAEL

Wins:

ISRAEL

Wins: 0

Nominations: 10

1964

Sallah

1971

The Policeman

1972

I Love You Rosa

1973

The House on Chelouche Street

1977

Operation Thunderbolt

1984

Camila

2007

Beaufort

2008

Waltz With Bashir

2009

Ajami

2011

Footnote

CHINA

Wins:

CHINA

Wins: 0

Nominations: 2

1990

Ju Dou

2002

Hero

HONG KONG

Wins:

HONG KONG

Wins: 0

Nominations: 2

1991

Raise the Red Lantern

1993

Farewell My Concubine

VIETNAM

Wins:

VIETNAM

Wins: 0

Nominations: 1

1993

The Scent of Green Papaya

TAIWAN

Wins:

TAIWAN

Wins: 1

Nominations: 3

1993

The Wedding Banquet

1994

Eat Drink Man Woman

2000

Crouching Tiger Hidden Dragon*

IRAN

Wins:

IRAN

Wins: 1

Nominations: 2

1998

Children of Heaven

2011

A Separation

NEPAL

Wins:

NEPAL

Wins: 0

Nominations: 1

1999

Caravan/Himalaya

PALESTINE

Wins:

PALESTINE

Wins: 0

Nominations: 2

2005

Paradise Now

2013

Omar

KAZAKHSTAN

Wins:

KAZAKHSTAN

Wins: 0

Nominations: 1

2007

Mongol

CAMBODIA

Wins:

CAMBODIA

Wins: 0

Nominations: 1

2013

The Missing Picture

(There is the special case of the Soviet Union in 1975 when it won for

Dezu Uzala, which was a Japanese co-production directed by the great Akira Kurosawa. It is a very much an Asian film, but for the sake of clean statistics, I am not considering it.)

But what can we learn from the nominations above?

First, it's good to be Japan. But Japan was the first Asian country to really make the rounds of the international festival circuit, and the films of Akira Kurosawa (and later on, Yasujiro Ozu) essentially opened the eyes of the world to the possibilities of Japanese cinema. It has earned the right of "first consideration," so to speak. Any Japanese film, by virtue of that long tradition of recognised excellence, will always be something for Oscar to take a look at. Any year is theirs to lose in terms of being nominated, the same privilege accorded to Italy and France.

Second, it's good to be the new kid on the block. Vietnam, Nepal, and Kazakhstan were curious first timers when they got their first nominations. They have not been nominated since their years.

Third, it pays to be quirky, especially if quirky has something to do with some dark historical material. Cambodia has submitted twice before it hit pay dirt: in 1994 with

Rice People, and then in 2012 with

Lost Loves, both with no nominations. But 2013's

The Missing Picture was quirky: it was a documentary of Pol Pot's purge of the country, but done in claymation. It borrowed from Israel's technique of 2007:

Waltz With Bashir was an animated documentary about Israeli soldiers fighting a godless war in Lebanon. Those things get noticed.

Fourth, it's good to be a country that is always headline news. For better or for worse, Palestine has instant name recall. It is always newsworthy. I wish the Philippines submitted something in 1986, when its People Power revolution made the country a household name all over the world. That could have translated to a nomination. We didn't send anything. But then again, nor did we produce anything of considerable excellence.

Lumuhod Ka Sa Lupa! and

Donggalo Massacre, anyone?

Fifth, having one of the oldest national cinemas in the world does not mean anything. Take a look at India's meagre three nominations, and not one film by Satyajit Ray among them, although one of his film (

The Chess Players) did get submitted, but did not garner a nomination, in 1978.

Sixth, it pays to be a juggernaut in the American domestic box office. Ang Lee's

Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon -- Taiwan's submission in 2000 -- could not be denied its win. It was already angling for a much bigger prize -- the Best Picture Oscar itself -- but I guess Academy voters thought it safe, and more American, to give Lee's film the lesser statuette.

Gladiator won instead.

Seventh, it pays to be Ang Lee. It has submitted a total of 40 times, but Taiwan only gets nominations every time it submits a film directed by Ang Lee.

And so, it is mostly a hit-and-run affair with Oscars and the Asian film.

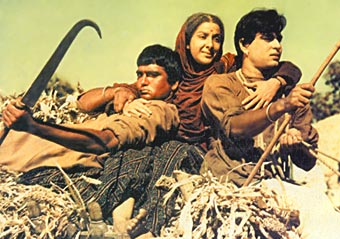

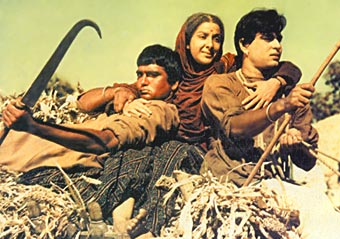

In 1993, however, a miracle happened. In a year that was kind to Asian film, three were nominated for the Oscars: Chen Kaige's

Farewell My Concubine from Hong Kong, Trần Anh Hùng's

The Scent of Green Papaya from Vietnam, and Ang Lee's

The Wedding Banquet from Taiwan. They competed for the Oscar statuette along with Fernando Trueba's

Belle Époque from Spain and Paul Turner's

Hedd Wyn from United Kingdom. The Asian films dominated the conversation that year, but guess which won...

I'm going to see all five 1993 nominees again, and see how each measure up today. Did the right film win?

To be continued...Labels: film, oscar

[0] This is Where You Bite the Sandwich

GO TO OLDER POSTS

GO TO NEWER POSTS

4:46 AM |

Oscar and the Asian Film

4:46 AM |

Oscar and the Asian Film