Monday, April 04, 2011

1:19 AM |

We All Complete

1:19 AM |

We All Complete

Perhaps it was not such a good idea to jump right into Mark Romanek's adaptation of

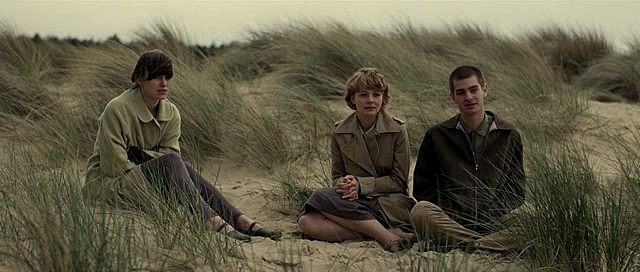

Never Let Me Go [2010], so soon after finishing the novel by Kazuo Ishiguro. Reading a book allows us complete freedom in the construction of the imagined world presented to us on the page -- and the minute details of Hailsham, the Cottages, Norfolk, and then the anonymous Recovery Centers that dot the landscape of the novel are still fresh in the hold of my imagination.

The exactitude of a cinematic adaptation is often a disappointment, and the things that are excised from the literature to fit the constraints of a feature film's running time is often too glaring. And we always come way saying, "The book is better than the film." But sometimes, some films get a good balance of things, such as Steve Kloves' efforts in J.K. Rowling's

Harry Potter film series. Screenwriter Christopher Hampton and director Joe Wright, in adapting the Ian McEwan novel

Atonement [2007], also get it right: they are able to stage in the regular run of the film all the emotional inflections of the characters, all the right moments of drama and revelation, and all the set pieces [the Tallis mansion, the war-ravaged Dunkirk...] which are sumptuously recreated from the novel; there's faithfulness to the book,

but also a vibrant originality all its own that keeps it from being a dry exercise in adaptation.

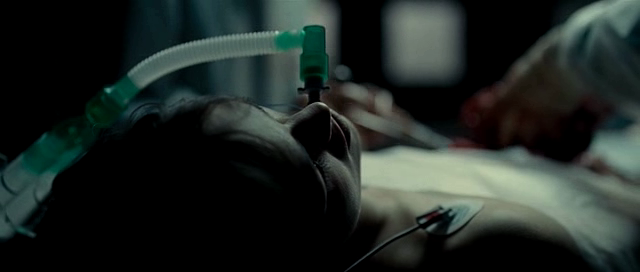

Alex Garland, also an acclaimed novelist, stays true to the chronology of the Ishiguro story, but must have been at pains in how to exactly put all of that down on paper and on celluloid, and the strain shows. Kathy H.'s tale -- compelling on the page because of its gripping, if too matter-of-fact, rendering of the various lives and secrets in Hailsham and the Cottages, and her unique way of making a veritable cliffhanger out of every incident she tells -- is perhaps difficult to film, since she does not exactly tell her story in a chronological way. She goes about it in a roundabout manner, always sifting through time and memory, plucking details out of the air of what she remembers, as she tells this "story": three friends -- Kathy, Ruth, and Tommy -- share a close-knit childhood in a special private school, where they are sheltered from the realities of the outside world for some reason, where they go through regimented ways and traditions not exactly explained to them, where they are not exactly told about their fates but are conditioned to accept them whatever those fates might turn out to be; and then they "graduate" to the real world in the Cottages where they confront the triangle they form; and then there's the harsher realities of becoming Carers and Donors and the inevitability of Completing and the precarious hope they cultivate for avoiding the fate forced on them...

Garland puts all that in, but does not manage to get us emotionally involved, and maybe that's because he omits what's necessary, and sets to tell the story in a straightforward manner rather than the emotionally informed roller coaster of the book's narrative. Take, for example, the stress on the Art for Madame's Gallery that becomes vital in the last third of the film (and in the book). The foregrounding of the relevance for this plot point is totally absent from the film, which inexplicably rushes through the Hailsham years as if this part of the story is nothing more than an unimportant flashback. What Garland and Romanek do not get is that the very theme of the story is memory. Everything about the Hailsham past and what happens in it informs the actions of the characters, including Ruth's treachery and eventual wish for redemption, and including the importance of the "art" Madame collects for her "Gallery." What foregrounds that in the first third of the film? Just Tommy drawing a misshapen elephant. The film doesn't even explain why it makes Tommy confess to Madame in the end why none of his childhood art ever got chosen for the Gallery.

But I'm quibbling too much. The film has its merits: it is beautiful, the music by Rachel Portman is perfection, and it is well cast. Carey Mulligan as Kathy brings out with such truth the quiet sureness, the knowing fierceness, and the subtle intelligence we glimpsed at from the pages.

In the end [

spoiler alert!], the film quotes partly from the book, and has Kathy muttering this melancholy cry of acceptance at the Norfolk countryside -- that place "where all our lost things can be found" (a point the film never picks up): "I come here and imagine that this is the spot where everything I've lost since my childhood is washed out. I tell myself, if that were true, and I waited long enough then a tiny figure would appear on the horizon across the field and gradually get larger until I'd see it was Tommy. He'd wave. And maybe call. I don't know if the fantasy go beyond that, I can't let it."

The quote from the book stops there, but the film adaptation goes on this way: "I remind myself I was lucky to have had any time with him at all. What I'm not sure about, is if our lives have been so different from the lives of the people we save.

We all complete. Maybe none of us really understand what we've lived through, or feel we've had enough time."

And I found that point devastatingly true, and also ultimately sad.

Labels: books, film, screenplay

[6] This is Where You Bite the Sandwich

GO TO OLDER POSTS

GO TO NEWER POSTS

1:19 AM |

We All Complete

1:19 AM |

We All Complete