Tuesday, May 22, 2012

3:29 AM |

The Three Virtuosos of the Photographic Eye

3:29 AM |

The Three Virtuosos of the Photographic Eye

Part 8 of the Dumaguete Design Upstarts Series

Is there a glut of photographers in Dumaguete? Without batting an eyelash, my answer is yes—and not just in Dumaguete. The delusion of photographic skill is everywhere, and the evidence is flooding the feeds of our Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Tumblr, Flickr… I’ve said it before. The exploding number of shutterbugs is a phenomenon directly proportional to the increasing democracy of digital photography, and it has become a joke in photography circles that these days anyone with an SLR seems to think he can saunter into the world and proclaim himself a “photographer.” That the vast majority do not call themselves thus is an act of mercy by the universe—amateurs thankfully in acknowledgment of their limitations. For a few that do, their sheer number often threatens to overwhelm the integrity (and asking price) of the profession, leaving the serious professionals in ridiculous competition with wannabes who invariably take commissions with a grain of salt, but don’t often deliver. As a result, the price for photographic talent may be bottoming out.

Of late, we get waves upon waves of photographic blahness—ad infinitum and ad nauseum—of leaves and flowers, sunrises and sunsets, women in bikinis, men in briefs. Most of these are slyly tweaked in Photoshop (or, heavens, Instagram) to approximate some glossy finish. Truth to tell, one or two of these pictures are beautiful all right, an accident of timing and angle; but in the context of body of work, the eye—the crucial eye—sans Photoshop is missing. Nothing draws you in beyond the initial “hmmm.” There’s no magic.

In the ocean of photographers in Dumaguete, a few do stand out. There’s Kat Banay and Hersley Ven Casero, whom I have featured in this series separately. In the front ranks, you will find Mikko Lim, DX Lapid, Clee Andro Villasor, Kim Cuevas, David Jules Mamhot, Zon Lee, Alma Zosan Alcoran, Paul Benzi Florendo, Darrell Bryan Rosales, Jerick Hernani, Aris Ramiro, Charlie Sindiong, Jaysie Tayko, Phil Calumpang—and I may be missing others, but this is by no means an exhaustive list.

Yet I keep turning to the works of three young men whose technical proficiency and hard-earned professional integrity seem to coincide with the gift of the elusive eye: the photographs of Luigi Anton Borromeo, Brian Arbas Rimer, and Urich Calumpang seem to me to be the prime examples of budding artistry in overarching mastery of medium. Whether with a regular still camera, a video, or an iPod, these three have exhibited an uncanny understanding of photographic language. They have demonstrated that it is not enough to own the proper expensive gadgets and certainly not enough to know the tweak buttons of post-processing applications. Great photography is the telling of an evocative story—and the best of them, for the lack of a better word, move you. The works of these three have moved countless people—and they know how to tell a story.

For all three, a childhood brush with the camera proved to be the push to a life-long drive to perfectly capture something of life. For Mr. Borromeo specifically, the interest had childhood roots, but it was also a late-blooming love affair. “Film was expensive,” was his explanation. He was already all of 20 years old when he really started taking photography seriously, digital this time. But the fascination had always been there; and the motivation, too. “I’m always motivated to shoot,” he said. “I get that from Ansel Adams who once said, ‘The single most important component of a camera is the twelve inches behind it.’”

Luigi Anton Borromeo

And shoot he does, although the whole seriousness of the craft was something he had to get used to. “Intimidation is my weakness,” Mr. Borromeo said. “I easily get intimidated when I’m in a crowd of photographers who have greater experiences and have better equipment than I do. I own an entry-level digital reflex camera. So the only way I can compensate is to do my best to make a picture seem like it was shot on an expensive camera.” Which is perhaps the perfect retort to anyone who believes gadget trumps over talent. (And there are certainly a lot of them.)

Portrait of Kylie Montebon by Luigi Anton Borromeo

Mr. Borromeo’s forte is environmental portraiture. “I was inspired by Joe McNally,” he said, “especially in how he lights his subjects. He does this in very creative ways. He utilizes ambient and artificial lights very well, making the picture interesting. His technique gives his subject more dynamism and depth, without exactly going overboard.” His portrait of Kylie Montebon is a good example of that influence—lighting and depth and texture and subject’s beauty in a great mix, it cannot help but tell a story. This is not merely a girl posing. This is a girl with a story captured well—a hesitation in full make-up, wary and unfeeling at the same time. That she caresses a tree, its texture barely there, adds to an effect of obliqueness.

Brian Arbas Rimer, on the other hand, seems to have found firm footing in both still photography and video—and his own love affair with capturing image also has its roots in childhood. “My dad used to bring his camera everywhere we went, and we kind of got used to the idea of photographing every detail of our family vacations,” he said. “I got my first film camera when I was 7, and since then, I’ve fallen in love with photography.” He started devouring the pictures of Scott Kelby and the photographs he saw in National Geographic. He started aiming for what he saw in them: “a perfect shot, where one image perfectly captures an entire event.” That calls, of course, for an instinctive feel for the grand moment that is often fleeting, which is something that will inform his future work.

Brian Arbas Rimer

But Mr. Rimer’s real education sprang from encounters with local wedding photographers—Dino Lara, Rock Paper Scissors, Paul Vincent, and Nelwin Uy. “I noticed that they concentrated more on people’s expressions rather than on technicalities,” he said. The technicalities, for him, can often prove to be cumbersome if allowed to overwhelm the shoot. Mr. Rimer prefers instinct above all, especially the instinct to capture emotion in people that, in his own words, “can be universally understood.” “Photography,” he once said, “is the language I use to translate other cultures.”

One sees all these in his collective work that seems to celebrate the candid. “I like to take a step back and let things happen on their own rather than setting up or posing a picture,” he said.

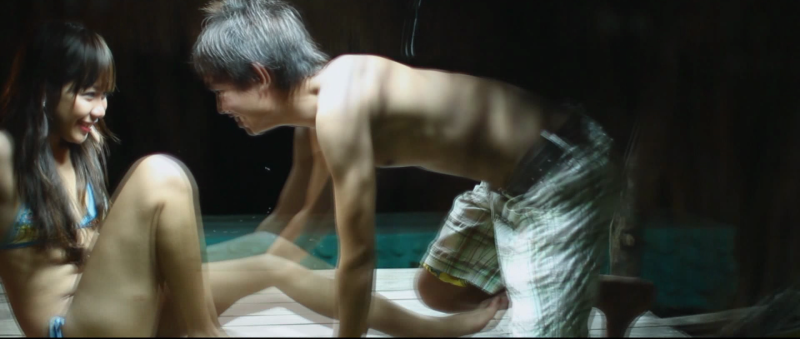

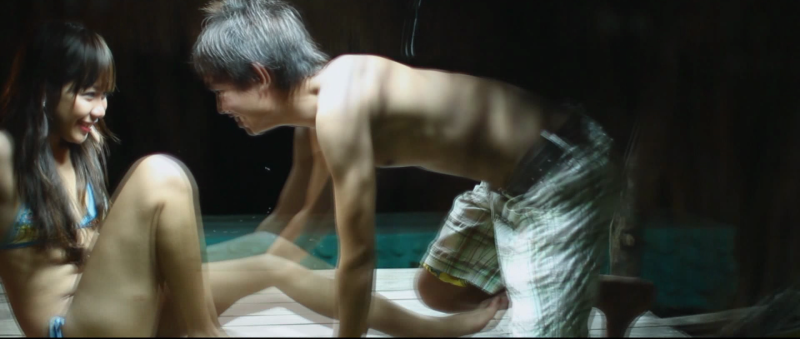

Scene from Amor y Sangre by Luigi Anton Borromeo and Kim Cuevas

With Mr. Cuevas, Mr. Rimer has also done cinematography for some local short films, notably a NORSU-produced film titled Amor y Sangre. There is a sequence in the film—of two lovers being amorous in a beach-side cottage at night—that jumps at me for the inventiveness of its tracking shot which at once relays playfulness and illicitness requisite in the scene. “I started to get interested into cinematography not that long ago since HD movie recording came out,” Mr. Rimer said. “Bringing movement to pictures was something totally new for me, a still photographer. First it started out as something I did for fun, until I began learning more techniques. It soon required new equipment, and once again it became another passion.” Of Mr. Rimer’s forays into film, he cites as influences the documentaries of Jason Magbanua, Threelogy, Mayad Studios, Chase Jarvis, and Vincent Laforet.

For Urich Calumpang, photography began as a holiday gift when he was younger. “I got my first camera from my mom as a Christmas gift,” he said. “It was a Casio point-and-shoot camera, and I started taking pictures of the usual flowers ands sunrises and sunsets. The usual macros. What was just there, I shot. I was 17. I had that camera for around a year, and soon it broke. So I got another camera, which was still a point-and-shoot one, a Kodak. But I wasn’t satisfied with my pictures, and so I worked abroad, in California, for two months, and saved up for a better camera. Which was a Canon 550D, which I use until now.”

Urich Calumpang by Francis Silva

That was when he started shooting for real: people and streets and assorted events. “It was mostly just everything I saw that interested me,” he said. “I’ve learned a lot from the photographs of Ansel Adams. And locally, the works of Hersley-Ven Casero. I soon met the most awesome photographers who mentored me and taught me a lot of things, and helped me. I learned the ethics, I learned how to take solid shots, how to cover events, how to dress appropriately. There’s Greg Morales. He’s like my second dad. And I’m most thankful that we got to know each other.”

For Mr. Calumpang, the process of taking good photographs is just letting the creative juices flow. “I have learned not to suppress it. It’s there, within you. That flows in you,” he said. And so, every single day, he brings with him anything that has a camera—a phone, an iPod, whatever. “Wherever I go, I’m always ready to take pictures of things, everyday things that people often take for granted. Some of the most wonderful photographs I’ve gotten come from the most common things usually taken for granted. But my process is quite simple: I feel it, the potential photograph. When you look at something, and you picture it in your mind…when you are able to think of that something, you can actually take that very picture.”

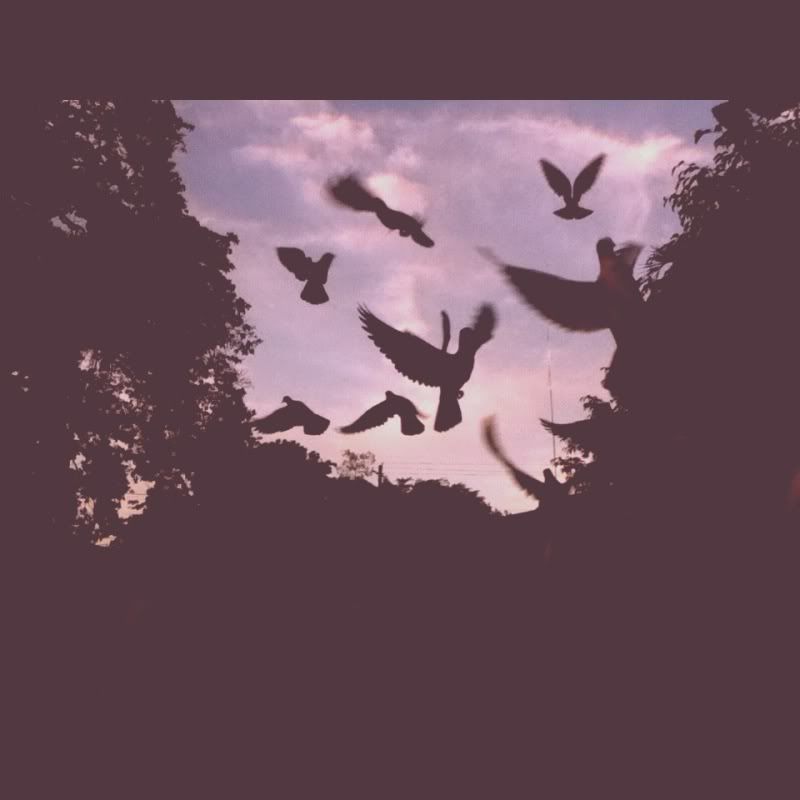

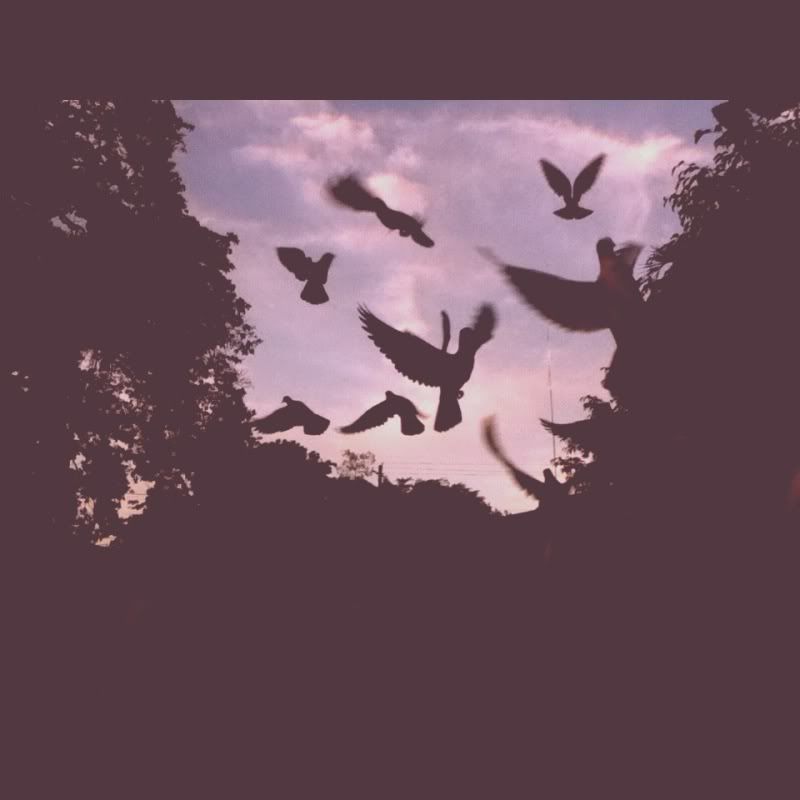

His regular commissioned photos, always without Photoshop, have a sparkling crispness to them that belie an instinctive feel for moment and light and angle. But when he goes for a stylistic bent, he bends color to a 70s Polaroid feel. “These photos give me that nostalgic feeling,” he said, “and a sense of euphoria.” Which may be understandable for somebody who is fond, musically, of standards and the whole Beatles repertoire. “I’ve always wondered what it must have felt like, to live in that age, when my music idols were actually very much a part of the era,” he said. And in wonderment, he tries to recapture an era with photography.

And so we thus know that Mr. Calumpang has his own stylistic quirk, often best captured in his experiments with Instagram, using his iPod.

Pigeons 2, taken with Instagram, by Urich Calumpang

But his fascination for the extraordinary and the symmetrical in the common perhaps defines him best as a photographer—and you see that in his shots of architectural detail, of lines, of geometrical shapes. All these from everyday objects and scenes, of course. This appeals to the obsessive compulsive in him. “I love symmetry. I love it because it has balance, it creates a sense of completeness, which best describes my personality as an O.C. guy. I put more emphasis on balance, and seeing things that are in place makes me at ease,” he said.

A sense of balance, ease, and symmetry. A feel for light and ambience. An instinct for moments. Perhaps these are the very ingredients that define the photographic eye. In the works of these three men, we have an embodiment of the very same things.

Labels: dumaguete, film, negros, photography

[0] This is Where You Bite the Sandwich

GO TO OLDER POSTS

GO TO NEWER POSTS

3:29 AM |

The Three Virtuosos of the Photographic Eye

3:29 AM |

The Three Virtuosos of the Photographic Eye