Saturday, August 31, 2013

2:55 AM |

Kindness Will Always Be Remembered

2:55 AM |

Kindness Will Always Be Remembered

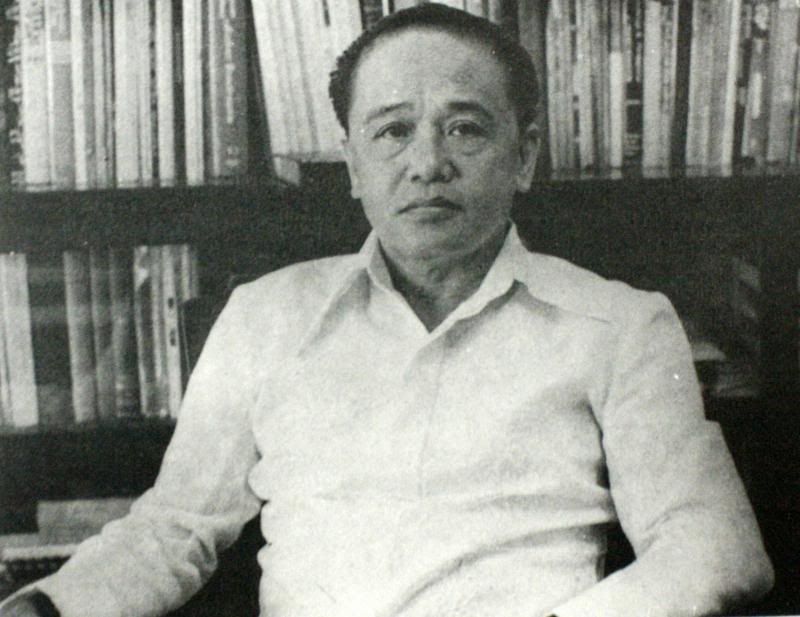

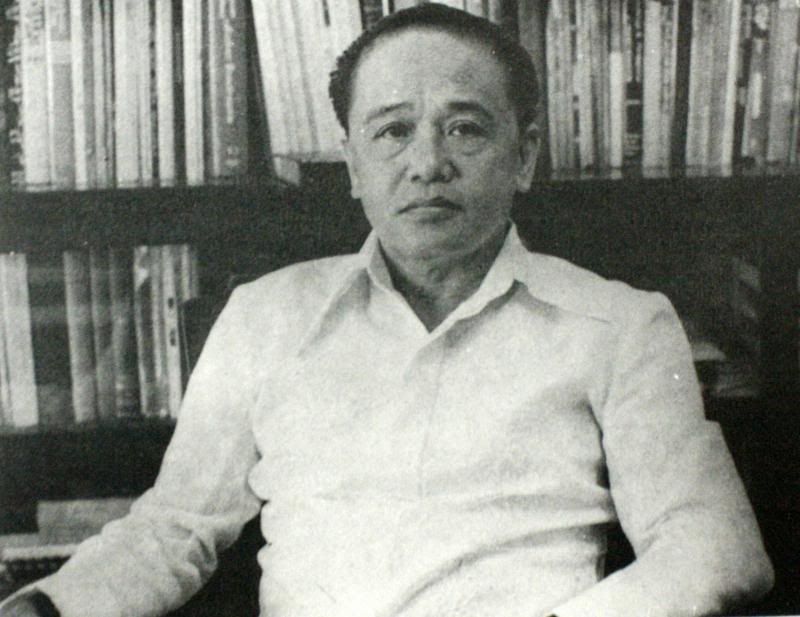

Like how most children know the friends of their fathers and mothers, I didn’t know much about Tito Proc, but I have known of him since childhood—and from my earliest memories of him, he has always struck me as a just man, one of the kindest I would ever know in this life.

I would learn later on that he was a close friend of the family because he had spent some time in the same Agusan del Norte town my father originated from, and from the stories he would tell me, they were fast friends. When my family finally came back to Negros Oriental to settle for good, first in Bayawan and later on in Dumaguete where I was born, Tito Proc—he was Cesing to many—had already become an important academic, and soon a major force in Silliman University. He would eventually serve the school for more than fifty years, the perfect picture of a true and loyal Sillimanian.

He was there in the audience, for some reason, when I had won some kind of contest in grade school, and I remember him taking me aside in one of those old classrooms in West City Elementary School, telling me that he was a good friend of my father’s, and that I should continue doing well with my studies, and that he expected me to matriculate in Silliman by the time I entered high school. He had said these things without a single trace of being patronizing. And from that day forward, I would think of him as a sincere man whose currency were kindness and a quiet kind of encouragement.

It didn’t sink in to me then that he was a man of importance: that he was a holder of Bachelor of Theology and Bachelor of Arts degrees from Silliman University and Central Methodist University, as well as graduate degrees from Union Seminary in New York, from Harvard University, and from San Francisco Seminary; that he was Acting President of Silliman during the first two years of Martial Law; or that he was its longest-serving University Pastor, from 1986 to 1999. I was a kid, and he was just “Tito Proc” to me.

In those days, when my family’s finances were particularly full of challenges, he insisted that everybody in my family should finish college in Silliman University, and wrote endless promisory notes in behalf of my brothers just in time for them to take their midterm or final exams. We were nomads then, making do of rented houses that were the very picture of humble living. We were quite poor, but we all eventually finished college in Silliman University, overcoming much in the process, and proving truly that education elevates the individual. I was luckier because I went through college when the family finally sailed through its darker days—but I’m not sure my elder brothers could have gotten the education they received were it not for good people like Tito Proc. And he was just “Tito Proc” all those years, somebody whose hands I made “mano” every time we’d visit his house in Amigo Subdivision.

When I finally came of age, it was with profound new respect that learned much of the man and his life. There are two stories I’ve come to know and made me admire Tito Proc more. One is of his tumultuous tenure as Acting President of Silliman University at a time when the entire country plunged into the darkness of Ferdinand Marcos’ martial rule. What a leader he must have been to be able to carry well, and with dignity and commanding presence, the concerns of Silliman and its students, faculty, and staff—even as the university got padlocked, and remained so for a stretch of time due to some notoriety as a hotbed of “radicals”—exactly the “scourge of society” Marcos was eager to root out and incarcerate.

Tito Proc negotiated for Silliman’s eventual reopening, while at the same time taking care to see to the needs of the faculty and students the military had picked up for interrogation and what-not. As Joel Tabada—the first Sillimanian faculty to be picked up by the military—once recounted to me, “Classes at the university were ‘suspended’ for the rest of the first semester. Dr. Udarbe became the acting president. But the experience made a man out of him as he faced the Martial Law people concerning the University. He ordered that double-deck beds from the Silliman dormitories be brought over and provided to the Provincial Jail for all the detainees, even if only about a third of the detainees were Sillimanians.”

Another story is something I learned from recent research we’ve done into the history of culture and the arts in Silliman, which we are doing for the Handulantaw coffee table book. (I am editor-in-chief, with the Tao Foundation and the Silliman University Cultural Affairs Committee as publishers.) When Tito Proc became Acting President, he inherited many of the projects that his predecessor, Dr. Cicero Calderon, was hoping to accomplish for the university.

One of these was Calderon’s grand ambition to build a Cultural Center in campus. Zara Marie Dy, writing about the Luce Auditorium for Handulantaw, wrote: “President Calderon recommended that a caretaker president be appointed for Silliman when he stepped down from the presidency. This president ad interim came in the person of Dr. Proceso U. Udarbe, whose term officially started on 1 June 1971. Acting President Udarbe was kept busy inaugurating and implementing the unfinished projects Dr. Calderon left behind. He raced to see the projects push through quickly in view of the inflationary trend of the times.

“One of his very first worries in 1971 was the delay in the construction of the Cultural Center. The funds had been promised back in 1968 by the Henry Luce Foundation of New York but the Cultural Center Planning Committee, composed mainly of the units which had their own interests in the Cultural Center, could not easily agree on space allocations, design and location of the Center, much less on the architect. The School of Music and Fine Arts, the Speech and Theatre Arts Department, the English Department, and Audio-Visual Department comprised the Committee, together with the Campus Planning Committee, chaired by the [dean] of the College of Engineering. This mix made for long meetings and stalemates.

“With financial exigencies weighing heavily against time, Dr. Udarbe decided to come to the helm and reorganize the Cultural Center Planning Committee. He became its chairman and steered it into agreement and action… By 28 August 1972, the groundbreaking ceremony for the Auditorium was held.”

These stories tell us what a strong leader Tito Proc was—a decisive visionary who knew when to act, and how to act.

As I write this, the news of his death has just broken out, right at the tail-end of Silliman University’s 112th Founders Day. May you rest in peace, Dr. Proceso U. Udarbe. Your kindness and your brand of leadership will always be remembered.

Labels: people, silliman

[0] This is Where You Bite the Sandwich

Saturday, August 17, 2013

So we did it again. Last August 12, we showed ten short films of varied appreciative levels—but nonetheless, together, they spoke volumes about how much we are trying to do to create a grassroots community of filmmakers in Dumaguete. Regardless of the challenges, of the risks, of the continuous possibility of being branded by others as “hopeless dreamers” without anywhere to go.

The roster that constituted

Dumaguete Shorts 2: A Festival of Short Films By New Dumaguete Filmmakers included

Ramon del Prado’s

I Am the Superhero from Tuldok Animation,

Melfred Casquite’s

Kalooy Man and

Francis James Kho and Carl Ivan Caballero’s

Asa from Foundation University,

Antonio Dago-oc’s

Josephine from Negros Oriental State University,

Mel Bermas Pal’s

Jeepney,

Jo Simone Vale’s

Ugma na Lang, and

Stephen Abanto’s

Have You Got Time for a Story? from Silliman University,

Razceljan Salvarita’s

Confession from Indie*Go ArtHub Films, and

Theodore Boborol’s

Ang Asawa Kong si Nikulet from Star Cinema ABS-CBN.

We began

Dumaguete Shorts two years ago to answer a challenge posed to us by the Cultural Center of the Philippines, when Teddy Co—the spirit behind

Cinema Rehiyon, the annual festival of films made from the regions—asked me during the Cinemalaya Congress in 2008: “Are there any films being produced in Dumaguete?” And my answer was a sad “No. Not really.” Of course, there were the rare efforts of Jonah Lim, but that was it: there was no such thing as a grassroots effort. Which is why we were in Audio-Visual Theater 1 in Silliman University last Monday night, to answer that question once with a a final and a resounding “Yes.”

Let me be clear, however. A few months ago,

some turk of a critic decried in a Mindanao website that what we are producing in Dumaguete are “failures” of cinema—which just shows how shortsighted he was about the efforts we are trying to do here. I’ve always understood something fundamental about the making of art: to get to the brilliance of the diamond, you have to contend with the cuts you have to make to tease out its luster, its brilliance.

And that’s what we have been doing in

Dumaguete Shorts 2—encouraging local efforts of filmmaking, just to make a start. It is always better to start with something than with nothing. And soon enough, we will have filmmakers who are more daring in their themes, and brilliant in their uses of their language of cinema. Many of the films we have seen are the efforts of students from the universities of Dumaguete—from NORSU, Silliman, and Foundation, each of which has its own short film contests, and last Monday we saw many of the products of those competitions held during the past year, augmented by titles by independent filmmakers. All of these truly make this short film festival a melting pot of our local cinematic efforts.

Labels: dumaguete, film, foundation, indiehub, negros, norsu, silliman, star cinema, tuldok

[0] This is Where You Bite the Sandwich

5:48 PM |

The Birds of Julia, The Flowers of Susan

5:48 PM |

The Birds of Julia, The Flowers of Susan

Last Friday afternoon, we saw the opening of a twin painting exhibit by two members of the otherwise musical Vista family. The exhibit, titled

Birds & Flowers, is exactly that—a show of paintings in acrylic and in watercolor of birds and flowers, the favorite subjects of our two visual artists.

Elizabeth Susan Vista-Suarez has always been known for the music that she makes, be it as director of the Silliman University Campus Choristers in one of its heydays in the 1990s, or as current director of Ating Pamana and the Silliman University Gratitude and Goodwill Ambassadors, or as dean of the College of Performing and Visual Arts.

A few years ago, however, she started dabbling in an art form completely different from her usual discipline—painting. But it was also something that has much in resonance with her musical personality: to daub colors, to select texture, to blend light and dark, to compose the visual—all of that is familiar to the best of musicians, if only done in a different terrain. She started painting in oil, and later changed to acrylic when her painting mentor told her the medium was healthier for her.

It was a surprising turn of interest, given that she has had no influences in painting—only that she liked the works of the Impressionists, and has always had a love for the gracefulness of Asian art. But perhaps that proclivity for the visual has already some stirrings in childhood. “In high school, I’ve already been making flowers in that Chinese painting method, which I’d do on stationery, with watercolor. I did it to sell to my aunties,” she says. “But I became more interested in painting when I went a bit blind at the age of forty. I needed to see color again, afraid that I might not be able to see anything at all. But painting has helped me be in my own world, where I can turn my ears off amidst everyone and everything.”

But what is it about flowers that attracts her most as subject for her paintings? “Flowers are the easiest to paint,” she says. “And flowers also symbolize strength and beauty. They are just like women—they’re often abused, and kicked around in a very patriarchal world. I remember the lyrics of this song that goes: ‘Little flowers never worry when the rain begins to blow, and they never cry when the rain begins to pour… Though it’s wet and cold, soon the sun will shine again, and they’ll smile unto the world for their beauty to behold!’”

Her underlying aesthetic philosophy for her paintings is simple enough: it is an expression of a personal joy. “And joy equals no expectation,” she says. “When we do our best, God will do the rest.”

Julia Christine Vista Zamar—Justine to friends, and Tatin for those us who watched grow up in Vista Cottage in Silliman campus—on the other hand, have always known that there was enormous power in the act of taking up the brush and rendering the world through painting.

That realization began to sink into her consciousness when she would watch her mother work on her flower paintings. “My mom has always been my influence,” she says. “She has been painting for some time now, and often when she paints, I’d get to sit around and hang with her and watch her do her painting. In those times, I’d always see that she finds joy in painting. It also calms her—it was more like a stress-buster soothing system for her. And having seen that many times in my life, I thought that maybe some day I’d like to try what she’s doing.”

But there was no definite start for her when it came to finally doing painting. One thing she could remember growing up, however, was borrowing her mother’s fabric paint and doing little doodles on katcha—and give them as gifts to friends. “I didn’t really imagine myself doing a whole painting but when a good friend of mine asked me to join Hersley-Ven Casero’s Collaborative Project, I took it as a challenge to finally paint a whole picture,” she says. “After that, I was starting to explore more about painting, and finding out how interesting and fun it can be. This is an entirely new sense of self-discovery.” She began to use watercolor. It was the medium she was the most comfortable with.

But what is it about birds that has attracted her as subject for her paintings? “Birds are one of the most interesting creatures,” she says. “They are among the smartest animals ever created, even smarter than dogs. But the one thing about birds which I love the most is how symbolic these animals are. They remind me of hope.”

She sees her watercolor paintings as a statement she is making about never limiting oneself. “Sometimes we think that mixing different colors would give a horrible effect on a painting,” she explains, “but when you actually try different things without fear, you’ll realize that something beautiful will come out of it.”

“Still, I don’t really know what’s going to happen in the future with my paintings,” she continues. “But I do hope that somewhere in the future, they’d be hanging on walls in different places of the country. But birds will always be my main subjects, although it would be interesting to try to paint people and use acrylic as medium.”

Labels: art and culture, cultural affairs committee, dumaguete, negros, painting, silliman

[0] This is Where You Bite the Sandwich

Saturday, August 03, 2013

7:38 PM |

Throwing Off the Philistines

7:38 PM |

Throwing Off the Philistines

“Without culture, and the relative freedom it implies, society, even when perfect, is but a jungle. This is why any authentic creation is a gift to the future.”

~

Albert Camus

To understand the passions of the artist, one needs only to take a look at Dessa Quesada-Palm. Consummate theater actress and tireless community activist—as founder of Youth Advocates Through Theater Arts or YATTA, she uses community theater as instrument to further causes such as gender sensitivity and the environment—she has epitomized for me, and for the longest time, the selflessness of a person who believes in cultural work and its importance in community life.

Since May, we had worked together to fulfill director Amiel Leonardia’s vision for Elsa Martinez Coscolluela’s

In My Father’s House. She played my mother Amanda, and in the course of six weeks devoted to the strictest of rehearsals, I saw firsthand how she worked to get her part right. What she showed me and the rest of the cast was a master class in acting. Part of that revelation was a model for professionalism that went into it, and a dedication that necessitated sweat and sacrifice.

In the end she did command the Luce stage like the strong actress that she was—but we also knew how generous she was in sharing the stage with us amateur actors: how she reminded us of our cues with the slightest of glances that she gave us, the subtlest gestures that she made in our direction, enough for us to be prompted when necessary. And yet, all throughout those intense months of rehearsals, she still managed to go about her work as a cultural worker, giving workshops everywhere in Negros, and teaching her Directing class at the theater department of the College of Performing and Visual Arts in Silliman University…

Earnest Hope Tinambacan, who played my brother Franco, is also the same: he, too, had workshops to do—his bread and butter—aside from the fact that he also had his music to take care of, being the front man and composer for HOPIA, a local band that is increasingly making waves in local music. Two weeks before we had to debut at the Luce Auditorium, he also had to stage a huge concert that blocked off the whole stretch of Silliman Avenue from Rizal Boulevard to Hibbard Avenue, an event he pulled off with other Dumaguete bands—to showcase, of course, the release of their compilation CD, The

Bell Tower Project. In his spare moments, tucked in the wild schedule that was the bane of our existence, he’d squirrel away to memorize his kilometric lines for the play. In the end, he embodied Franco with a finesse that was startling—sending many in the audiences we had to tear up. In the 3 PM matinee of our last day of performances, the high school students who were our audience for that show went en masse to the side entrance of the Luce, demanding to see their “new idol.” The shouts of “Franco! Franco!” was a heartening sound to listen to.

In Dumaguete, you can find many other people exactly like Dessa and Hope—extremely gifted artists with extremely busy schedules, and yet they are still able to do something concrete for the community just for the sake of elevating culture and the arts. There’s Razceljan Salvarita. There’s Hersley Ven Casero and Anna Koosman. There’s Whitney Fleming. There’s Arlene Delloso-Uypitching and Annabelle Lee-Adriano. There’s Virginia Stack and her Valencia troop that would include Larissa Gutch, Jaruvic Rafols, RV Escatron, and Aaron Jalalon. There’s Joseph Basa. There’s Ramon del Prado. There’s Moses Joshua Atega. There’s Leo Mamicpic. There’s Diomar Abrio. There’s Elizabeth Susan Vista-Suarez, and so many more.

But they all know, like I do, that the work of culture is often both frustrating and rewarding. And sometimes, the frustration can start to break our spirits—if only temporarily. Once, while doing an Arts Month event with Dessa a few years ago, I turned to her and with such despair in my voice: “Why do we do this? Cultural work can be such a thankless job.” She turned to me and said, “Because despite everything else, we love what we do—and we cannot help but share it with everybody else.”

She was right. Theater producer Hendrison Go said as much to me last month when he said, “You may say you’re stressed out—but you do this anyway because you know it makes you happy.” He’s also right.

I am particularly happy that I work with kindred spirits in the Cultural Affairs Committee of Silliman University. Under Diomar Abrio’s savvy leadership, and with keen support from our university president, the CAC has worked hard for so many years to put a semblance of structure and balance to the cultural life of the university and the city. The committee turns 51 years old this year, and already it has brought in so many significant cultural milestones to Dumaguete—so much so that we can verily call this city as the real cultural center of Southern Philippines.

But like most things, it has its highs and it has its lows. When we decided to reboot how culture was being done about six years ago, we took in something that was more or less shapeless, and gave it structure. This is how our “cultural seasons” came into being: to give the university a workable cultural calendar, which at the same affirms culture and informs people about the things we are doing in the university. We are still learning how to promote culture and the arts properly, but at least we have made a start.

I always tell my students that they are lucky to be in Silliman because they get this cultural programming during their entire college stay, which will certainly inform their education, and finally the way they will conduct things in the real world. (And under a subsidy, too! Which means they get culture in an affordable way. No other university in the Philippines does this—and so they get the best of culture, locally, nationally, and internationally, for a pittance almost.)

But students being students, they do think this comes under the thankless maneuver of things “required,” which is something they are loathe to do because…I don’t know, it takes time away from their DOTA and their Internet surfing? But many of us persevere anyway. And then I do get many emails from former students, finally thanking me for “forcing” them to watch all those shows when they were younger. I guess the impact of cultural education in their real lives only get manifested much later on. (They say, for example, how many of their co-workers in the Real World are basically culture-deprived, ignorant. “Thank God I went to Silliman,” they’d tell me.)

We’ve been doing well at the CAC, more or less. Things could always be better, of course, but alas most people—even the best and brightest of the city—think culture is something to be largely ignored because it is “unimportant.” It is the least in their hierarchy of “necessary things.” It becomes a constant struggle every year to convince people of the otherwise. Every year, the CAC tries to balance all the arts—literature, music, dance, theater, the visual arts—in our programming, and most of the time, we do get the best for our efforts. And people have indeed been responding more positively to our efforts year after year.

Culture’s a hard job, but somebody’s got to do it.

Labels: art and culture, dumaguete, life, music, silliman, theater

[0] This is Where You Bite the Sandwich

GO TO OLDER POSTS

GO TO NEWER POSTS

2:55 AM |

Kindness Will Always Be Remembered

2:55 AM |

Kindness Will Always Be Remembered

6:00 PM |

Shorts!

6:00 PM |

Shorts!

5:48 PM |

The Birds of Julia, The Flowers of Susan

5:48 PM |

The Birds of Julia, The Flowers of Susan

7:38 PM |

Throwing Off the Philistines

7:38 PM |

Throwing Off the Philistines