Thursday, April 30, 2015

9:02 PM |

And Here I Am...

9:02 PM |

And Here I Am...

Labels: life

[0] This is Where You Bite the Sandwich

Wednesday, April 29, 2015

1:39 PM |

Headline News Blooper

1:39 PM |

Headline News Blooper

I get why this happens. It has happened before. What most people don't get is that, unlike TV or radio or the Internet where breaking news can happen, newspapers are physical objects in need of systematic circulation that need

specific deadlines to run -- and if you are a national newspaper, that's a lot of circulation to consider.

If a story is imminent, newspapers make a template of what could possibly happen, run with it, and hope for the best. (Major newspapers, for example, have an active obituary staff who write every important persons' obituaries, with constant updates, long before these people are dead. So that when death does come, the writers just fill in the blanks regarding the specifics -- and

voila, instant publication only minutes after the announcement.) It is all done in the name of scoop and/or timeliness.

This is not a story of bad journalism. This is a story of how one medium of news may no longer be suitable for the times we are living in. Most of the time, editorial hunches for imminent news stories are correct -- but sometimes it does spell disaster, like the famous

"Dewey Defeats Truman" headline of

Chicago Tribune in 1948. Shouting "Stop the press!" happens only in movies. (But I do wish these newspapers have the prescience of that newspaper in the film

Chicago. In that scene near the end, the newsboys await the verdict for Roxie Hart's murder charge, with two headlines ready for the selling: "Guilty!" says one version, "Innocent!" says another. They get the proper go-signal from the courthouse -- and one version of the newspaper vanishes instantly into the truck. But this happens only in movies.

To quote the great Alain de Botton in

The News: A User's Manual: "... The stories we take in were decided not by supernatural decree after a conclave of angels but by a group of usually rather weary and pressured editors struggling to assemble a plausible list of items in harried meetings in corner offices over muffins and coffee. Their headlines don't constitute an ultimate account of reality so much as some first hunches as to what might matter by mortals prey to the same prejudices, errors and frailties as the rest of us, hunches plucked out of a pool of several billion potential events that daily befall our species."

Which makes me think: in the age of instant gratification, news do run better now in social media (

where errors are necessarily less forgivable), especially if you need your news like you need your instant coffee. Newspapers may not be dead yet (and I hope they don't die off like the dinosaurs), but as a medium of news in the age of breaking news via Twitter, it is truly showing its creaky joints.

Photo from Coconuts ManilaLabels: issues, journalism, news

[2] This is Where You Bite the Sandwich

Tuesday, April 28, 2015

1:19 PM |

Hit Me With Your Best Shot: Jane Campion's Bright Star (2009)

1:19 PM |

Hit Me With Your Best Shot: Jane Campion's Bright Star (2009)

I started this film looking for one thing, but like with many experiences in pursuit of something, I found another thing.

A film about the romance between John Keats and Fanny Brawne invites a certain reading, a writerly one. Of these films, we ask the hoary questions:

how does one live a poetic life, what exactly goes into the making of poetry, and what inspires it? But capturing the dynamism of a writerly life in film has always been an exercise fraught with near-misses, although one can argue about a strong tradition of literary biographies and fictionalised renderings of real lives in celluloid, from

Henry & June to

Agatha to

The Basketball Diaries to

Capote to

The Hours to

The Last Station, as well as well-meaning mishaps like

Becoming Jane and

Anonymous. The writer as a character in film has always been a fascinating subject. In this trope, we are presented the life of the mind via a creative person, someone also bedevilled by neuroses that feed that creativity.

Drama ensues. When the writer happens to be real, the fascination becomes even deeper.

But how does one exactly convey the life of the mind? Being a writer is primarily that -- an existence of solitary grappling with the word, locked in an imagined tango with the quest to craft the perfectly turned out phrase. Sometimes a film about a writer is successful only in conveying the more dramatic environment of

being a writer

in the world -- consider, for example, the wild jaunts of Leonardo Di Caprio's brash and young poet in

Total Eclipse, or the confining interior world of Michael Douglas' troubled novelist in

Wonder Boys -- but

not the

act of writing itself. Understandably so: there is nothing cinematic in capturing the act of scribbling or writing or typing on a keyboard. Filmmakers employ techniques, of course, to cheat some cinematic drama into the act of writing -- for example, using emotive voice overs reading well-known lines from a literary text while the camera gracefully captures a writer's penmanship -- but the visual shorthand has become a cliche, and a hollow one. Perhaps the best cinematic attempt in capturing the writer and his work-in-progress is Jeffrey Friedman and Rob Epstein's

Howl (2010), their fascinating if imperfect dramatisation of Allen Ginsburg's celebrated poem and the scandal that followed the wake of its publication. It is a miraculous film in that it managed to cinematically render authorship, craft, and literary criticism -- a worthy experiment in film narrative that did not quite become a success, but can be lauded for its bravery for trying to capture a veritable lighting in a bottle.

And then here comes Jane Campion's

Bright Star. It is perhaps the most accessible of all of her films, after the enigmatic feminism of

The Piano, Portrait of a Lady, In the Cut, and her television show

Top of the Lake. Part of the reason for its accessibility is the consuming richness of its cinematography: almost every scene in it is an act of careful composition done in weathered beauty, but nothing too contrived to make the look lifeless. There is, in fact, an organic feel to the beauty of the film's images -- and I think it is an aesthetic choice Ms. Campion made to underline the thing she wants to explore in this story about the Romantic poet and his muse.

I was tempted to scour this movie for images that would help me mark it as a worthy exercise in showing us the cinematic possibilities in the literary life. And for sure, there are instances of that...

Like this frame of a solitary Keats writing a poem in the middle of an orchard, which for me is the perfect picture of writerly contemplation, his uncomfortable position in that chair a shorthand for the hardship of crafting...

Then there is this shot of Fanny Brawne writing a letter to the poet, the very act of writing interposed on the image to give us an idea that this is a film, after all, about writing and inspiration...

But this thought struck me suddenly: don't look at this film as a literary biography, or an examination of literary life. Look at it for the emotions it trumpets. And then I realised that the titular character may be Fanny Brawne, fashionista and muse, but it is not her that the film fusses over. She is

not its object of affection. She is not the receiver of our gaze, the object of all that longing the film revels in. The movie may be about poets and poetry and the love lives they often figure in, but it is ultimately about longing and pining. Fanny Brawne is the ultimate actor of these tendencies. The film is about her...

... looking at him, Keats, with the pure adoration of the besotted.

How the film lingers on the poet's face. Lovingly, like a caress.

This is my best shot. Here is Ben Whishaw's John Keats receiving his own loving, lingering Joseph Fiennes moment in

Shakespeare in Love -- the object of a tender female gaze.

Like Abbie Cornish's Brawne, Gwyneth Paltrow's Viola De Lesseps in John Madden's comic 1998 masterpiece about Shakespeare's loves and torments may have been offered as the muse from which our literary genius had wrought great works. But the two films subtly make the case that these men, too, are muses for the women.

These shots -- from the muses' points of view -- eagerly ask us to partake of Fanny and Viola's gazes.

Look at them, they dare us.

Swoon.

This post is part of Nathaniel Rogers' Hit Me With Your Best Shot series over at The Film Experience blog.Labels: film, love, poetry, writers

[0] This is Where You Bite the Sandwich

Monday, April 27, 2015

5:20 PM |

Gracefully, Melodramatically

5:20 PM |

Gracefully, Melodramatically

Now that I have seen Olivier Dahan's

Grace of Monaco (2014), I find most curious the

superstorm of criticism that greeted its opening in various cities in Europe after it made its debut at Cannes. (It never did open in the U.S.,

consigned to television fare by a distributor seeking retribution against the director.) Turgid, flat, vapid, and excruciating are some of the "nicer" epithets hurled against this heavily fictionalised biography of Grace Kelly, the supreme ice queen of classic Hollywood cinema turned real-life princess. Because, as played by Nicole Kidman, the royal portrayal is a performance that is very much a sleight-of-hand: we know that it cannot be a spot-on take --

how do you that, when Grace Kelly's very image is burned so hard on our collective pop consciousness? -- but Ms. Kidman does an impersonation that is more than fitting for the requirements of the material: beautiful princess finds herself in the maelstrom of a pseudo-thriller filled with political machinations, all touched by the elusive glamour of cinema and royalty. I liked the film. I did not love it, but it is far from the disgrace critics make it out to be. Truth to tell,

Grace of Monaco is actually a better film than

La Vie en Rose, Dahan's previous effort at exploring the exquisite travails of a female icon, in that case the trouble-addled life of French singer Edith Piaf. That other film, while strongly anchored by the sheer brilliance of Marion Cotillard, floundered around looking for a structure.

Grace of Monaco, on the other hand, is all structure, and replete with performances that don't register false notes, contrary to what the critics say. It's only problem perhaps is in trying to drum up dressed up drama and shimmering intrigue over the humdrum, something perfectly encapsulated by the whole sequence of Princess Grace arriving at Monte Carlo for the Red Cross Ball, using star power to counter international political shenanigans.

In an

essay for the British Film Institute website, Brad Stevens said as much:

In general, popular movies aimed at female audiences are evaluated more harshly than those aimed at male audiences, and when royalty is thrown into the mix, the response tends to be particularly virulent: witness the critical contempt which greeted Oliver Hirschbiegel’s Diana (2013) and Madonna’s W.E. (2010).

Yet this contempt has little to do with strongly held republican values. Tom Hooper’s The King’s Speech (2010) was treated respectfully even by detractors, despite its being the most glibly reactionary entry in the recent royal cycle; the scene in which King George VI (Colin Firth) recalls how his nanny refused to feed him suggests that, seen from the ‘correct’ perspective, the working-class female employee is actually a powerful tyrant, the privileged male aristocrat really just another starving peasant.

The reason The King’s Speech was acclaimed and Grace of Monaco jeered surely has something to do with a lingering intellectual distrust of melodrama. Although a great deal of serious theoretical work has been devoted to this genre, the rhetorical gestures associated with it still tend to disturb middlebrow reviewers (as, indeed, they should), particularly when encountered in a context that is neither sealed in a historical vacuum (classical Hollywood is an object for study, and thus can no longer trouble us), nor heavily marked by signifiers of ironic distance (see, for example, Todd Haynes’s Far from Heaven) motivated by a specious misreading of Sirkian irony, which is incorrectly seen as precluding emotional involvement.

An elegant use of sincerity and the kowtowing to melodrama, Stevens contends, constitute the very crime committed by Dahan's film. I find that critical absolute repugnant.

Who mandated the privilege enjoyed by irony and restraint? (Uhm, male critics, for the most part.) These two stylistic uses contribute to an effect critics usually call "muscular storytelling" -- indicating a bias towards manlier stories, relegating to the wayside feminine concerns and feminine expression.

This is why directors like Nora Ephron or Susan Seidelman or Jane Campion often struggle with critical acceptance for their starkly female projects, garnering praise for singular works (

Sleepless in Seattle, Desperately Seeking Susan, and

The Piano) during rare years when the critical consensus feels the necessity to do token appreciation for female work. (They don't get the same critical love afterwards, their efforts chided away for being too difficult, or too unimportant.) The only unmitigated success by a female filmmaker is one demonstrated by Kathryn Bigelow, who barrelled to Oscar recognition for a work that is undeniably masculine in

The Hurt Locker.

The sad truth is, we never really give much space or respect to what female artists have to say. They are always boxed in. Meghan Murphy in

Women and Girls Don’t Need to Be Told to Be Nicer sums up this problem this way: “The trouble is that, for women, being 'nice' often translates into putting up with things we should never put up with... We smile when we’re harassed on the street or hit on by jerks. We laugh at sexist jokes. We learn that when we have strong opinions, we’ll be called bitches and that if we get angry, we’ll be called hysterical. When we say what we want, we’re called pushy or aggressive. Part of learning 'ladylike' behavior is about learning to smile politely when someone is being crude. Femininity has long been attached to passivity and to being docile. Men fight, women giggle and fume silently.”

Princess Grace fights in Dahan's film, and speaks out wilfully, gracefully. The critical consensus has shut her up by declaring the dramatisation of that as "vapid."

Labels: feminism, film, issues, life

[0] This is Where You Bite the Sandwich

Sunday, April 26, 2015

7:41 PM |

Gladys Glover and the Celebrity of Being Kim Kardashian

7:41 PM |

Gladys Glover and the Celebrity of Being Kim Kardashian

To understand Kim Kardashian, Paris Hilton, and the whole puzzling fact of becoming celebrities for having accomplished particularly

nothing, one has to go back to the 1954 Judy Holliday comedy titled

It Should Happen to You, directed with wit and panache by George Cukor. It is perhaps the first film to explore seriously the phenomenon of Becoming Famous for Being Famous.

In this forgotten Hollywood gem -- it is notable for being the first film to star Jack Lemmon -- a down-and-out former girdle model played by Ms. Holliday commiserates about not having made a name for herself in New York, despite having lived in the city for two years. She laments that all she has to show for it is $1,000 that she managed to save up. Lemmon's character, an intrepid documentary filmmaker who slowly falls for her, tells her: "Well, when there's a way, there's a will" -- and soon she gets inspired to rent out a billboard in Columbus Circle, bearing just her name,

Gladys Glover.

She rents the sign for three months, and circumstances in the film involving Peter Lawford's character and the soap company he runs soon multiplies that one billboard sign to six, spread all over Manhattan. And soon people starts asking, "Who is Gladys Glover?" A TV presenter editorialises that she is probably just the second cousin of Kilroy (

hahaha, I like that line) -- which our Ms. Glover promptly corrects of course, and soon she is making guest appearances on television and becomes a full-fledged model. And soon she really becomes famous for just being famous.

There is one scene in the movie shared by Gladys and Lemmon's Jack Sheppard that grapples the common misgivings about the phenomenon. They are having dinner, and Jack tries to show her how foolhardy she has been with her obsession for getting her name out there...

Jack:

Jack: What's the point of it? Where's it getting you? No place.

Gladys: No place? I started out with no signs, so then I got one sign... so then I get six. So where do you get "no place"?

Jack: I don't know what it is, honey, but I don't seem to get through to you. Let me put it this way. What most people, real people, want is privacy. That's about the best thing anybody can have.

Gladys: Not me.

Jack: What is this craze to get well-known?

Gladys: Why craze?

Jack: Do you think everybody is so anxious to be above the crowd?

Gladys: Yes.

Jack: But what's the point of it? (

Beat.) In the first place, everybody can't be above the crowd, can they?

Gladys: No. But everybody can try if they want to.

Jack: But why isn't it more important to learn how to be a part of the crowd?

Gladys: Not me.

Jack: It isn't just making a name. Don't you understand that? It's making a name that stands for something. Different names stand for different things.

Gladys: So who said not?

Jack: You want my opinion?

Gladys: No...

Jack: My opinion is this. It's better if your name stands for something on one block than if it stands for nothing all over the entire world.

Gladys: I don't follow your point.

Jack: I sure wish you could...

And for some reason -- and I can't believe I am doing this -- I agree with Gladys, and to a degree, Kim Kardashian and her ilk. Why would you want to stop anybody from achieving their dream of being famous and be a success at it, and who are we to judge the means with which they pursue it as being less valid? What does "having accomplished nothing" really mean? And really, if there is a way, shouldn't there be a will? During one of Glady's television appearances, a viewer at a bar tells another one: "All she's got is nerve, far as I can see..." The other one says: "Maybe that's all you need nowadays. Four programs in one week. She's certainly making a name for herself."

And that's that.

[0] This is Where You Bite the Sandwich

Friday, April 24, 2015

10:23 PM |

Not Mine Anymore

10:23 PM |

Not Mine Anymore

I was reading

The Paris Review's

The Art of Fiction interview with the great fictionist and Nobel Prize laureate

Alice Munro, and this quote from her got to me and made me think, and made realise...

...everything is all right in the world.

Labels: life, literature, quotes, writers

[0] This is Where You Bite the Sandwich

Wednesday, April 22, 2015

1:42 AM |

Hit Me With Your Best Shot: Colin Higgins' 9 to 5 (1980)

1:42 AM |

Hit Me With Your Best Shot: Colin Higgins' 9 to 5 (1980)

I didn't particularly like Colin Higgins'

9 to 5 (1980) when I first saw it on VHS two decades ago, although I pretty much got what it wanted to accomplish:

be a silly pseudo-feminist romp that's nothing more than cornball and a half, plus a catchy song. Based on an idea by co-star Jane Fonda, the film could be considered as the pathbreaking comedic turn to a string of films (

Klute, Julia, The China Syndrome, The Electric Horseman) grounded by her famous feminist persona in the 1970s, an outspoken activism which earned her, among others, the nickname Hanoi Jane. Here, Ms. Fonda finally plays it mousy --

at first. And then we get the old persona back, a pastel version of it that allows her to mock and affirm her reputation at the same time. (Then again, one could also make a case of Ms. Fonda's evolving female personality through the decades -- from the quirky doll of the 1960s to the tough woman of the 1970s to the aerobics queen of the 1980s. That's a lot of shifts in public persona.)

The film, of course, was a tremendous success when it came out, and it continues to be in circulation, attesting to its longevity in pop culture. I'm not sure if the subject matter -- three office women connive on the comeuppance of a chauvinist pig boss -- have much to do with the film having legs (

oops!), and for me, the ultimate magic that explains it is the easy chemistry of its cast, which explains its continuing significance. There's nothing much to this picture but Jane Fonda, Lily Tomlin, and Dolly Parton (and yes, Dabney Coleman) deliver sharp comic performances that are easy on the uptake, grounding their caricaturish characters with some fierce actorly gravity. We might as well crown the film as having given birth to a much-beloved (

by me) comedic subgenre of "women taking revenge upon the men who wronged them," into which belongs such fun highlights (most of them starring Bette Midler) as

The First Wives Club,

She-Devil, and

Outrageous Fortune. And, fine,

The Other Woman.

But it's really just a silly romp, much of it a prolonged series of revenge fantasies that have not aged well. Consider Jane Fonda's hunting fantasies...

Or Dolly Parton's reverse sexual harassment fantasies that end with some strange cowgirlish wrangling...

Or Lily Tomlin's Snow White and a cup of rat poison fantasies...

There is a dated feel to these notions that almost mars the beautiful simplicity of the movie and shunts what ounce of feminism lite it has -- but then again I'm reading this with a 2015 consciousness on gender issues that may be the wrong framework to understand the humour of a 1980 film.

So okay, then. What is my best shot? This one.

It's the fairy tale shot of all three female protagonists at the end of that prolonged revenge fantasy sequence, quickly reminding us not to take all these too seriously. It's just a band of modern princesses (decked in medieval wear) wanting their much-earned day in the sun, waving their hands from a castle they deserve to live in, away from the men who cannot even begin to give them their worth. It's a sweet shot, gauzy and in pastel. We smile, and we say, "Go, girls!" And we enjoy the film for its magnificently staged wackiness, and get a small pinkish twitch of enlightenment about gender equality.

This post is part of Nathaniel Rogers' Hit Me With Your Best Shot series over at The Film Experience blog.Labels: film

[0] This is Where You Bite the Sandwich

Tuesday, April 21, 2015

12:16 AM |

"You Will Grow to Love Me Less and Less..."

12:16 AM |

"You Will Grow to Love Me Less and Less..."

Life can sometimes feel like an aspect ratio of 1:1, and then there are days when everything feels like 2.35:1 and in Technicolor. Watching Xavier Dolan's

Mommy (2014), and feeling sucker-punched.

Steve Després: We still love each other, right?

Diane Després: That's what we're best at, buddy.

Sob.Labels: film, life

[0] This is Where You Bite the Sandwich

Tuesday, April 14, 2015

9:06 PM |

How to Write the Big Issue

9:06 PM |

How to Write the Big Issue

"The bigger the issue, the smaller you write. Remember that. You don't write about the horrors of war. No. You write about a kid's burnt socks lying on the road. You pick the smallest manageable part of the big thing, and you work off the resonance."

~ Richard Price

Labels: quotes, writing

[0] This is Where You Bite the Sandwich

Monday, April 13, 2015

This is Hendrick Van Anthonissen’s

Beach Scene, before and after the uncovering of its pentimento. I've always loved the idea of

pentimento, which means "to repent" -- and in art encompasses painterly corrections or a changing of the mind in the creative process, which expose previous versions of the design. I remember this quote from

Pentimento by Lillian Hellman: “Old paint on a canvas, as it ages, sometimes becomes transparent. When that happens it is possible, in some pictures, to see the original lines: a tree will show through a woman's dress, a child makes way for a dog, a large boat is no longer on an open sea. That is called pentimento because the painter 'repented,' changed his mind. Perhaps it would be as well to say that the old conception, replaced by a later choice, is a way of seeing and then seeing again. That is all I mean about the people in this book. The paint has aged and I wanted to see what was there for me once, what is there for me now.”

People come and go in our lives, leaving traces.

Labels: art and culture, life, painting

[0] This is Where You Bite the Sandwich

1:48 AM |

Alone is Not Lonely

1:48 AM |

Alone is Not Lonely

Hiromasa Yonebayashi's

When Marnie Was There (2014) -- which might be the last offering we get from legendary Studio Ghibli, which has announced a "temporary" stoppage to film production -- is a wonderful, albeit small, film. It is a dialling back from the epic reaches of Hayao Miyazaki's

The Wind Rises (2013) and Isao Takahata's

The Tale of Princess Kaguya (2013), and which actually has much in common, spiritually speaking, with Takahata's

Only Yesterday (1991).

Like that film, we follow a female protagonist in an almost accidental search for self in serene, laid-back Japanese countryside. In

Marnie's case, however, we get not a mature woman but a socially awkward pubescent orphan named Anna, who would rather be alone and draw in her sketch book than deal with the curious interactions of other people. Life for Anna is compromised and painful, but then she meets Marnie in a seemingly abandoned mansion by the marsh. The blond young girl is gregarious and enchanting, and becomes Anna's first real friend -- but is she real, or is she a ghost? Or worse, is she merely the imagined projection of Anna's tortured wishes for a connection?

There are all these twists in the plot, borrowed from the book by Joan G. Robinson, but the whimsy of their unfolding, while interesting and beautifully rendered in animation in that signature Studio Ghibli eye for sparkling detail and minute movements, is not what hooked me.

I was prepared to pronounce this as Studio Ghibli's subtle nod towards queer representation -- the relationship between Anna and Marnie skirts towards levels of intimacy that cannot be just friendship -- but its final turn somehow nullifies that possible reading, much to my disappointment. As is, the film's choices and conclusion become too much of a comfortable cliche in terms of a narrative twist. But then again we cannot fault a film for not becoming what it does not set out to be.

But I like the film. I like its quiet moments, those scenes where Anna longs to get lost in the woods or in the middle of a lake, with only herself as company. It reminded me of my own childhood, where my nightmares were all about having to deal with other people, and the true antidote to all that sociable connecteness was being alone, entertaining myself with my little games, or reading, or sketching the afternoons away in a kind of daydream. Being alone was less lonely than being in the middle of a crowd. I was Anna.

Labels: cartoons, film, life

[0] This is Where You Bite the Sandwich

Sunday, April 12, 2015

8:21 PM |

Hit Me With Your Best Shot: Martin Scorsese's Taxi Driver (1976)

8:21 PM |

Hit Me With Your Best Shot: Martin Scorsese's Taxi Driver (1976)

The thing about iconic films is that the best of their images are burned so deeply into our collective pop cultural memory that to choose a "best shot" to define our appreciation of them is an exercise fraught with peril, because the shots we do love -- Janet Leigh's dead eyes segueing from the shower drainage in

Psycho, Julie Andrews making that first twirl in the hills in

The Sound of Music, Tom Cruise hanging from that wire in the first

Mission: Impossible -- make the very act of choosing them an exercise in cliche.

Martin Scorsese's

Taxi Driver (1976), lensed with pulsating savagery by Michael Chapman, is one of those films. Think about it.

There's Travis Bickle preening before a mirror, asking "Are you talking to me?" There's Travis in a mohawk with fingers laced with blood. There's Travis taking Betsy out on a date in a porn theatre. There's Travis and Iris in that suffocating room where she takes her tricks. There's Travis and Sport in that final orgy of killings. All these in a burst of concentrated energy weaved together with slithering skill by Tom Rolf and Melvin Shapiro. (Thelma Schoonmaker would officially become Scorsese's go-to film editor starting in 1980 with

Raging Bull.)

But the film above all is an examination of New York as the very embodiment of hell on earth, with Robert de Niro's character being a psychotic and self-righteous adventurer through the city's fiery highways, essentially playing Charon to its sinful denizens.

Which is why the film's first image serves well as the perfect introduction (and short hand) to its themes: here's a taxi weaving through hellish city smoke, itself tinged with the fiery red of the city's neon lights. It says, "Welcome to hell, and this is your ride."

It is my best shot for a film that is replete with so many best shots.

This post is part of Nathaniel Rogers' Hit Me With Your Best Shot series over at The Film Experience blog.

This post is part of Nathaniel Rogers' Hit Me With Your Best Shot series over at The Film Experience blog.Labels: film

[0] This is Where You Bite the Sandwich

10:00 AM |

A Studio Ghibli's Completist List

10:00 AM |

A Studio Ghibli's Completist List

UPDATE: STATUS COMPLETED

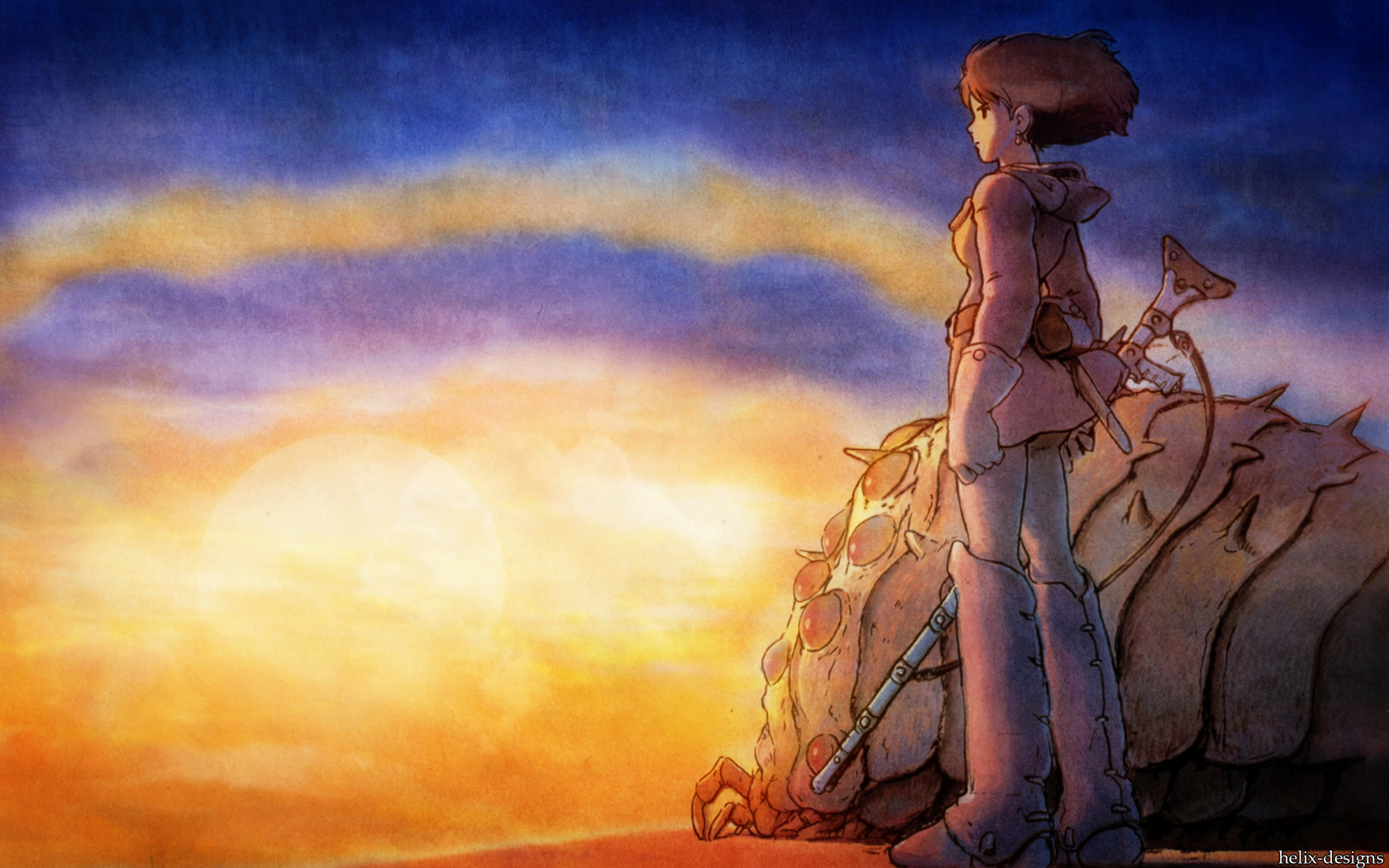

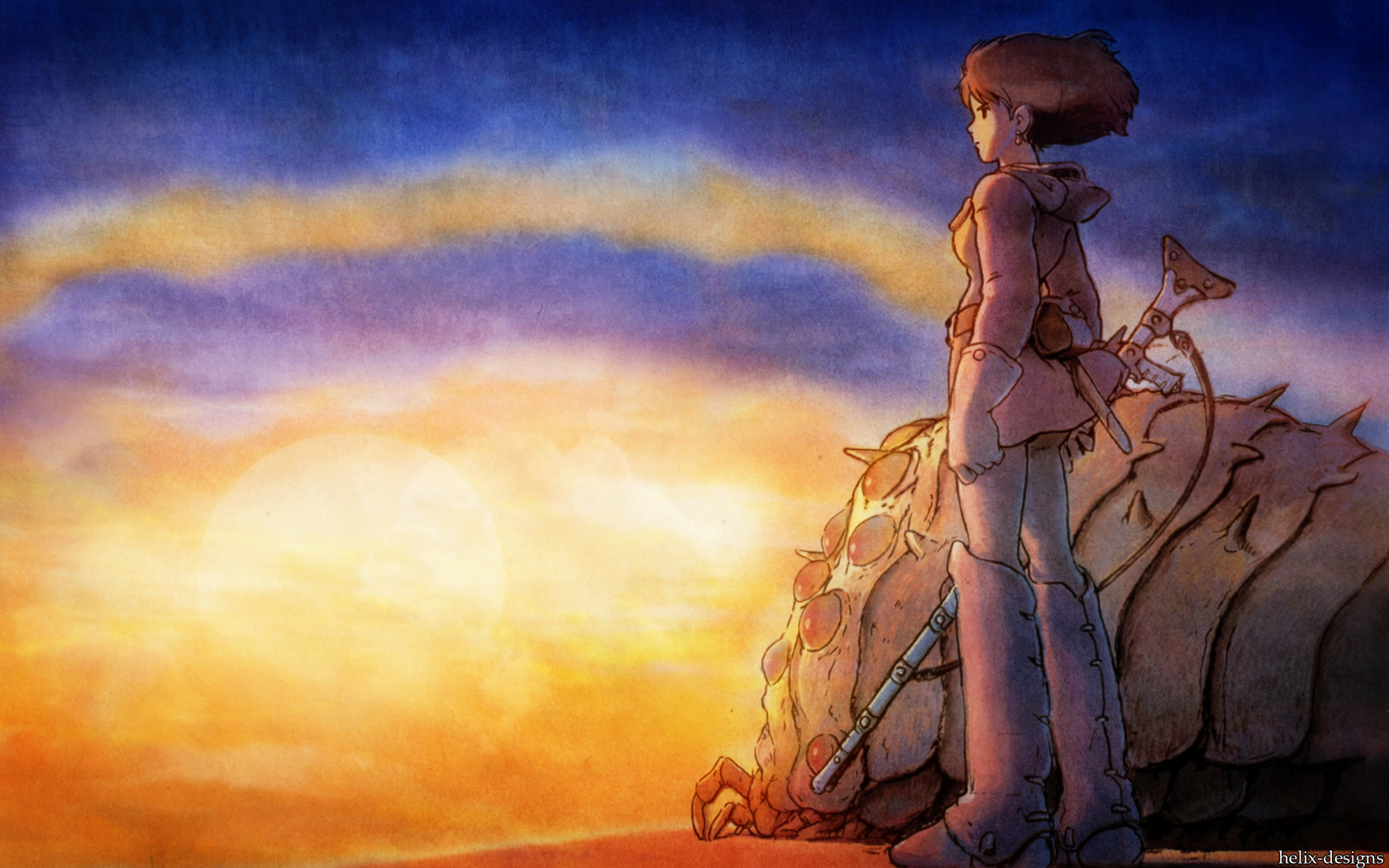

[First posted on 11 April 2014.] The first Studio Ghibli film I saw was Isao Takahata’s

Grave of the Fireflies, and I’ve been hooked to the wonderful films of this Japanese animation studio ever since. Here is a rundown of what I have seen, and what I have yet to see...

[✓]

Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind (1984), directed by Hayao Miyazaki

[✓]

Castle in the Sky (1986), directed by Hayao Miyazaki

[✓]

Grave of the Fireflies (1988), directed by Isao Takahata

[✓]

My Neighbor Totoro (1988), directed by Hayao Miyazaki

[✓]

Kiki’s Delivery Service (1989), directed by Hayao Miyazaki

[✓]

Only Yesterday (1991), directed by Isao Takahata

[✓]

Porco Rosso (1992), directed by Hayao Miyazaki

[✓]

Ocean Waves (1993), directed by Tomomi Mochizuki

[✓]

Pom Poko (1994), directed by Isao Takahata

[✓]

Whisper of the Heart (1995), directed by Yoshifumi Kondō

[✓]

Princess Mononoke (1997), directed by Hayao Miyazaki

[✓]

My Neighbors the Yamadas (1999), directed by Isao Takahata

[✓]

Spirited Away (2001), directed by Hayao Miyazaki

[✓]

The Cat Returns (2002), directed by Hiroyuki Morita

[✓]

Howl’s Moving Castle (2004), directed by Hayao Miyazaki

[✓]

Tales From Earthsea (2006), directed by Gorō Miyazaki

[✓]

Ponyo (2008), directed by Hayao Miyazaki

[✓]

Arriety (2010), directed by Hiromasa Yonebayashi

[✓]

From Up on Poppy Hill (2011), directed by Gorō Miyazaki

[✓]

The Wind Rises (2013), directed by Hayao Miyazaki

[✓]

The Tale of Princess Kaguya (2013), directed by Isao Takahata

[✓]

When Marnie Was There (2014), directed by Hiromasa Yonebayashi

Labels: cartoons, film, life

[0] This is Where You Bite the Sandwich

Friday, April 10, 2015

3:17 AM |

"Now is the Envy of the Dead"

3:17 AM |

"Now is the Envy of the Dead"

Don Hertzfeldt's latest animated effort,

World of Tomorrow (2015), is a surprising curiosity: a short but thematically rambunctious meditation on life, the future and the possibilities of being human, and the imperative of living the best life you can

right now.

Catch it however you can.Labels: cartoons, film, life, philosophy

[0] This is Where You Bite the Sandwich

Thursday, April 09, 2015

12:36 AM |

Hit Me With Your Best Shot: Nicholas Ray's Johnny Guitar (1954)

12:36 AM |

Hit Me With Your Best Shot: Nicholas Ray's Johnny Guitar (1954)

Nicholas Ray's

Johnny Guitar (1956) demands to be seen at least three times. First, it must be seen to sample it as the great film it is reputed to be: how it is a favourite among auteurs of the French New Wave, or how the late

Roger Ebert selected it as one of cinema's unlikeliest triumphs, calling it a cheap Western but also "one of the boldest and most stylized films of its time, quirky, political, twisted." And it does grow on you, hinting of some urgent and subversive message even as it hurtles on with its oversized and silly melodrama -- but one that you suspect is contained within superlative directorial vision. Everything in this movie seem contrived or preposterous when taken in as individual details -- but composed together, they make sense. Consider, for example, Joan Crawford's Vienna as she waits for the lynch mob to come and claim her. She greets their murderous rage in a magnificent white gown, the skirt of which overflows from her like a mockery of virginity,

and the she inexplicably plays the piano in a virtuoustic key that makes absolutely no sense.

Except that it does.

Second, it must be seen for the triumph of verbosity in a screenplay that it is, written with obvious glee by the blacklisted Ben Maddow. Consider this scene where Vienna confronts Johnny Guitar -- the new name that the legendary gunslinger Johnny Logan has taken on. (Here he is played by Sterling Hayden with a laid-backness that knew he may be the titular character, but that the story does not revolve around him at all.) They were lovers once and are now estranged, and during this midnight confrontation, they bring back the past with all its ghosts, a whole bundle of hurts and heartaches and betrayals.

She finds him at the bar, forlorn and drinking rum.

Vienna:

Vienna: Having

fun, Mr. Logan?

Johnny: I couldn’t sleep.

Vienna: That stuff help any?

Johnny: Makes the night go faster.

(Pause.) What’s keeping you awake?

Vienna: Dreams.

(Pause.) Bad dreams.

Johnny: Yeah, I get them sometimes, too.

(After a beat.) Here, this will chase them away.

Vienna: I tried that. Didn’t seem to help me any.

(After a beat.)

Johnny: How many men have

you forgotten?

Vienna: As many women as

you’ve remembered.

Johnny: (Imploring.) Don’t go away.

Vienna: (Reticent.) I haven’t moved.

Johnny: Tell me something nice.

Vienna: (Sarcastic.) Sure. What do you want to hear?

Johnny: Lie to me.

(After a beat.) Tell me all these years, you’ve waited.

Tell me.

Vienna: (Through gritted teeth.) All these years, I’ve waited.

Johnny: Tell me you’d have died if I hadn’t come back.

Vienna: (Sarcastic.) I would have died if you hadn’t come back.

Johnny: Tell me you still love me like I love you.

Vienna: (Sarcastic.) I still love you like you still love me.

Johnny: Thanks.

Thanks a lot.

Vienna: (Grabs the shot of rum from his hand and throws it crashing on the floor.)

Vienna: (Grabs the shot of rum from his hand and throws it crashing on the floor.) Stop feeling so sorry for yourself. You think you had it rough? I didn’t find this place. I had to build it. How do you think I was able to do that?

Johnny: I don’t want to know.

Vienna: But I

want you to know.

(After a beat.) For every board, plank, and beam in this place…

Johnny: I heard

enough!

Vienna: No,

you’re going to listen.

Johnny: I told you, I don’t want to know any more.

Vienna: You can’t shut me up, Johnny. Not anymore.

(Pause.) Once, I would have crawled at your feet to be near you.

(Pause.) I searched for you in every man I met.

Johnny: Look, Vienna. You just said you had a bad dream. We both had, but it’s all over.

Vienna: Not for me.

Johnny: It’s just like it was five years ago. Nothing’s happened in between.

Vienna: Oh, I wish…

Johnny: Not a thing! You’ve got nothing to tell me because it’s not real. Only you and me, that’s real. We’re having a drink at the bar in the Aurora Hotel. The band is playing because we’re getting married, and after the wedding, we’re getting out of this hotel and we’re going away. So laugh, Vienna, and be happy. It’s your wedding day.

Vienna: (Looks at him wistfully. They hug.) I have waited for you, Johnny.

Vienna: (After a beat.) Oh, what took you

so long?

Consider that glorious verbiage, and it is thus not to surprising to learn that Francois Truffaut once called the film a "fake Western," but means it as a compliment. Indeed, it wears its purported genre as perfect artifice, perhaps knowing full well it has more in common with the Technocolor melodrama of a Ross Hunter production, and none of the restrained machismo of a John Wayne title. (Thank God for that.) Certainly like the Hunter films, particularly those shaped by the subversive vision of Douglas Sirk, the psychosexual secrets that lurk beneath the surface become the ultimate reason to watch this film for the third time, to unbundle its hidden meanings.

I first heard about this film when it was mentioned in

The Celluloid Closet, Jeffrey Friedman and Rob Epstein's superb 1995 documentary about gay and lesbian iconography in Hollywood films. That documentary positioned the manly drag that Joan Crawford and Mercedes McCambridge take on for the film as emblematic of the sapphic subterfuge it revels in. The relationships the film clearly represents are of the heterosexual sort, but the margins of meaning seem to suggest otherwise, and the cowboy outfits the two women sport throughout is suggestive of that. When you finally consider the particular conflict that propels the story, it is actually the festering hatred the two women share for each other that makes us pause. It

is the very tension that grips the story, and the thing that holds it together: Mercedes McCambridge's Emma Small hates Vienna over the fact that the man she secretly yearns for is in love with this saloon owner -- and so, using all sorts of excuses and accusations, she tries to get the whole town riled up to either drive Vienna off, or to hang her. This is Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick's queer take on the "love triangle" in perfect representation in a film: replacing the male focus of Sedgwick's theory, the love triangle in

Johnny Guitar has the two women appear to be competing for a man's affection (although not really, because Vienna only really "likes" the man, and that's that) -- a rivalry that Sedgwick posits to be actually an attraction between the two of them.

In the film, this is specifically acknowledged when the town mayor finally wisens up to what's actually going on. Ignoring Emma's exhortation for him and his men to finish Vienna off in the end, he finally says: "It's their fight. Has been all along." He leaves them to their fate.

"I'm coming, Vienna."

"I'm waiting."

And so we come to the end of the film,

to my best shot, where the two women will finally confront each other in this crotch of a hilltop, to opposite sides of this vagina-shaped hut, where their subliminal sexual tension for each other will finally get its release....

... albeit a fatal one.

This post is part of Nathaniel Rogers' Hit Me With Your Best Shot series over at The Film Experience blog.Labels: film, queer

[0] This is Where You Bite the Sandwich

GO TO OLDER POSTS

GO TO NEWER POSTS

9:02 PM |

And Here I Am...

9:02 PM |

And Here I Am...

1:39 PM |

Headline News Blooper

1:39 PM |

Headline News Blooper

1:19 PM |

Hit Me With Your Best Shot: Jane Campion's Bright Star (2009)

1:19 PM |

Hit Me With Your Best Shot: Jane Campion's Bright Star (2009)

5:20 PM |

Gracefully, Melodramatically

5:20 PM |

Gracefully, Melodramatically

7:41 PM |

Gladys Glover and the Celebrity of Being Kim Kardashian

7:41 PM |

Gladys Glover and the Celebrity of Being Kim Kardashian

10:23 PM |

Not Mine Anymore

10:23 PM |

Not Mine Anymore

1:42 AM |

Hit Me With Your Best Shot: Colin Higgins' 9 to 5 (1980)

1:42 AM |

Hit Me With Your Best Shot: Colin Higgins' 9 to 5 (1980)

12:16 AM |

"You Will Grow to Love Me Less and Less..."

12:16 AM |

"You Will Grow to Love Me Less and Less..."

9:06 PM |

How to Write the Big Issue

9:06 PM |

How to Write the Big Issue

1:58 PM |

Pentimento

1:58 PM |

Pentimento

1:48 AM |

Alone is Not Lonely

1:48 AM |

Alone is Not Lonely

8:21 PM |

Hit Me With Your Best Shot: Martin Scorsese's Taxi Driver (1976)

8:21 PM |

Hit Me With Your Best Shot: Martin Scorsese's Taxi Driver (1976)

10:00 AM |

A Studio Ghibli's Completist List

10:00 AM |

A Studio Ghibli's Completist List

3:17 AM |

"Now is the Envy of the Dead"

3:17 AM |

"Now is the Envy of the Dead"

12:36 AM |

Hit Me With Your Best Shot: Nicholas Ray's Johnny Guitar (1954)

12:36 AM |

Hit Me With Your Best Shot: Nicholas Ray's Johnny Guitar (1954)