Sunday, October 31, 2010

8:30 AM |

Excerpt from "The Kitchen Goddess of Dogpatch"

8:30 AM |

Excerpt from "The Kitchen Goddess of Dogpatch"

[a short story in progress]

For Wilfredo Pascual It took Michael Concepcion a few days of vacillation before he decided to break the news to his mother that he was moving from his two-bedroom apartment in The Mission to a spacious loft, for half the price, in Dogpatch.

The reason, he told her in codes she could understand, was a perfect combination of savvy real estate and careful consideration for space for his growing reputation as an artist coming to terms with the wonderful fact of commissions fast coming his way. Real estate. Reputation. Commissions. The magic words. He watched her face brighten, and knew he was almost there.

“I need the big space for my paintings, Ma,” he said, “and I certainly cannot afford even an idea of that in the tiny hellholes that are the only available options in all of San Francisco.”

He calculated the weight of those words as well. The dramatic flair was something she could respond to—it was a genetic predisposition they both shared, the theatricality of things, a common arsenal of weapons they used to battle each other with. Still, he did not mention, with much carefulness, anything about moving in with Dan.

The voice at the other end of the line went silent for a pregnant span of five seconds, and Michael thought of his mother in the sunny, high-ceilinged living room in Inner Sunset she spent most of her afternoons in, after long lunches with

kumares from back home, reading romance novels, or watching with disturbing avidity the shenanigans of noontime game shows in The Filipino Channel, or fretting about the fact that he never called on her anymore. Him, and his brother Carmelo who was in Nebraska.

“Is that the area near Sunnydale?” his mother finally asked in that teeny voice, which Michael recognized as the tone she reserved for both nervousness and astonishment. He knew how to tiptoe around that tone. It contained landmines.

“Yes, Ma, but not quite,” he said. “It’s just a little farther down Arleta. Not quite Sunnydale, but close.”

“Oh, good. But there’s nothing except old, dirty warehouses there,” she said, when in fact she meant this: “What would our relatives say?” He was dismayed to know that parts of him understood the skewed snobbishness of what she was probably imagining. She had been born in privilege, a sugar princess sprung from the old

haciendas of Negros Island back in the Philippines—and life in America would become a mere continuation, if subtly reduced, of that privilege. When her late husband thought of migrating to America in 1965, she was thirty years old and demanded only two things: the place was going to be San Francisco, not New York or Boston or “barbaric Los Angeles where there are too many Filipinos,” and she was going to live in a Victorian house. That they were able to get one in the Avenues at a steal was a matter of sheer luck—something which never registered to her at all. It was par for the course of her charmed life.

The relatives, of course, especially those who would know the significations of the various neighborhoods of San Francisco—you lived for Pacific Heights, you avoided the Tenderloin—would probably not be able to grasp the idea of living in the wasteland of Dogpatch, an industrial part of San Francisco that was home to abandoned shipyards, rotting factories, and a towering sewage plant that was the landmark gracing Islais Creek. And for the most part, it was too easy to understand the discomfort: the landscape that existed after the AT&T Park in South Beach seemed alienating, all of it consisting of wide expanses of parking lots, streets lined with shuttered shops, and stretches of brick warehouses that have seen better days and have long since been abandoned. There were stories of horrible muggings, always involving poor Asian men.

What Michael could not explain to her was the gentrification the whole stretch seemed to be undergoing, that under all that rough exterior and old reputation, a growing community of artists—many of them his friends—had rooted in, started to call the place home. He fell in love at first sight with Building No. 8 off Wright Street, a former textile warehouse which still sported the roughness of the neglectful years—the grimy greenish wood, the signs over the metallic doors that read “Warning: Hazardous Materials Inside,” the dilapidated feel of the place. Not far off, in the next yard, there were piles of old cars crumpled on top of each other, a crane nearby.

“The place is fine,” he said, his reassurance measured. “The warehouses are now being converted to lofts—they are spacious and they look great. I took Danny once to the loft I’m thinking of renting. He seemed jealous, told me he wished he could live in one himself.” Danny was his cousin, and this was all a lie.

“Oh. Well, he can’t,” she said. “He’s already married, and he has that house near Tiburon. Why would a married man want to live in a loft?”

“I’ll invite you over for a visit one of these days, when I’ve settled down,” Michael said. And then: “Maybe you can even make dinner, break in the new kitchen?”

That was the final piece for a winning battle, the invitation for a feast she could make. Michael could imagine her now, at the other end of the line, tamping down a growing excitement.

I bet she is already planning a menu in her head, he thought. This was proving much too easy.

His mother demurred, of course. This was part of the game, the last act. “Are you sure, dear?” she asked, her voice becoming teenier than usual.

“I’m sure, Ma,” Michael said.

“Dogpatch,” she finally said. “I kinda like that name. I like dogs. Do you have dogs now?”

[to be continued...]

Labels: fiction, writing

[0] This is Where You Bite the Sandwich

Wednesday, October 27, 2010

3:46 PM |

Silence, Stillness, and Connection in a Crumbling World

3:46 PM |

Silence, Stillness, and Connection in a Crumbling World

Tsai Ming-liang's

I Don't Want to Sleep Alone [2006] is my introduction to the Malaysian director's oeuvre, and I am deeply shamed. Where have I been cinema-wise the past few years? In college, I used to know the latest currents of world cinema so well, and now I only have this wasteland of unawareness, and I hate playing catch-up. Thank God then for this time in Iowa. In any case, I was startled by the audacity of this film, which carries the poetic sensibility of Yasujirō Ozu and the found story aesthetics of Armando Lao. This is a silent film that masquerades as a movie with sound -- and so one must learn to appreciate it in the way its images unfold, which is not hard to do since the cinematography is breathtaking, even if the landscape it depicts is that of the underbelly of Kuala Lumpur. Lao's protegee Brillante Mendoza has done similar work in

Serbis [2008] -- e.g., the long-takes, the brilliant use of ambient noise, and the quietly observant camera that takes in the poetry of decrepitude -- which in fact has a cousin in Tsai's

Goodbye, Dragon Inn [2003], both of which tell the stories of crumbling cinemas as a reflection of the riptide of turbulence in Asian society. The only difference between Mendoza and Tsai is the latter's preference for silence and stillness.

Silence and stillness. Those are good words to describe

I Don't Want to Be Alone, which signals Tsai's return to filmmaking in Malaysia after a career that has mostly burgeoned in Taiwan. I came to this title thinking that it would give me an idea of how another Asian nation, this time Malaysia, would tackle a gay story. (I am undertaking an unofficial research of Asian pink cinema, I have no idea why.) But I don't think I can label this gay at all, although the filmmaker is certainly openly gay. Yes, there is tenderness in the way the Bangladeshi undocumented worker cares for the mauled Chinese man, but there is no overt sexuality here. In fact, the most overt sexual situation occurs between the Chinese man and the lady boss and later, the waitress who works for her. Near the end, there is also the brief gesture of tenderness between the two men -- but I don't know what to make of that. I can say though that, in the film, there is only a limning of that universal search for connection in a brutal world. And what to make of that enigmatic end? I have no idea, but it reminds me of the puzzles in the last shots in Stanley Kubrick's

2001: A Space Odyssey [1968] and Michael Haneke's

Cache [2005]. I guess the images are there for us to ponder and ponder some more, and so I shall do just that.

Labels: directors, film, queer

[0] This is Where You Bite the Sandwich

10:54 AM |

The Things We Do Here

10:54 AM |

The Things We Do Here

As I write this, it is a late Tuesday in the waning days of October, and I am hating the chatter of this couple on a study date in this crowded café. They are in the next table behind me, and try as I might, I become an unwilling eavesdropper into their conversation—something the music piped right into my ears with my earphones cannot even remedy. Sigur Ros, James Morrison, the Hans Zimmer soundtrack from

Inception are powerless. The girl is Asian and seems inappropriately giggly; the guy is blonde and strikes a macho pose in his probing questions and corny jokes. The guy says something bland or inane, and the girl giggles and provides chatty fodder for their conversation’s twists and turns, including strange detours into the Oedipus Complex and living in Canada. They have gone on with this getting-to-know-you game for a while now, and I am on my second cup of café latte. I am hungry and loaded with caffeine, and I cannot write the story I have sworn to finish today, or else. I can feel a headache coming. It is 7.27 in the evening in The Java House along East Washington Street, a football pigskin’s throw from the pedestrian mall in the center of town. I think about the grocery I have to buy in Bread Garden Market after I finish this cup of coffee. The café’s wifi is down, and I miss the occasional Facebook breaks I take from my writing, where the “occasional” is considerably longer than the actual work at hand. The couple behind me now talks about the “rules” of friending people in Facebook, and I roll my eyes. I think hazily about procrastination, and decide to do something about this habit later. I think about missing gym for four days now. I think about the stories and articles I have yet to finish. I think about the books I have to read, and the films I have to screen. I think about my remaining days in America. I think about time slipping fast.

I think about time a lot these days.

I think about the past weekend in Chicago, and think about how I had spent Monday in a pursuit of cocooning rest. This meant movies and books and general avoidance of the outside world. Outside, Iowa City is getting cold. The cold snap of autumn has gone towards its most extreme. The TV news tells me there is a storm brewing all over the Midwest. There are tornado warnings for Mississippi and Wisconsin. I find myself dressing in a flannel shirt and a sweatshirt and a coat and a pair of canvas skate shoes. I look at myself in the mirror and think about how, with such a simple sartorial act, I have gone suddenly "native."

This is not a usual day for me here in Iowa City. Often, each day is sunny and free of irritating moments—when it does become chilly, the beauty of trees turning gold in the fall offsets it. This is why I am recounting all this in detail, because it is unusual. My stay here has been beautiful, and all that is coming to an end soon, in a few weeks. I think about time a lot these days. And how it slips away so fast.

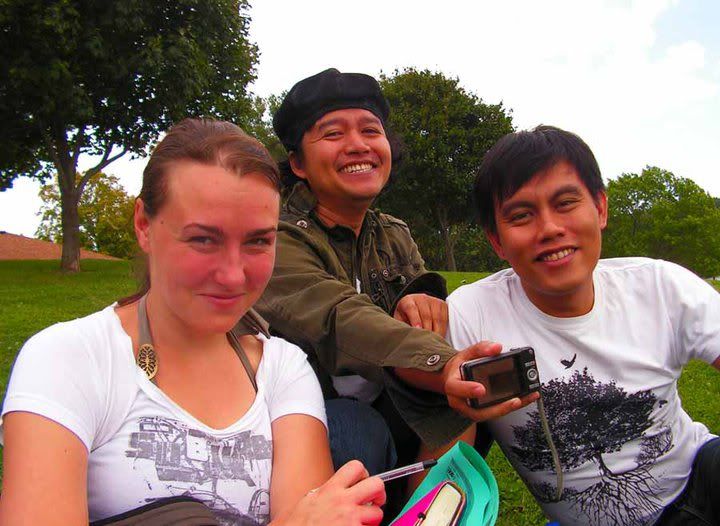

Here’s what a normal day here is for me. There’s waking up late in the morning, then gym at the nearby Fitness First, then lunch at A Taste of China along Linn Street (or some other place when rice does not do it for you anymore), then coffee-aided writing at The Java House or T-Spoon, then the library till midnight, then home. On weekends, there’s music at The Mill or beer at Fox Head or Donnelly’s. The bibliophiles among us, who are most of us, go to Prairie Lights or The Haunted Bookstore or Murphy-Brookfield for a relief of their book addiction. We are kept busy some days attending to lectures and readings and film screenings and parties and excursions, most of which are optional. We are told that our primary duty in this writing residency is to write. And so we do. I sleep late at night to catch up on work and reading, aided for the most part by Red Bull in cans, something that is treated almost like water here. I have learned to hate the television a month before; the remote control is hidden behind the set, in an attempt to make turning the TV on a little harder, a mile shy of temptation.

In the rooms around mine in The Iowa House Hotel where we are billeted, the writers are battling with words and turns of phrases—and so must I. It is the best kind of writerly pressure. Compatriot Edgar Calabia Samar is finishing the introduction to his dissertation, an anti-detective novel in Filipino. Hong Kong’s Lai Chu Hon is finished with her novella about girls jumping off buildings, and Russia’s Alan Cherchesov is finished with his novel as well. Indonesia’s bestselling author Andrea Hirata began his fifth novel in the beginning of the residency, and is now finished with it. Singapore’s Thiam Chin O has finished four chapters of his first novel about two couples in an unnamed Asian island after the tsunami. Egypt’s Ghada Abdel Aal is biding her time, having decided not to write at all (except her columns back home!), occupied as she is with pressing interviews and readings and classroom visits. She has so far appeared in The Washington

Post, which has done a feature on her as the author of a widely popular television show back in Cairo based on her book

I Want to Get Married! She tells me that as a Muslim woman, “sometimes I am treated here more as a symbol than as a person.” Argentina’s lovely (and

uncomplicated! she would love that word) Pola Oloixarac, one of Granta’s choices for best young Spanish novelists, makes the conference circuit in Spanish language literature from Boston to Barcelona. India’s Chandrahas Choudhury gives readings of his first novel everywhere. Others are finishing screenplays and poetry collections. We—all 38 of us from far-flung places in the world—are all busy writing, when we are not partying or doing readings or visiting places or meeting authors like James Tate, Samantha Chang, Marilynne Robinson, Mona Simpson, Bo Caldwell, Yiyun Li, Jane Smiley, Xu Xi, among others. We get to travel, too, to get the breadth of America, which is part of the pursuits of this program. So far, there has been San Francisco for me (and Cody in Wyoming, Portland, and New Orleans for the others), as well as Chicago, and soon Washington, D.C. and New York. In those places, the touristy stuff prevail: in Chicago, there’re the architectural boat tour, the art overload in the Institute of Art, the plays in the theater district, the dancing in Boystown, the restaurant-hopping in Wicker Park, the skyline from Museum Campus, the view of the world from atop Willis Tower, the shopping along Michigan Avenue, among others; in San Francisco, there’re Alcatraz and Fisherman’s Wharf and the Golden Gate Bridge, the winding descent of Lombard Street, the bohemian air of Haight-Ashbury and The Mission, the nightlife in the Castro and Valencia Drive; in Washington, D.C. and New York, there will be more of the same. The goal is immersion in the culture, as well as to write. I came here to write my second novel, but somehow ended up writing short stories instead. I am almost halfway finished with that new collection

Where You Are is Not Here, all set in places not in the Philippines. When IWP writers greet each other in the morning, our hellos are often followed by this phrase: “How’s your word count?”

You can say that Iowa City is a writer’s dream. When Teng Mangansakan III, who was a fellow two years ago, told me earlier that this experience would be life-altering, I didn’t know if I could believe him, but now I know for sure. Remember those fantasies you keep about spending your days not preoccupied with such trifling concerns like a day job, spending only time chasing words and inspiration? The residency in the International Writing Program is the fulfillment of that fantasy—but after its expiration date comes the thought about having to go back to the ordinary world, where you have to take in again all those nagging everyday concerns, which compete with the fact of being a writer. Alas.

But nevertheless. To get a taste of this life, to be given this opportunity, that is enough.

Labels: iowa international writers program, life, travel, writers

[1] This is Where You Bite the Sandwich

7:24 AM |

My Own Private Paris

7:24 AM |

My Own Private Paris

Remember that scene in Sydney Pollack's adapation of

Sabrina [1995] where Julia Ormond as the title character has this huge corkboard in her Paris apartment which she soon fills up with notes, clippings, and pictures -- all souvenirs of a life in transformation?

I saw the film again this morning in HBO, and I was reminded that I have always loved that long sequence, although critics then snapped that in Billy Wilder's 1954 version, that transformation involving Audrey Hepburn only required a quick montage. I always thought that assessment unfair: while there's no denying the greatness of the original, the late great director Sydney Pollack was more cognizant, in my opinion, about the theme of transformation of the story. Sabrina's blossoming, which required sequences of her walking Paris alone and getting tutored in cosmopolitan sophistication by Fanny Ardant and Patrick Bruel, was a vital part of the film, which all too soon becomes a vehicle for Harrison Ford as Linus and his transformation from a cold and calculating businessman to a warm and receptive lover.

But what struck me the most was this: if I were my own Sabrina, Tumblr is my corkboard, and the Midwest is my Paris. Yes, my version is a little scaled-down and maybe less glamorous than the Hollywood version, but damn I could see the parallels.

Labels: film, life

[0] This is Where You Bite the Sandwich

Tuesday, October 26, 2010

9:15 AM |

Strings Attached

9:15 AM |

Strings Attached

Mehdi Ben Attia’s

Le Fil [

The String, 2010] is not a great film, but it is good and is endlessly fascinating — which was a total surprise, since I have been swamped most of my life with gay films that are carbon copies of the same themes of prosecution or coming out or the delicate intricacies of gay friendships in weekend getaways. This one is different, in the way the French seems to be able to achieve difference: in that particular tone French filmmaking achieves, something that delicately balances immersion and distance as we observe realistic and peculiarly fleshed out characters as they go about their daily lives, coping with the everyday bumps the narrative gives them. This is a beautifully photographed, elegantly-paced French-Tunisian film about a wealthy architect from Paris who goes home to Tunisia after his father’s death, where he must confront his homosexuality in the context of his society’s class-consciousness and Islamic mores. Then there are also the expectations of his mother (the glorious Claudia Cardinale) who pressures him to marry. These are the metaphorical strings of the title. Everything comes to a head when he finds himself falling for a young artist, a sometime handyman who lives with them in exchange for free rent. This is the type of queer filmmaking I’ve always wanted to see from Filipino directors — a glossy, sexy, but also socially engaging (but non-pedantic) portrayal of the middle class and homosexuality, without the poverty porn and macho dancing aesthetics that plague so much of Filipino gay cinema. For the most part, this has been achieved with middling success only in Joselito Altarejos’

Little Boy, Big Boy (an interesting film that failed because of poor casting) and Adolfo Alix Jr.’s

Muli and

Daybreak (both of which are a little too earnest in their melodrama).

Labels: film, queer

[0] This is Where You Bite the Sandwich

9:11 AM |

No Chimes Here

9:11 AM |

No Chimes Here

The problem with Wing Kit Hung’s

Soundless Wind Chime [2009] is that it wants to be poetic and engaging, but refuses to commit itself to the emotional core that would have brought those qualities on. It is an attempt to ponder on the themes of death and memory, love and loss — but mistakes long shots of people endlessly looking sad [or sleeping] for profundity. Which is a shame, because the story — about a young Chinese food delivery boy in Hong Kong and his Swiss lover — has a potential for an explosive exploration on interracial romance. But that is not even the biggest problem with this film, which was nominated for the Teddy Award in the Berlinale. Hung’s use of intercutting time frames as well as merging of reality and memory are audacious and applaudable — but he never for once makes us believe in the bond between the lovers. They share passionate embraces and they move well together, but there is not a single spark of intimacy between them. And so, when we are finally asked to consider their tragedy in the end with the fullspring of pathos, it just does not come, and we are forced to end the film having realized we have wasted too much time rooting for people who does not care about being rooted for in the first place.

Labels: film, queer

[0] This is Where You Bite the Sandwich

Monday, October 25, 2010

12:24 PM |

Two Views, One Roscoe's

12:24 PM |

Two Views, One Roscoe's

Here’s a funny thing in a note of perspective. In Chicago, one of my fellow writers in the International Writing Program referred to

Roscoe’s in Boystown as a “sleazy” dance bar with too much sexual tension. I couldn’t help but laugh inside and think: “That’s sleazy? You should see Why Not Disco in Dumaguete.” Because compared to that sleaze hall, Roscoe’s is a wholesome daycare center.

[photo by andrew collins from about.com]

Labels: friends, iowa international writers program, life, night life, queer, travel

[0] This is Where You Bite the Sandwich

Thursday, October 21, 2010

2:02 PM |

In Leo's Room

2:02 PM |

In Leo's Room

You know how it is. There's nothing much to do as evening deepens. So you go to and through a torrent site, and download at random some title that seems a little interesting. But you don't expect anything. The previous two movies you've downloaded before this one went straight to the trash bin after a few minutes of inept filmmaking in gross display.

So you didn't think Enrique Buchichio's

El Cuarto de Leo (Leo's Room) [2009], a Uruguayan film, would be any different. Maybe a smidgen better, but that's it. But there you are, finding yourself wallowing in the glorious byt understated gravity of everybody's performance, especially that of Martín Rodríguez as the titular character who lends the film just the right amount of bravado and vulnerability. It's all in his face, the way his eyes winces and brightens, and the way he bites his lips. The way his character navigates loss and being lost is rendered so well, you begin to see your own story right there on the screen. Leo's pain, and that of Caro's, becomes universal. There are no hysterics here, no go-for-broke melodrama -- but it had you crying buckets. You come to the end, and you know you have just seen a great film.

Labels: film, queer

[0] This is Where You Bite the Sandwich

Monday, October 18, 2010

7:10 AM |

Murdering the Humanities

7:10 AM |

Murdering the Humanities

My friend, the much-missed speculative fictionist Baryon Tensor Posadas, recently posted a link to this New York

Times column by the cultural critic Stanley Fish, where Fish essentially announces the death of the humanities, especially in the academe. I paid close attention because this was personal: I am a teacher in the humanities, and I write, and the production and cultivation of culture has always been the focal point of my existence. I paid close attention because if the humanities is dead, has my life so far been essentially worthless?

In his column, Mr. Fish takes to task George M. Philip, the president of SUNY Albany, who last October 1 "announced that the French, Italian, classics, Russian and theater programs were getting the axe." He then does an extensive postmortem about how Mr. Philip got away with murder, and goes on to entertain the age-old debate once more about the worth of the humanities in contemporary life, especially in a world racked by a recession. He writes: "What can you say to the tax-payer who asks, 'What good does a program in Byzantine art do me?' Nothing."

He goes on:

But keeping something you value alive by artificial, and even coercive, means (and distribution requirements are a form of coercion) is better than allowing them to die, if only because you may now die (get fired) with them, a fate that some visionary faculty members may now be suffering. I have always had trouble believing in the high-minded case for a core curriculum — that it preserves and transmits the best that has been thought and said — but I believe fully in the core curriculum as a device of employment for me and my fellow humanists. But the point seems to be moot. It’s too late to turn back the clock.

What, then, can be done? Well, it won’t do to invoke the pieties ... — the humanities enhance our culture; the humanities make our society better — because those pieties have a 19th century air about them and are not even believed in by some who rehearse them.

And it won’t do to argue that the humanities contribute to economic health of the state — by producing more well-rounded workers or attracting corporations or delivering some other attenuated benefit — because nobody really buys that argument, not even the university administrators who make it.

There are no easy answers to the dilemma, and Mr. Fish does not even offer anything. Might as well. But he does underscore the notions of politics and ineptitude in the part of leaders who should know better as really the main causes of humanities' death. Academic leaders, he says, are supposed to be cheerleaders of the pursuit of education and knowledge, not undertakers who are only concerned about the bottomline. I firmly believe that something fundamental dies when the humanities in our culture is allowed to die. It is like a skewering of our soul.

I am already living through this. In the university where I teach, for example, I was shocked last semester to find out that the biggest college we have has dropped literature from its curriculum, simply because its autonomy from CHED declared it could. In essence, they rendered Philippine and world literatures unnecessary in the making of a thinking professional. It was a sad day when I found out this. And I could not just fathom that notion: how do you go to college without at least having a smidgen of literature in your academic life? What are we trying to produce, unthinking and unlettered robots? It felt like a kind of death.

My fellow teacher Sherro Lee Lagrimas also wonders: “What will they remove next? Have they forgotten this C.S. Lewis quote? ‘Literature adds to reality, it does not simply describe it. It enriches the necessary competencies that daily life requires and provides; and in this respect, it irrigates the deserts that our lives have already become.’” I’m not sure they have forgotten; they just probably do not care anymore.

All these also make me realize that sometimes those who are in-charge of our educational institutions, good-intentioned they may be by the cuts that they make, are often blind to the big picture. A friend, the Hong Kong-based journalist Heda Bayron, once told me a story: “A couple of years ago, I had the pleasure to meet and share a dorm room with an MIT professor emeritus in French Studies. She teaches French literature and fills a lacuna in the education of MIT’s math and science geeks, making them much more well-rounded human beings.

Learning French literature or Chinese literature also makes MIT students more competitive in the global stage because success is no longer about your math aptitude or quaint skills, it’s also about how you conduct yourself. And you can only rise above the crowd if you possess a wider perspective.”

I don't know why but this whole thing made me think, somehow, of the writer Ayn Rand, but in a different light. In her polemic novel

Atlas Shrugged, conversant of her belief that capitalism is the very engine of the world, she paints a possible time when all of the world's business leaders, innovators, and entrepreneurs go on a strike, hide from the rest of society who does not care for them, and watch that society slowly eat itself up from its uselessness. I wondered if somebody could write an artist's equivalent of

Atlas Shrugged, where, instead of business powermen going on strike, artists will leave the rest of the world behind to wallow in its filth of no artistry and no soul.

My question though is this: if we follow these people's logic about the humanities not "contributing" anything to the economy or whatever, I counter with this idea of bankers and Wall Street people having seriously fucked up the economy and have given "the American way of life" the black eye. Why aren't business schools being closed down?

And then this: when I was in San Francisco, the city was trying to gentrify the down-on-its-luck Dogpatch industrial neighborhood near Arleta by inviting artists to come in and enjoy the low-rent warehouses. And many artists have come in, turning many of these unused warehouses into studios. There is now an upswing in the standard of living in that community, still in the beginning stages, but it's there. The city of course knows that this effort to bring in artists would soon bring in other people and other businesses -- cafes, boutiques, galleries -- and soon bring in the dollars. This has happened in New York, in Chicago, and in many other cities.

And soon, of course, this is what happens: the artists who have gentrified the neighborhoods in the first place have to move out because they can no longer pay the rent.

Gah.

In both cases, artists always seem to get the short end of the deal.

On another note about Stanley Fish, he posits that Rob Epstein and Jeffrey Friedman's

Howl (2010), the pseudo-biopic of the poet Allen Ginsberg (played here by the swoon-worthy James Franco) is the first film to be

a perfect demonstration of literary criticism at work. I cannot wait to see this film in New York.

Labels: art and culture, economics, issues, rants

[6] This is Where You Bite the Sandwich

5:06 AM |

At Home in the Beginning of Things

5:06 AM |

At Home in the Beginning of Things

I was just reading this New York

Times article on David Remnick, the editor of the

New Yorker, and I found myself entertaining the weirdest notion: what if when I go to New York this November, I'll march right up to Condé Nast in 4 Times Square and hand in my resume? Getting a job there would be a long shot by any means, but it is the kind of adventurous "why not?" candor that has somehow defined who I am the past few months. America, I think, has changed me.

As a writer-in-residence for the University of Iowa's International Writing Program, I have come to love how this whole trip has essentially been a period of endless discovery and creativity. I cannot be thankful enough.

Every thing about America tells me I belong here. Of course, friends who have been here (Al, Krevo, Karl, Moses, etc.), or who are from here (Danny, etc.), have always been telling me this my whole life, once they get a firm grasp of my sensibility, my personality, and what I can do. "You're wasting yourself in a small town," they keep telling me. I didn't really believe them. I was idealistic then, more than 15 years ago, about staying where I had been my whole life, willing to buck the trend of people I know leaving home all of the time to seek their fortunes elsewhere. I had told myself,

I can be a success even in the smallness of Dumaguete. And I think in many ways that belief has proven prophetic. But I have become racked with so much doubt lately: the wages of sometimes staying in a small town is having to deal with small people. They know who they are, and battling with them seems so pointless and exhausting, like teaching logic to troglodytes.

America's blessing is its expanse. It's huge, it takes so much in. In this side of the world, you can be who you really are and small people can be left behind in their small worlds where they cannot touch you. "You belong in America," those friends told me. I couldn't really believe them then. How could I? All ideas I know of America are from the movies and the television shows we consume -- not exactly objective renditions of what America really is. Experiencing it first-hand, however, has been the game-changer. I have lived in foreign countries before. Japan was lovely, but I have always been made to feel like a

gaijin there. It didn't feel like home. Here, America does. Still, I know it is not a perfect place, I know that. Sometimes I see things here that break my heart.

But here, I am most myself, and it is a place that has made me happier than I have ever been in my life. And I don't really want to go home just yet. I love Dumaguete, but ... There's that "but" I cannot define. My friend Bing emailed me yesterday: "

I know. I feel the same way. I told a friend that I should be kind of feeling excited or at least feel something positive when I went to Silliman the first time after I had been back, but I just didn't feel that way. I think these feelings are telling us something. Come back for now and plan about going back there again soon." That's how I feel, too.

Sure, I'll go back to the Philippines for a while. I'll finish things. I'll lay the foundation for projects that have to be accomplished for the sake of the future. This and that. I owe my beloved Dumaguete that much. But I don't think I'll stick around for long. Maybe one or two more years, I don't know.

And as for love, I think I can find it finally here.

Labels: life, travel

[8] This is Where You Bite the Sandwich

Sunday, October 17, 2010

3:58 AM |

Nostalgia is Dead

3:58 AM |

Nostalgia is Dead

[via

gang badoy]

Labels: cartoons, humor, life, memes, memories

[0] This is Where You Bite the Sandwich

Saturday, October 16, 2010

5:11 AM |

Carving Out Time and Space in the Midwest

5:11 AM |

Carving Out Time and Space in the Midwest

People have asked me a lot, “Why are you in Iowa? What are you doing there? Isn’t Iowa just one huge field of corn?” And sometimes people back home don’t even bother to listen, and attempt hello with “So how’s Ohio?”

Iowa, not Ohio. They’re two different states, I want to correct them. Most of the time, I don’t even bother. I suspect sometimes that most Filipinos find it easier to pronounce or remember Ow-hay-yow than the airy two-syllable conundrum of Ay-wah.

So yes, there’s a lot of corn here. Red barns and silos, too. The whole shebang. When I arrived here in late August, someone native made a jokey reference to the whole area—from Des Moines to Denver—as “fly-over country.” Which meant that this was Nowhere Land for most people in Continental United States, so much so that commercial airliners just “fly over” it.

But what’s in Iowa City? The Filipino writer Edilberto Tiempo asked the same bewildered question when he was sent as a Fulbright scholar in the 1930s to America, and was promptly instructed to get to this heart of the Midwest, four hours west of Chicago. In explanation, he was told something that remains true until today. In Iowa City, you have the best and most influential creative writing workshop in the world. In Iowa City, the world of literature converges to make it the hometown of writers from all over—and that if you are a writer of some note, you must make at least one pilgrimage to Iowa City. In 2008, UNESCO solidified Iowa City’s reputation as a literary capital by designating it a City of Literature, alongside Edinburgh in Scotland, Melbourne in Australia, and now Dublin in Ireland.

The University of Iowa’s Writers’ Workshop, founded in 1936, remains the finest program for creative writing there is, made world-renowned by the poet Paul Engle. (Today, its director is the writer Samantha Chang.) The Workshop has also set the template for how creative writing workshops the world over are structured and ran. In 1961, returning to the Philippines after their graduate stint in Iowa, Dr. Tiempo and his wife the National Artist for Literature Edith Lopez Tiempo set up what is now known as the Silliman University National Writers Workshop, patterned of course on the one in cornfield country. In its early years, Mr. Engle visited the workshop in Dumaguete—and then invited the Filipino fictionist Wilfrido Nolledo and the Korean poet Ko Won, both fellows at the Silliman workshop, to come back with him to Iowa City. Both writers formed the core that would soon become the International Writing Program, a residency founded in 1967 aimed at bringing international writers to the Iowa campus where they could participate in the community’s literary life and devote three months to their own writing projects. (Today, the IWP director is the poet Christopher Merrill.) I am part of that program this year, together with Ateneo poet Edgar Calabia Samar. It is a privilege that has included such Filipino writers as Susan Lara, Charlson Ong, Marjorie Evasco, Rofel Brion, Sarge Lacuesta, Teng Mangansakan, and Vicente Garcia Groyon III. The IWP’s grandest alumnus so far, among so many luminaries, is the Nobel Prize winner for literature from Turkey Orhan Pamuk.

And so, when people ask me what I am doing in Iowa, I just tell them that as a writer, I am merely going back to the mothership.

Iowa City is easy to get used to, at least for me. Not once did it make me feel homesick, and every single day since my arrival has since become an exercise in trepidation of not wanting to go “home,” because this city already feels so much like home. You see, Iowa City has the same feel as my hometown of Dumaguete City—both are university towns, both are small but sophisticated, both are culturally active in ways that compete with cities bigger than them. In Dumaguete City, we wear

porontongs and

tsinelas and white shirts like a uniform. In Iowa City, the girls wear daisy dukes and the guys wear flannel and jersey shorts.

“It is my blonde Dumaguete,” the writer Rowena Tiempo Torrevillas—who is both Dumagueteña and Iowan, and so she knows what she is talking about—once said. I agree with her.

The only thing different here is the weather. One day many weeks ago, for example, they said it was the last day of summer in Iowa City. I had supposed they were right about that—but to me they have completely different conception of sun and summer here. The slightest instance of blue and the tenderest warmth here is considered summertime. Once, on a walk across campus on a slightly cloudy, slightly chilly afternoon, I chanced upon a pasty-white college boy who had taken the liberty of taking off his shirt to lie on the grass in front of the Old Senate with its shining golden dome. He was sunbathing. I looked up and there were indeed slivers of sunshine peering from behind the clouds. I found it amusing—the way they may find it amusing that I get so cold at 15ºC. It’s a coat for me at that drop of temperature. “You only need a sweater, or a cardigan!” I can hear them thinking. But my body knows only the vocabulary of humidity—not this dry, crisp chill in the air. Not the shivers that come with the wind.

In my three weeks in the Midwest—a span of time that had been spent in an endless cycle of all sorts of acquaintance and adaptation—my body was particularly slow in its attempt to settle down with this change of climate and circadian rhythm, to the point that I had actually taken to bed, sick with both jet lag and coughing. But I took it as an ironic announcement by my biology that I was—

am—alive, that I am responding to strange, but ultimately sweet, stimuli. I knew I was flying into an adventure, and I was determined to wring out the best that I could from it before I would fly back into the familiar humidity of back home.

Still, I must admit that settling down in a new place also requires a certain kind of diligence to get out of an instant habit of cocooning. It is entirely understandable and entirely human, of course, this instinct to carve out a space of warmth and the relatively familiar amidst strangeness. A new place, after all, assaults you with volleys of newness—and the details are sharp: people talk differently here; they do things differently here; they move differently here. The smells and the sounds are new; the texture of things are different; the vistas may be familiar from the movies you have seen, but they suddenly come barging at you with the intimidating shock of proximity. This new place is suddenly your context, your present—and you have not prepared well for that change. Your only resort is to slip out, sink in to that cocoon of your making.

In my case, the cocoon was my hotel room. It is a rectangle of generic space, the type that lends itself well as a canvass for your projections of what makes for home far away from home. There is the one grand window that overlooks the Iowa River, there is the bed with its blankets and pillows and comforter, there is the writing desk, there is the tiny refrigerator that soon gets stocked up with food the texture of which brings back a sense of home, there is the bathroom, there is the closet, there is the television. I stayed in this room for days, barely venturing out.

But when I was finally ready to do battle with all these unfamiliarity, I began to sniff out for that one inviting day that was agreeable. I ventured slowly out into the unknown world that was Iowa City, and then I began to conquer it bit by bit, each step a discovery, each decision an adventure into turning the strange into the familiar.

And so it has. Prairie Lights Bookstore. Linn, Dubuque, Clinton, and all the other streets. The Mill. Bread Garden Market. The Englert. The Java House. A Taste of China. T-spoon. Studio 13. George's. They have become home, have become part of what is familiar to me. I thought this when I ventured out of my hotel room this morning, after freshening up from a good session at the Fitness East gym: you’ve finally really settled down when you don’t even notice anymore you are surrounded by blonde and blue-eyed people everywhere you go.

Labels: iowa international writers program, life, travel

[2] This is Where You Bite the Sandwich

3:35 AM |

A Jet-Lagged Person's Guide to Knowing America

3:35 AM |

A Jet-Lagged Person's Guide to Knowing America

People who have traveled extensively don’t tell you much about jet lag. “Oh, it’s just your body getting used to the new hours of the sun,” they tell you, most often in a flippant way. They make it sound like having a minor hangover that can be cured by Advil and three glasses of water.

For most of my travel life, the most extensive time difference I have had to bear consisted a total of two hours and thirty minutes—a miniscule time lapse, also largely irrelevant, because I went from east to west (from Manila to Chennai) and essentially followed the path of the sun.

When my brother Rey was home from L.A. for a few days last August, he spent his jet lag hours bothering us in our wee hours (“Let’s grab a bite to eat!” he would text me at 2 A.M.), and the rest of the day snoring out the sun.

This does not sound like an ordeal that equals misery in some level of Dante’s hell—and so, off I went, on an 18-hour journey across the Pacific, to Iowa, to an alien timezone known as Central time that soon would wreak absolute havoc on my body. Jetlag, nobody tells you, does its wrecking in increments at first, in such killing subtlety, lulling you into believing in the beginning that no jet lag was actually happening. It hit me full force on the third night. In came the awful insomnia, the splitting headaches upon waking up, the sudden bouts of disorientation, the untimely narcolepsy that plagues the day hours. “Go out,” I was soon told. “Let your body get used to the sun. Get your circadian rhythm in sync with the daylight. Resist the temptation to sleep in the afternoon!”

By the fourth day, I developed a coughing spell so fierce I had to retreat to my hotel room for three days to convalesce and wasted an entire week in an effort, with the help of a regimen of the strongest dose of Mucinex, to get better. The cough eventually went away, after a little more than two weeks—a most tiring period.

“I think I’m just developing allergies to all this clean, crisp Midwestern air,” I told a friend when I was on my last days of getting better. Which was true. I thought of my relentless coughing as essentially my lungs clearing out the humidity and the pollution of Third World air, and breathing in the alien but clean, thinner air of Iowa, filtered perhaps by the cornfields that surrounded this tiny academic city, home of the greatest creative writing workshop in the world.

“Well, it’s also the start of autumn,” one helpful Iowa native informed me. “It’s quite normal to get sick these days. Getting from summer to fall can be hell. Have you had your flu shots?” I said no, and was promptly told I could have it in one of those chain groceries; Walgreens for instance.

For two weeks, my body, used to the humid battering of the tropical air, was telling me in very dramatic psychosomatic manifestations that America was different—the air was different, the sun was different, the people were different, their sense of normal was different. But I also knew I needed this difference.

In America, I am often asked the same question: “What surprised you the most about the U.S.?” I find that question quite telling. Back home, our usual ice-breaker question for foreigners we find ourselves having small talk with is: “How do you

like the Philippines so far?” In a sense, this is reflective of some unconscious form of yearning for approval, as if we are begging the one we are interrogating to “like” the country based on experience and not newspaper headlines. The American question, on the other hand, is quite telling of everybody’s awareness here that there are many ideas of “America” in the world, many of them myths and stereotypes created by Hollywood and dreadful FoxNews. For many Filipinos, for example, it is the ultimate Mecca of travel and work, the one destination everyone back home longs to go to, judging from the long desperate lines at the Embassy along Roxas Boulevard, or the spiking enrolment to college courses that are ready-made for a Stateside existence. In fact, I told Edgar Samar, my fellow Filipino participant in the International Writing Program here in the University of Iowa, that I couldn’t help but sometimes scrutinize the look and the feel of the U.S. visa and the Social Security number we had obtained as part of the IWP—“So many people back home would die for these,” I told him.

My answer to the question, of course, is a response to my idea of America, which the writer Anthony Burgess once summed up as “consisting of five provinces: the Wild West, Southern California, Chicago, some generic university town, and New York.” Behind our generic ideas about it, there are breathing people here who may be different in looks and in other things—but they are also, surprisingly, just like me.

Also this: the overwhelming kindness of people, especially of the Midwestern kind. I found this in abundance in Iowa City, in Chicago. “Everybody’s so friendly here,” I told a newly-minted Caucasian friend, and she laughed and said: “Wait till you get to New York.”

Still, I was surprised by that friendliness, that easy “Good morning” or “Good afternoon” or “Hi, hello” that spring from everybody’s lips, from total strangers. It is not at all unusual for complete strangers to bump into each other and inquire, in such intimate tones, about the scores of an ongoing baseball or football game. On a park bench in Viagra Triangle in the middle of Chicago, I had the most interesting free-flowing conversation with a third grade teacher who was sitting beside me grading her students’ homework. We talked about snow and books, just like that. Also, while waiting for the Chicago Symphony Orchestra to perform its inaugural concert with maestro Riccardo Muti in Millennium Park, an old college friend (now a Chicago local) and I bumped into an old man, a classical music aficionado, who began telling us his passion for architecture and old chairs, just like that. These things never really happen in the Philippines, proud as we are about our inherent friendliness and ever-ready smiles. Oh, we smile all right. Oh, we are friendly. But we are never spontaneous in our conversations with strangers, we are never fired-up enough to say a casual hi or hello anywhere we go. Here, you do. This is what I like about America.

What I also like is the implicitness given to you that here in America your individuality is prized. You can be who you are here—for the most part, anyway—and no one in general bothers with you. (There are many exceptions, of course, some very deadly ones.) They show this individuality in many ways: in fashion, in a lifestyle choice, in a fearless raising of hands to question the teacher in the classroom. I once read somewhere that Americans may be lagging behind worldwide in the fields of science or mathematics, but they are number one in the area of self-confidence. This is true. This is a place of very confident people. I was startled by that in the very beginning, coming as I did from a society where strong statements of whatever kind are often frowned upon and “regulated” by some subtle measure. America it seems to me, and I know that I run the danger here of being naïve, is a place where you can … “blossom.” I cringe using that hokey word, but nothing else fits the idea I am trying to convey. This is a place where you can make yourself into a somebody if you really wanted to, regardless of where you come from. I think they call this idea as the American Dream, but I am also aware that this has been a much-sullied fantasy of late, considering right-wing hatefulness we get in the media, the recession, among other things. I see this most manifested in the number of the homeless that I see everywhere—another thing that also surprised me.

But still you can’t help but feel the possibility of becoming anything—it’s palpable in the air, a true democracy for the ways we can pursue individual fortune.

Labels: life, travel

[0] This is Where You Bite the Sandwich

Wednesday, October 13, 2010

3:09 AM |

Twenty Below

3:09 AM |

Twenty Below

By Paul EngleTwenty below, I said, and closed the door,

A drop of five degrees and going down.

It makes a tautened drum-hide of the floor,

Brittle as leaves each building in the town.

I wonder what would happen to us here

If that hard wind of winter never stopped,

No man again could watch the night grow clear,

The blue thermometer forever dropped.

I hope, you answered, for so cruel a storm

To freeze remoteness from our lives too cold.

Then we could learn, huddled all close, how warm

The hearts of men who live alone too much,

And once, before our death, admit the old

Need of a human nearness, need of touch.

Today is Paul Engle Day in Iowa City.

Today is Paul Engle Day in Iowa City. From his

bio in the Poetry Foundation website: "Born in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, poet Paul Engle received a BA from Coe College and an MA—one of the first in the country to include a creative writing thesis—from the University of Iowa. His thesis won the Yale Series of Younger Poets award and was published as the poetry collection

Worn Earth (1932). Engle began his doctoral work at Columbia University, and then received a Rhodes Scholarship, allowing him to study at Oxford University with the poet Edmund Blunden while earning his second MA. Upon returning to the US, Engle joined the faculty of the University of Iowa, where he became the director of the Iowa Writers’ Workshop soon after its founding, a role he held for 24 years. Engle shaped the program into the model it has become for other writing programs across the country and brought esteemed poets such as Robert Lowell, John Berryman, and fiction writer Kurt Vonnegut onto the Iowa faculty to teach the next generation of poets, including Donald Justice, W.S. Merwin, Philip Levine, W.D. Snodgrass, and many others. His influence on a generation of writers is celebrated in an anthology edited by Robert Dana:

A Community of Writers: Paul Engle and the Iowa Writers’ Workshop (1999). In 1967, with his wife, Chinese poet Hualing Nieh Engle, he co-founded the International Writing Program at the University of Iowa. Engle and his wife were nominated for a Nobel Peace Prize in 1976 for their work supporting international writers. Engle’s formally driven, elegiac poems explore themes of travel, allegiance, and family. Engle published more than a dozen collections of poetry during his career, including the bestselling

American Song (1934) and

Poems in Praise (1959), as well as a novel, a children’s book, and a full-length libretto. His memoir,

A Lucky American Childhood, was published posthumously in 1996. Engle edited numerous anthologies, including the

Ozark Anthology (1938),

Reading Modern Poetry (1955, with Warren Carrier), and

Poet’s Choice (1962, with Joseph Langland). He was the series editor for the O. Henry Prize from 1954-1959. Engle died in 1991, at Chicago’s O’Hare Airport, on his way to accept an award."

Labels: iowa international writers program, poetry, writers

[0] This is Where You Bite the Sandwich

Tuesday, October 12, 2010

7:54 PM |

Excerpt from "Fly-Over Country"

7:54 PM |

Excerpt from "Fly-Over Country"

[an excerpt from a story in progress]I have never been to Cedar Rapids. When you come from Milwaukee or St. Paul or Madison and are headed my way for whatever reason, Cedar Rapids will most likely be your portal mid-sized metropolis—the last sprawling stretch calling itself a city, with buildings more than five-stories high, before you get to the tree-lined, grassy-knolled avenues of my stout-hearted town, so stout it mistakes itself for a city.

But I came, tail between my legs, from Chicago. And settled some months ago in the staid suburban hug of Coralville, a football pigskin’s throw away from the academic wet dream of Iowa City. I had journeyed by car through Interstate 80, motoring past the exit signs to throw-away towns with the airy, borrowed names such as Joliet, Marseilles, Malta, Woosung, Ottawa, La Salle, Peru, Le Claire, Cambridge, Princeton, Milan—names which struck me as sad. Almost forlorn, like an empty promise.

On that trip, the ghosts of Chicago still after me, I had maneuvered my beat-up sedan, more than ten years old, towards one of those small towns just west of the Mississippi. It was a dump called Jaspers, with a seedy-looking strip mall at the center of things, with a Wendy’s that showed no signs of life. But it was the town with the nearest exit that could be had for a late lunch on the road, and I was hungry enough to eat a squirrel, which was compounded by the boredom of the landscape—endless stretches of cornfields, punctuated only by barns and silos. In Jaspers, I had a turkey breast and black forest ham sandwich from a sad-looking Subway stop tucked into a corner of a grocery slash gas station. An Indian girl curled my order with a thick Mumbai accent. She seemed frightened, or tired. The fluorescent lighting above her counter, which seemed to contain a scarce supply of the sliced mishmash of her sandwiches to-go, cast shadows below her eyes and made her look old. She gave me my total and her thank you spiel in a thick fog of sounds I could not understand, and I soon found myself back in my car, behind the wheel, munching away at the sandwich like an absent-minded dog. All I thought of was how the Indian girl seemed trapped, like a gerbil in a cage, in that horridly lit space behind the sandwich counter. It was not as if I felt sorry for her—I didn’t, but all I could think was how people could survive with lives like that, like a gerbil in bad lighting, muttering sandwich ingredients for a living.

In Coralville, I settled in the cheapest one-room apartment I could find that was decent enough, and found myself a job in Iowa City muttering the names of cocktails and cheap beer in a gay bar called Studio 13. It was in an alley off Linn Street. On Tuesdays, the town folk came in for the karaoke and the $3 draft beer. The rest of the weekdays, I rolled my eyes as the deejay spun dance music almost a decade old. On weekends, Saturdays for the most part, between ten o’clock at night and two o’clock in the wee hours of morning, I took off my shirt, flexed my biceps and pectorals, and played flirtatious bartender to the young college boys coming in, their eyes always darting around in the dim light, always hunting. The small space was a beehive of sound and frenetic dancing, the darkness animated only by glow sticks and laser lights and the incandescence of white skin off the twinkie boys showing off—with the sweet abandon only the desirable young could pull off—the promise of tactile desire. I had seen all these before, in various incarnations, manifestations, and all I could do was shake my head.

He came in one Saturday night. He looked almost out of place, a chinky-eyed man in his mid-thirties, with spectacles. His face was a wonderland of curiosity and amused disbelief it was almost comic. As if he had never seen men dance with other men before, as if he had never seen that much skin in the throng of writhing bodies in the worship of Kylie Minogue, or Madonna, or Lady Gaga.

He ordered a spritz of strawberry soda, no ice.

I raised one of my eyebrows and smiled. “Is that all you’re having?”

He flashed a nervous smile back at me, and said in an almost apologetic tone, “I don’t really drink.”

“Then why are you in a bar?” I said, my eyebrow still raised. I leaned towards him, my elbows on the counter, my face quite near his. I could feel his skin flushing.

“Oh.” He laughed a little. “I thought it was a good Saturday night to get away from my hotel room, at least for a while. I was tired of writing.”

I stared down at his lips. “So, you’re one of those Iowa writers.”

“Yes.”

That was all he said.

It was part of my job description to flirt just a little. It kept the drink orders coming, or so I was told. I didn’t mind. I liked flirting. I thought of it as a kind of sport. I thought of it as something you do to make other people feel better about themselves.

I was the Mother Teresa of flirtation.

“So maybe, if I play my cards just right, I’d probably end up as a character in one of your stories,” I said, curling just a hint of a smile to make my one dimple pop out.

“I…I suppose so,” he said.

“So I guess you’re here for research then.”

“You…you can call it that.”

“So, let’s say you’re really writing this story. And I am a character in it. What would you name him?”

“What’s your name?”

“Allan.”

“Allan is a good name for a character that’s a bartender.”

“And what does Allan the bartender do in your story?”

He looked straight at me all of a sudden. I could catch a glimmer in his eyes that weren’t there before. It couldn’t be drowned out by the stray brightness of a laser beam, or a nearby glowstick being sliced through the air by a dancer in frenzy. He said, in a pace that was deliberate: “Allan... Let’s make him a character with a past. Let’s say, he’s running away from something. Let’s say he’s from some big city somewhere. St. Paul, maybe. Des Moines, perhaps. Let’s just say Chicago. It’s far enough. And big enough. And familiar enough to most people. Let’s say he settles in a small place—like where we are now—where no one he knows can find him. Or so he thinks.”

Suddenly something about all this bothered me, but just a little. Still, I did my bartenderly motions, and proceeded to make his drink—a strawberry soda spritzer, no ice—and pushed the glass across the bar towards him, and told him, “Go on.”

He took his drink, and slowly sipped from it. “Let’s say Allan befriends this guy in the bar he’s working in, the guy looked a little lost, and so he takes him into a kind conversation, opens him up, makes him feel comfortable in the middle of all that dance music, all that noise and spectacle.”

“What’s the other guy’s name?”

“Tony.”

“Tony…”

“Yes, Tony.”

“What happens next to Allan and Tony?”

“Tony does not drink.”

“What did he come to the bar for then?”

“Perhaps he was bored. And it was a Saturday night. And the rest of the town was dead for the weekend. The only sign of life there was was in the bars.”

“And then?”

“They talk.”

“That’s it?”

“Tony takes him back to his hotel, just across downtown, near Hubbard Park.”

“And?”

“They have sex in his room.”

It was I who was flushing now. Still, I couldn’t resist wanting to know what could happen next, to this fictional bartender and his fictional friend. I felt my insides already too invested in knowing the rest of the story, whatever it was.

“And then?” I asked, trying to sound nonchalant.

“And then the next morning, they go to Cedar Rapids.”

“That’s 25 miles away.”

“It’s a good autumn day. The drive up Cedar Rapids would be something.”

“But what’s in Cedar Rapids?”

“There’s a good Filipino restaurant in Cedar Rapids.”

“Tony is Filipino?”

“I suppose he is.”

“So they’re going to Cedar Rapids to eat in a Filipino restaurant?”

“For lunch, yes.”

“And then?”

“Allan would fall in love.”

“Oh, come on. What about Tony?”

“Tony will break his heart.”

“Well, that’s something.”

“It’s something, isn’t it.”

“It’s something.”

He smiled, and then he downed the rest of his drink. Then he reached across the bar to shake my hand. The skin of his hand felt smooth, his fingers were long and steady. His grip felt both strong and tender.

“My name’s Henry, by the way,” he said.

And so it was that I found myself in Cedar Rapids the next morning.

[continued...]Labels: fiction, writing

[0] This is Where You Bite the Sandwich

Friday, October 08, 2010

1:01 PM |

There is No Memory

1:01 PM |

There is No Memory

There was this one night in my immediate past which I struggle to place in the mist of encroaching forgetfulness. I played that game of “last look” with the man I loved. He had lain there before me like a beautiful marble statue, unmoving, reclining quietly in the darkness that surrounded us. The ritual of remembering him I stole from the numerous Hollywood romances I’ve seen—there was the pained and overwhelming silence, the soft kisses, the touch of one’s lips, like a benediction, on choice spots on the lover’s face: both eyes, the tip of the nose, the bridge between the forehead and the nose, the soft intersection between the jaw and the neck, and finally—with the lightness of air—on the fullness of his lips. I am told this is how we make a cartography of people we love, lest we forget. But maps get lost, or become outdated. Mnemonics have no power over how the vagaries of life eventually govern us all.

Labels: life, love

[0] This is Where You Bite the Sandwich

7:21 AM |

The City of All Our Leavetaking

7:21 AM |

The City of All Our Leavetaking

Thinking back, more than a month ago, I thought it would be hard to leave the city I had grown up in. I’ve known this place most of my life, interrupted only by the occasional forays into foreign shores. A year in Japan, for example, and trips to India, Singapore, Thailand. How do you exactly say goodbye to home? Dumaguete has defined who I am, or so I had thought. And so, on my last day there, before I boarded the first of my many flights to middle America, I strained to look at it as if I was about to see it for the last time.

I thought that embedding it perfectly in memory would last me the considerable span of time that I would be gone from it. I thought that it would keep at bay the cold, unfortunate fingers of homesickness. (When I lived in Tokyo, for example, I would regularly race to this secluded teahouse adjacent a magnificent woods, and there, on a rock in the middle of a garden, I cried for home. Also, on Saturday midnights, I would bring to my bed a portable radio, where I snuggled away the wintry nights and tuned in to the only show in Tagalog in a Tokyo FM station, listening to songs by Sharon Cuneta and Imelda Papin. Then I’d cry myself to sleep. Thinking back now, I laugh at the entire drama. But homesickness was no laughing matter then. It was a disease that kept me from enjoying, wholeheartedly, the strange and unfamiliar culture I found myself surrounded then.)

I thought that I could just close my eyes, and conjure from the figments of thought that create our sense of place the details of what I knew as home and be transported back, so easily, to the old smells, the old textures of familiar things, the old sights that constituted a cartography of where I come from.

When I was ruminating on this, I was riding a tricycle from Robinson’s Place on a late Sunday afternoon. I just had coffee at Bo’s where I had tried to get some reading done—but succeeded only by one chapter, haphazardly processed, interrupted by a constant flow of friends and familiar faces all saying hello. When the tricycle made the right turn where the mall jutted at a much-trafficked intersection towards downtown, I could already hear, because of the intimate proximity of the city’s game cockpit, the cacophony of voices placing bets on various colored fighting cocks. It struck me that this intersection painted the perfect face for Dumaguete—a place slowly crawling into cosmopolitan modernity, yet stuck for the most part in barriotic old-fashionedness. Some people call this charming.

It’s not hard to set a place to memory, like etches on a stone tablet, although it may take some form of practice. The trick is to look at the familiar with the full weight of curiosity. Only then does it come across to you in a new way, since blindness is the usual side-effect of familiarity.

For example, passing by Hibbard Avenue, I looked at the laundromat beside the fairy tale kitsch of architecture that is known around town as the Christmas House, and nitpicked at the name. Wishy Washy it’s called. How witty. How cute and seemingly apt. But does the owner know “wishy washy” also means “indecisive”? Perhaps not. (In San Francisco, I stumbled upon a similarly named laundromat along Powell Street, and smiled.)

Then I considered that bricked corner that has Silliman Avenue bending over to Hibbard Avenue, and asked myself,

how does one make that one last lingering look at a beloved? By taking in the strangeness of that corner’s traffic of vehicles, and how the chaotic seems to be the sense of order that makes things flow. By taking in the new intrusion of a pharmacy where once we played “observing sidewalk life in an aquarium” known as Scooby’s. By taking in the ancient presence of the acacia trees; how they tower above us, and yet how we completely ignore them, we don’t even see anymore the glaring wounds they suffer as puny city officials have allowed the cutting of their limbs in the name of infrastructure maintenance. What else? There are other corners of the city I went to and committed to memory.

And then I leave the place. “Why do you have to leave?” somebody close to me asked me. “It’s just for a while,” I told her. “I need the break. I need to leave all this familiarity behind.” What I didn’t tell her was that it was suffocating me, it was making me less human, less productive. What I didn’t tell her was that I was trying to escape old ghosts and miserable people who can’t be too happy unless they make everyone else around them as miserable as they are. What I didn’t tell her was that to learn to love the place we have grown in, it is sometimes necessary to leave it for some span of time. Distance makes you more objective, makes you forget old hurts, makes you more philosophical (and accepting) of the place that holds the key to so much of who we are.

Days later, I also realized that so many of my friends were leaving it, we were like an exodus—Karl Villarmea to Chicago, Bing Valbuena to Sydney, Likko Tiongson to Tokyo, Hope Tinambacan to Stuttgart, Razceljan Salvarita to Bali, and many others—and we seemed to echo the same sentiment. It is necessary to leave sometimes, even for a short while. But I remember something Timothy Montes once wrote about Dumaguete, and our relationship with it: “Nothing happens [here]. The [newspapers] can’t find enough dogs bitten by men, everybody knows everybody, and one resorts to gossip in the face of the uneventfulness of leaves falling to the ground. Still, when one says goodbye, one never really leaves the place. The mild sadness grows within you and when you ask yourself what makes you hang around this place transfixed in time, you realize the irony of leaves falling to the ground. I love [Dumaguete]; that’s why I hate it. Like leaves falling to the ground, we are suspended in mid-air and never quite reach the ground until we learn to despise it.”

Labels: dumaguete, life, travel

[0] This is Where You Bite the Sandwich

Thursday, October 07, 2010

2:29 AM |

Excerpt From "There Are Other Things Beside Brightness and Light"

2:29 AM |

Excerpt From "There Are Other Things Beside Brightness and Light"

[a short story]

For Dev “Sunt lacrimae rerum et mentem mortalia tangun.”

—Virgil,

The Aeneid Detachment takes practice.

I once cared about a dog named Tibby. It was a white Pomeranian—one of those frivolous types of dogs that are easy to love because the busy brilliance of their thick hair reduces even adults to squealing children. Tibby—if I try to recall correctly—was a gentle soul, and he had eyes that seemed to see through me. I was a young boy, and he was my world—a yapping mass of cuteness that required devotion. I fed him, I bathed him. Tibby slept at the foot of my bed. Once, in a boring drunken episode, my father shot Tibby with his gun, because the dog barked too loudly and made him spill his beer on his shirt which barely contained his swollen gut.

After mother buried the animal in the backyard, near the garbage cans, which was shaded by a hollowed out acacia tree in the dark subdivision where we lived, I mustered some courage to ask father: “Why did you kill the dog?”

He didn’t seem to get that there was rage swelling in my little body. My father snorted, and then said, “Because I can.” He guffawed. His breath reeked of beer. Hell, I quickly knew, stank like this.

I remember that was the first time I’d ever felt pain; perhaps this was also the last. I was nine. Pain throbbed like an ancient truth, coming to the fore from the gut, ending as a strange tingling between my legs that surprised me, just for a moment. There was pain, and there was father looking at me like I was a mouse, a small, talking insignificance of a mouse. All I could see in the feverish anger that swelled my imagination was Tibby’s shattered head heaped upon my father’s decapitated body, blood dripping down its jaws and into the soiled beer-stained wifebeater my father wore that night—five years, eight months, and thirteen days before he died.

I had a hard-on. I remembered that most of all. At nine, I had a fucking hard-on.

Later on, in my quiet days, my imagination tries to spring on me the sound of a dog yelping, in that frightened drawn-out cadence that signals knowledge of pain. But I have learned to drown that out with the white noise of nothingness—a gathering blob of pure vacuum that settles in my head and sits in it like a strange dark dream.

And all I will ever learn to see from then on is the dark side to everything. In the end, I must confess this: I never loved Sarah. She was just my Saturday well spent. I told her that. “I can never love you,” I told her in the very beginning. She took that as an invitation to redeem me. It was her first mistake.

[continues...]

Labels: fiction, life, writing

[0] This is Where You Bite the Sandwich

Monday, October 04, 2010

4:30 AM |

In Your Head

4:30 AM |

In Your Head

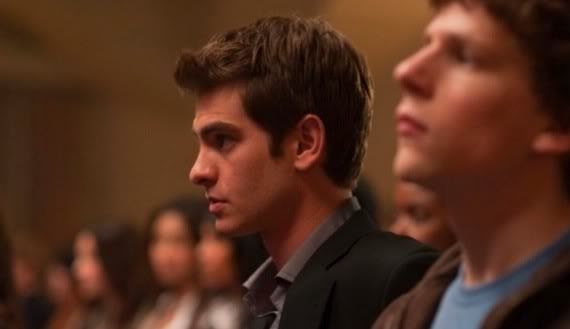

I honestly thought David Fincher's

The Social Network [2010] was a little underwhelming, given the rave reviews and the hype that was heaped on it even before opening day. When the lights came on in the movie theater at the Metreon, I stood up and walked home to my room in The Drake in San Francisco. It was very late, and it was off to bed I went, my only concern sleep. But I knew it was a well-made movie -- the direction was that of a master at the top of his game, the editing was taut and spellbinding, the writing was scintillating, the score understated but effective, the cinematography sly and somehow expansive in intimate ways, the acting superb -- but I found myself somehow underwhelmed, and maybe because I expected it to bludgeon me with its greatness. (But then again, like most great art, it's really all about subtlety.) It does not have the gimmicky and overscored finish of the top spinning in

Inception, just a soft petering off of an unfinished life, a subtle ending that brings in a reverse "asshole" bookend reference that began the movie, and a lonely Mark Zuckerberg repeatedly hitting refresh on someone's Facebook page, just to see if that someone will accept his friend request.

I expected the usual Hollywood fireworks. I forgot I was watching a David Fincher movie. Then again, maybe it was also because I watched it in a midnight screening, and my body was a little tired from all the walking I had been doing all over San Francisco. Which should not sound like such a big deal, but remember, the city is all about hills -- up, down, then up again, in boots I was trying to break in.

But God, this film has such staying power in your head. Because for many hours later, I kept thinking and thinking about it. I kept replaying certain scenes in my head. I kept going back, for example, to that lingering long shot of Mark walking across Harvard campus near the beginning of the film, after he got dumped and before spending an entire drunken night hacking and making code that would soon become his Internet revenge against all Harvard women. And I kept telling myself,

it's all there, in that lonely walk across campus. And I kept remembering certain snappy lines of dialogue, all of Aaron Sorkin's zing like lightning in a bottle. And I kept hopping from one Internet article to the next, hoping for more insight into this film. And people like me are legions online.

It's a great movie. The best movie I've seen this year. It crawls under your skin.

[0] This is Where You Bite the Sandwich

Sunday, October 03, 2010

8:08 PM |

I Left My Heart in San Francisco

8:08 PM |

I Left My Heart in San Francisco

Labels: life, photography, travel

[0] This is Where You Bite the Sandwich

GO TO OLDER POSTS

GO TO NEWER POSTS

8:30 AM |

Excerpt from "The Kitchen Goddess of Dogpatch"

8:30 AM |

Excerpt from "The Kitchen Goddess of Dogpatch"

3:46 PM |

Silence, Stillness, and Connection in a Crumbling World

3:46 PM |

Silence, Stillness, and Connection in a Crumbling World

10:54 AM |

The Things We Do Here

10:54 AM |

The Things We Do Here

7:24 AM |

My Own Private Paris

7:24 AM |

My Own Private Paris

9:15 AM |

Strings Attached

9:15 AM |

Strings Attached

9:11 AM |

No Chimes Here

9:11 AM |

No Chimes Here

12:24 PM |

Two Views, One Roscoe's

12:24 PM |

Two Views, One Roscoe's

2:02 PM |

In Leo's Room

2:02 PM |

In Leo's Room

7:10 AM |

Murdering the Humanities

7:10 AM |

Murdering the Humanities

5:06 AM |

At Home in the Beginning of Things

5:06 AM |

At Home in the Beginning of Things

3:58 AM |

Nostalgia is Dead

3:58 AM |

Nostalgia is Dead

5:11 AM |

Carving Out Time and Space in the Midwest

5:11 AM |

Carving Out Time and Space in the Midwest

3:35 AM |

A Jet-Lagged Person's Guide to Knowing America

3:35 AM |

A Jet-Lagged Person's Guide to Knowing America

3:09 AM |

Twenty Below

3:09 AM |

Twenty Below

7:54 PM |

Excerpt from "Fly-Over Country"

7:54 PM |

Excerpt from "Fly-Over Country"

1:01 PM |

There is No Memory

1:01 PM |

There is No Memory

7:21 AM |

The City of All Our Leavetaking

7:21 AM |

The City of All Our Leavetaking

2:29 AM |

Excerpt From "There Are Other Things Beside Brightness and Light"

2:29 AM |

Excerpt From "There Are Other Things Beside Brightness and Light"

4:30 AM |

In Your Head

4:30 AM |

In Your Head

8:08 PM |

I Left My Heart in San Francisco

8:08 PM |

I Left My Heart in San Francisco