This is the blog of Ian Rosales Casocot. Filipino writer. Sometime academic. Former backpacker. Twink bait. Hamster lover.

The Boy The Girl

The Rat The Rabbit

and the Last Magic Days

Chapbook, 2018

Republic of Carnage:

Three Horror Stories

For the Way We Live Now

Chapbook, 2018

Bamboo Girls:

Stories and Poems

From a Forgotten Life

Ateneo de Naga University Press, 2018

Don't Tell Anyone:

Literary Smut

With Shakira Andrea Sison

Pride Press / Anvil Publishing, 2017

Cupful of Anger,

Bottle Full of Smoke:

The Stories of

Jose V. Montebon Jr.

Silliman Writers Series, 2017

First Sight of Snow

and Other Stories

Encounters Chapbook Series

Et Al Books, 2014

Celebration: An Anthology to Commemorate the 50th Anniversary of the Silliman University National Writers Workshop

Sands and Coral, 2011-2013

Silliman University, 2013

Handulantaw: Celebrating 50 Years of Culture and the Arts in Silliman

Tao Foundation and Silliman University Cultural Affairs Committee, 2013

Inday Goes About Her Day

Locsin Books, 2012

Beautiful Accidents: Stories

University of the Philippines Press, 2011

Heartbreak & Magic: Stories of Fantasy and Horror

Anvil, 2011

Old Movies and Other Stories

National Commission for Culture

and the Arts, 2006

FutureShock Prose: An Anthology of Young Writers and New Literatures

Sands and Coral, 2003

Nominated for Best Anthology

2004 National Book Awards

10:52 PM |

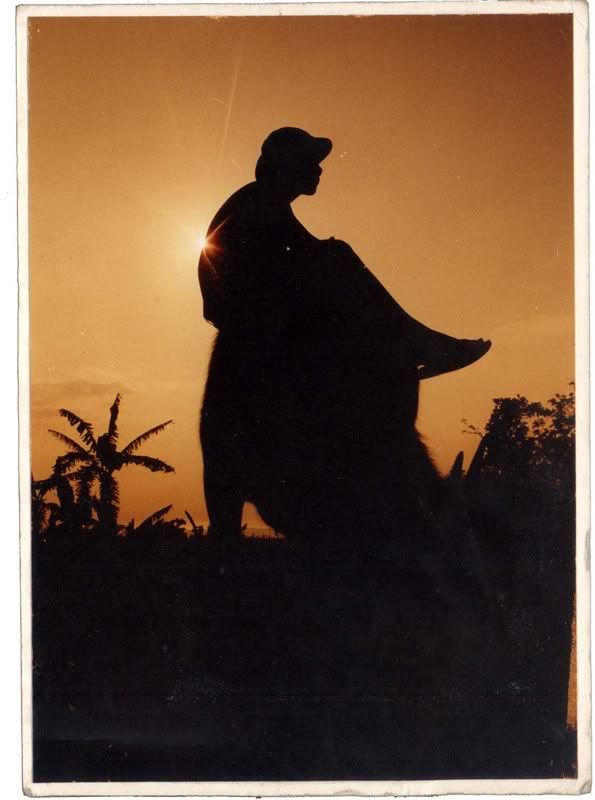

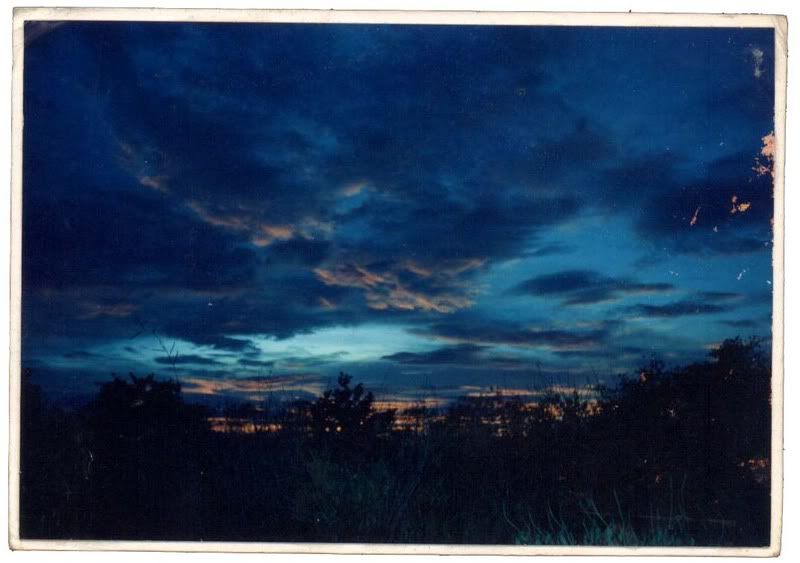

Old Photographs, and Dr. Albert Faurot

10:52 PM |

Old Photographs, and Dr. Albert Faurot

Sometimes, when Takami could not find a job, he would cross two mountains on foot to the seashore to dive for clams. "No one taught me how to swim; necessity taught me. I sometimes carried two big sacks of clams on my shoulders over the two mountains back to my town and exchanged them for salt or rice. I did this kind of thing to support my family."

To find work or to earn extra money, Takami says he willfully cheated and lied. An instance of this occurred in 1951 when he was in Kobe: "One day I found from the classified ads of the Mainichi English newspaper that a missionary at Kobe College was looking for a cook. I thought that this would be the right kind of job and that I would try it. Opportunities come to us unexpectedly, and we have the freedom to seize them by stepping forward." So Takami had an interview with Professor Albert Faurot, an American missionary from Kansas who taught music and art at the Christian-run Kobe College. Faurot had just arrived from China, where missionaries were being evacuated in the wake of the communist takeover in 1949. He was unmarried and lived by himself.

"I learned some English in high school before the war," Takami says, "so I could handle some conversation. And I said [to Faurot] that I could cook. He was desperate. He was a single man and even today I think he doesn’t know how to make coffee."

"Okay," Faurot said, "come back tomorrow and you will start."

"That is the time I told a lie," Takami says, "that I was a cook. He believed me." But Takami adds that he did have some experience cooking in the Zen temple. "The monks took turns cooking but mostly they just watched the rice cook," he said. Then, after the war, Takami worked for six months for an American military family. He learned to bake biscuits and fry eggs and bacon. "But I never actually saw a cookbook," he says, and he certainly did not know how to plan a menu.

On his way home from the interview with Faurot, Takami went to a big bookstore in Osaka and bought himself a copy of The Fannie Farmer Cookbook. Every night, with the help of a dictionary, he translated new recipes into Japanese. "For some time I never served (Faurot) the same kind of breakfast or dinner," Takami says. "I think that, to this day, he believes that I’m a professional cook."

Working for Faurot, Takami’s life began to change: "I saw that he trusted me. When I said I was a cook, he said, ‘Okay.’ He fixed a salary and hired me. When I went with all my dirty clothes and one pair of torn rubber boots to wear, he said, ‘Okay, you will start living with me in the same house.’" Faurot fixed up a room for Takami next to his own and bought him a new desk, chairs, curtains, and bedding. "This was the first time in my life that I had a private room." Next, Takami says, "he gave me a large amount of money and a small notebook to keep accounts. He said my responsibility was to keep the house, plan meals, write menus, do the shopping, keep all records in the book, pay the bills, and report only once a month to him. I never met this kind of person before. I was ready to cheat and I knew how. But when I experienced such trust, this really began to change my own life. I couldn’t cheat this person. I began to trust this person, and I also began to trust myself."

Faurot never asked Takami to come to church with him. But Takami did see Faurot reading the Bible in English and going to church every Sunday. One day Takami asked Faurot to take him to church -- to the Japanese church. Takami was so impressed by the sermons preached by Dr. Hiroshi Hatanaka, the president of Kobe College, that he began to attend regularly. "I was so used to leading a very poor life that I thought the [Japanese] Bible was something I really shouldn’t spend money on." So he got himself a free copy of the Bible from a missionary, a small, pocket-sized New Testament that he read with the help of a dictionary. He began to attend Bible study. "When I came to the Gospel of John," he says, "this particular book spoke to me directly. Many times I had a very strong spiritual experience." And when he came to the story of Paul, he says "all the life that I had thus far experienced became meaningful." After that, Takami asked the pastor to let him join the church and to be baptized.

Eight months later, Faurot moved from Japan to Silliman University in Dumaguete City in the Philippines. Before leaving Japan, he arranged work for Takami with another missionary and also asked friends in Nebraska to help raise funds to further Takami’s education in the United States.

Labels: art and culture, people, photography