This is the blog of Ian Rosales Casocot. Filipino writer. Sometime academic. Former backpacker. Twink bait. Hamster lover.

The Boy The Girl

The Rat The Rabbit

and the Last Magic Days

Chapbook, 2018

Republic of Carnage:

Three Horror Stories

For the Way We Live Now

Chapbook, 2018

Bamboo Girls:

Stories and Poems

From a Forgotten Life

Ateneo de Naga University Press, 2018

Don't Tell Anyone:

Literary Smut

With Shakira Andrea Sison

Pride Press / Anvil Publishing, 2017

Cupful of Anger,

Bottle Full of Smoke:

The Stories of

Jose V. Montebon Jr.

Silliman Writers Series, 2017

First Sight of Snow

and Other Stories

Encounters Chapbook Series

Et Al Books, 2014

Celebration: An Anthology to Commemorate the 50th Anniversary of the Silliman University National Writers Workshop

Sands and Coral, 2011-2013

Silliman University, 2013

Handulantaw: Celebrating 50 Years of Culture and the Arts in Silliman

Tao Foundation and Silliman University Cultural Affairs Committee, 2013

Inday Goes About Her Day

Locsin Books, 2012

Beautiful Accidents: Stories

University of the Philippines Press, 2011

Heartbreak & Magic: Stories of Fantasy and Horror

Anvil, 2011

Old Movies and Other Stories

National Commission for Culture

and the Arts, 2006

FutureShock Prose: An Anthology of Young Writers and New Literatures

Sands and Coral, 2003

Nominated for Best Anthology

2004 National Book Awards

7:18 AM |

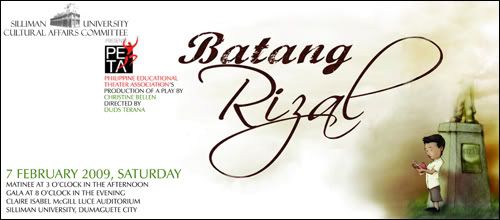

PETA Presents 'Batang Rizal' This Weekend in Dumaguete

7:18 AM |

PETA Presents 'Batang Rizal' This Weekend in Dumaguete

If you were Jose Rizal as a kid—say, 10 years old, snotty, sickly, sensitive, a wisp of a boy in a household full of grown-up women—and you happened to learn, by some cosmic fluke, that in time you’d do great things and become a National Hero, you’d be elated, wouldn’t you? The monuments erected in your honor, the books written about your life, the countless streets bearing your name, even your likeness in a friggin’ peso coin! Music to your teeny-weeny ears, right?

What if, however, that ego-stroking peek at the future comes with news that you’d also end up dead, cut down by firing squad one morning, for all your so-called grand, heroic exploits? Would you still want to be a hero? Would you still choose the path to glory, or would you rather retire to a farm in Calamba, raise a family, and live the rest of your life in obscure but fulfilled quietude?

A question worthy of Nikos Kazantsakis and Martin Scorsese, if you think about it. They posed a similar conundrum in “The Last Temptation of Christ,” which had a very human Jesus—knowing what he knew was coming—questioning right up to his penultimate breath whether the agony and death he was to go through were all worth it. (As you know, the Bible ruined the suspense with spoilers.)

Look at me—lost in Heavy, Serious Thought, brow all furrowed and lips all grim, when I’m actually talking about... a children’s play. That’s right, the thing that got me all hunched up on heroism, choice, destiny, crystal ball-gazing blah blah blah is a show meant for kids (though not exclusively, thank God or the muses for that): PETA’s current production of “Batang Rizal.”

I hope I didn’t scare anyone with my little bout of, ah, mental onanism. That’s just me when it’s past midnight and I’m hungry and oxygen-deprived. The show is in fact one bright, funny, fizzy ball, a “message” play that goes easy on the Big Idea and lets the story, an imaginative time-travel adventure performed by a winning set of young actors, do the job instead. The scene where the kid Rizal first hears, to his horror, that he’s going to die in a strange place called the Luneta actually plays out as one of the show’s high points—a hilarious moment of unexpected revelation that, on the Sunday afternoon I watched, the mostly-student audience lapped up with gusto.

You might say that “Batang Rizal” adheres to the classic Mary Poppins philosophy: you know, that a spoonful of sugar helps the medicine go down, never mind the calories. I’m happy to report that this entertaining play is topical without being preachy. Its ultimate take-away thought—that there’s a little bit of Rizal in all of us—is actually hard to convey without Mariah popping up in the background and warbling “Hero” as the default soundtrack.

However, playwright Christine Bellen and director Duds Terana skirt this problem by ditching the hagiography altogether. The Rizal that emerges from their ministrations is delightfully alive and accessible, and that humanity helps the play put its point across simply and clearly, in a manner that refuses to talk down to the kids while remaining engaging to the grown-ups in the audience.

What’s praiseworthy about “Batang Rizal,” at least to me, is that, by knocking the hero off his lofty pedestal, it brings him back to ground level where we can size him up more rigorously. Mike De Leon attempted something similar with “Bayaning Third World.” As with that movie, I came away from this play with my view of Rizal both reinvigorated and reaffirmed.

In contrast to Lola Basyang, Batang Rizal consists of one unified narrative, which is a reason it is the superior, more satisfying work. Written also by Christine Bellen, the play follows the story of Pepito Waling-Waling, a student at one of our many schools named after the national hero, as he journeys back to Rizal’s time and brings the boy who isn’t yet a hero but is already destined for greatness to the present. (Pepito’s time-travel device is that instrument of imaginative wonders: a book.) The narrative is interspersed with the writings, mostly poems and tales, of the young Rizal.

Mel Bernardo’s set looks like a blown-up student’s desk, consisting of massive pencils and books. A space in the far wall like a lined sheet of school paper becomes a screen for video work by Don Salubayba and the Anino Shadowplay Collective. Ron Ryan Alfonso’s costumes are again playfully vivid. The students wear bright yellow uniforms with candy-colored stripes. (These would be welcome in the real world, where khakis and whites reign in bland supremacy.)

The play is a richer experience than Lola Basyang also because it traverses a broader spectrum of emotions. Though largely a comedy, it also has poignant moments: Pepe visits his mother, Donya Lolay, in jail (she spends more than two years there on trumped-up charges), and he recites a poem to her as she listens, attentive and sad. Pepe’s older brother Paciano desperately exhorts the young boy to study hard in Ateneo and not waste his gifts. Brief episodes with stern friars remind us of a grim part of our history. Young though the boy is, he is already awakening to the harshness of the world. (Dudz Teraña’s astute direction keeps the shifts in tone finely modulated.)

Part of the play’s humor derives from its doing something most others find unthinkable: poking fun at the national hero. How often have we seen plays or films about him or his work that groan under the weight of their own solemnity? Pepe is just a little vain. Upon seeing a portrait of his grown-up self in Pepito’s school, he grins and says, “Es muy guapo!” Pepito replies, “Sabi na nga ba, mayabang ito, eh!” In a skit reenacting Rizal’s execution, a student turns to the audience to recite his famous farewell poem, forgets the lines, and substitutes wildly inappropriate words. When he is scolded for it, he says, “Mamamatay na nga, tutula pa! Meron bang ganoon?”

Again the PETA ensemble turns in a strong, assured performance. Not only that: I watched both productions on the same day, and most of the performers in the morning show of Lola Basyang appeared in Batang Rizal in the afternoon. It’s a testament to the skill of Bernah Bernardo, Joann Co (as both Miss Tangolang the teacher and Pepe’s mother), and Wylie Casero (the mayor and Pepe’s brother) that they move easily from cartoonish humor to tenderness and as deftly make us laugh as make our hearts heave. And when it comes to making us laugh, Bernardo and Casero do it best. Bernardo plays Tangolang as a garish sequined butterfly, one part schoolmarm and three parts palengkera. Casero’s Mayor Rapcu (say the name quickly several times to get the joke), who donates a monument to the school, smiles with unctuous pomposity and mauls the English language with clueless impunity while wearing perhaps the most hideous barong tagalogs ever seen on a public stage. The gaudy bling is the cherry on top. Other standouts include Abner Delina, whose preternaturally youthful countenance and voice make him perfect for the title role, as well as Kitchie Pagaspas, Joan Bugcat, and Carlon Matobato as Pepito’s feisty classmates.

The play has a conventional moral about everyday heroism, yes, and it even comes bundled in a song (Vince de Jesus provides the music and lyrics), but it goes down smoothly with so many spoonfuls of sugar. Wholesome in the best sense yet daubed with welcome irreverence, Batang Rizal is infused with something else that young and old will have no quarrel with: childlike wonder.

Labels: art and culture, cultural affairs committee, dumaguete, negros, silliman, theater