Wednesday, May 30, 2012

11:13 PM |

The Romantic Pessimist

11:13 PM |

The Romantic Pessimist

Truth to tell, I might be a romantic pessimist. I think my worldview basically springs from two metaphors I've read about: (1) from Buddhism, we learn that from the moment we are born, we start dying; (2) and from physics, we learn that we are all made of atoms, and since atoms consist mostly of empty space, we are essentially nothingness on two legs. Fascinating, right? We are emptiness that start dying out the moment life happens. What lovely paradox.

Life is fundamentally sad, I think. But it's what makes the happy moments really happy. :)Labels: life

[0] This is Where You Bite the Sandwich

Tuesday, May 22, 2012

5:07 AM |

The Visualist of Common Sense

5:07 AM |

The Visualist of Common Sense

Part 9 of the Dumaguete Design Upstarts Series

Looking at the paintings of Paul Benzi Florendo, one immediately recalls the raw power of the works of the young Jutze Pamate or Mark Valenzuela or Razceljan Salvarita—all of earnestness and strangeness and sureness of vision that mark what may be the beginning of a fantastic career in the visual arts, right at its rawness, without strings or politics or life’s hard bargains. To look at Benzi’s paintings and see how they pulsate is to quicken once more life from the tired old critical bones, slaying the old pronouncements that “visual art in Dumaguete is dead.”

It’s certainly not.

That it is in some sort of doldrums may be something that cannot denied. But there are others like Benzi springing from an increasingly bustling art scene in Dumaguete. (That is, if “bustling” is the word.) Collectively, they constitute some hope, enough for the city to recall its prime as Visayan capital of art. The most exciting among them include Stephen Abanto, Nabil Padilla, Jess Andrew Abode, Sabrina Skye Benito, Kristine Jul Oliva, Ramon Adonis Catacutan, and Hans de Barras—and in their last group show together, for the

Third Horace B. Silliman Art Exhibit held last March, some showed a brilliant command of the artistic that went beyond the pale of the expected and the humdrum: I remember a guitar stripped, dismantled, reset, and transformed into a kind of Rorschach test; a series of still lives and what-not—a snake with a gun among them—that seemed to put some strange edginess into the representational; a set of skulls from different sorts of material that put a hint of danger to the domestic; an installation of clay and wire figures “at play” with kites that married wit with the whimsical. These were fantastic pieces by some of the city’s young artists, and one could only wish to see more of what they could do beyond plates made for classroom exercises, beyond the requisite demands of academic exhibitions. That most have not entirely burst out of their confines and rocked the city beyond the comforts of campus life is a little beyond my ken—but perhaps they are only cocooning?

Paul Benzi Florendo

Enter Paul Benzi Florendo. A few months ago, in the makeshift exhibition walls of Canto Fresco, which is owned by the visual artist Babu Wenceslao, he debuted with his first solo exhibition—something he called

What Ya Think? The show, small though it was, featured ambitious art with a nod to the soft, strangely tender (if also unsettling) surrealism of René Magritte—but with wit completely Mr. Florendo’s own. There’s the blue teddy bear with the old man’s face, dragging a toy cart with square wheels, in diagram; there’s the masked boy astride a snail, bullhorn in hand; there’s the similarly bullhorned girl, eyes masked or pixelized, riding a giant rabbit; there is the army of boxy androids with human faces, minus the eyes, deep in empty thought-balloons; there’s the strapping youth with the baseball cap, looking up into the rainbowed sky, boxed in by some invisible diagram that include a hovering satellite… It is all very strange, and all made to make you ask—“What do you think?” The question is subtly provocative, and asks much of the viewer in terms of what they put

into the pictures.

It is the painting “Egghead” that strikes me the most though. It shows a gigantic egg hovering in an emptiness of azure, cracked in places, and through the bigger holes punched by the cracks, we see various parts of a human face—nose, lips, ears, eyes—asymmetrical, disembodied, and whole at the same. And all that, afloat, like a beautiful threat.

What do you think?

Egghead by Paul Benzi Florendo

“I always want to make people think hard when viewing my works,” Mr. Florendo explained. “I do not want the audience to just see my painting and think, ‘Oh, it’s nice,’ or conversely, ‘Oh, that’s stupid’—and just stop there. I want them to recognize something beyond what is obvious. I want them to perceive how I see life or how I tell a story of moments through my paintings—and perhaps relate these to their own lives.”

But what he also wants is a workout of sorts for his potential viewers. “I want them to feel as if their brains are going to burn up trying to think too much,” he said, “or perhaps even ultimately explode, especially when they realize that too much thinking did not have to done in the first place. I want people to be able to also use plain common sense, which is rare these days. I want to spark creativity in my viewer’s minds, and perhaps cause them to be artistic in their own ways.”

Which is perhaps putting too many eggs of expectations in one basket, but one admires that ambitious reach in the young artist: to seize that fabled opportunity to reach into the minutiae of a viewer’s head, and transform thinking through art.

What do you think?

But regardless of my mention of Magritte, Mr. Florendo does not claim to have influences in the way he marks his art. He reaches out, instead, to the common “influence” of what surrounds him: “My influences are the people around me doing what they normally do,” he said. “May it be wiping the table, playing in an orchestra, taking photos, typing on a keyboard, chewing gum, snoring, running, giving a sermon—you name it, these simple things give me a lots of ideas that can certainly be turned into something artistically complex. It’s like a simple cycle: I take ideas from what I see around me, then I give it back to the world through my paintings.”

And if this indeed is a start of something bigger, artistically speaking, what does the future entail for him? “I always wanted to do work which many people can relate to, or at least that they will be blessed by my work. But something I have always wanted to do is make people interact with my art in certain ways.” But it is that first wish for relatability that he wants the most. “I hope to achieve something big which people around me can recognize and be able to relate to. Even the simplest of people.”

Which makes common sense.

Labels: art and culture, dumaguete

[0] This is Where You Bite the Sandwich

3:29 AM |

The Three Virtuosos of the Photographic Eye

3:29 AM |

The Three Virtuosos of the Photographic Eye

Part 8 of the Dumaguete Design Upstarts Series

Is there a glut of photographers in Dumaguete? Without batting an eyelash, my answer is yes—and not just in Dumaguete. The delusion of photographic skill is everywhere, and the evidence is flooding the feeds of our Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Tumblr, Flickr… I’ve said it before. The exploding number of shutterbugs is a phenomenon directly proportional to the increasing democracy of digital photography, and it has become a joke in photography circles that these days anyone with an SLR seems to think he can saunter into the world and proclaim himself a “photographer.” That the vast majority do not call themselves thus is an act of mercy by the universe—amateurs thankfully in acknowledgment of their limitations. For a few that do, their sheer number often threatens to overwhelm the integrity (and asking price) of the profession, leaving the serious professionals in ridiculous competition with wannabes who invariably take commissions with a grain of salt, but don’t often deliver. As a result, the price for photographic talent may be bottoming out.

Of late, we get waves upon waves of photographic blahness—ad infinitum and ad nauseum—of leaves and flowers, sunrises and sunsets, women in bikinis, men in briefs. Most of these are slyly tweaked in Photoshop (or, heavens, Instagram) to approximate some glossy finish. Truth to tell, one or two of these pictures are beautiful all right, an accident of timing and angle; but in the context of body of work, the eye—the crucial eye—sans Photoshop is missing. Nothing draws you in beyond the initial “hmmm.” There’s no magic.

In the ocean of photographers in Dumaguete, a few do stand out. There’s Kat Banay and Hersley Ven Casero, whom I have featured in this series separately. In the front ranks, you will find Mikko Lim, DX Lapid, Clee Andro Villasor, Kim Cuevas, David Jules Mamhot, Zon Lee, Alma Zosan Alcoran, Paul Benzi Florendo, Darrell Bryan Rosales, Jerick Hernani, Aris Ramiro, Charlie Sindiong, Jaysie Tayko, Phil Calumpang—and I may be missing others, but this is by no means an exhaustive list.

Yet I keep turning to the works of three young men whose technical proficiency and hard-earned professional integrity seem to coincide with the gift of the elusive eye: the photographs of Luigi Anton Borromeo, Brian Arbas Rimer, and Urich Calumpang seem to me to be the prime examples of budding artistry in overarching mastery of medium. Whether with a regular still camera, a video, or an iPod, these three have exhibited an uncanny understanding of photographic language. They have demonstrated that it is not enough to own the proper expensive gadgets and certainly not enough to know the tweak buttons of post-processing applications. Great photography is the telling of an evocative story—and the best of them, for the lack of a better word, move you. The works of these three have moved countless people—and they know how to tell a story.

For all three, a childhood brush with the camera proved to be the push to a life-long drive to perfectly capture something of life. For Mr. Borromeo specifically, the interest had childhood roots, but it was also a late-blooming love affair. “Film was expensive,” was his explanation. He was already all of 20 years old when he really started taking photography seriously, digital this time. But the fascination had always been there; and the motivation, too. “I’m always motivated to shoot,” he said. “I get that from Ansel Adams who once said, ‘The single most important component of a camera is the twelve inches behind it.’”

Luigi Anton Borromeo

And shoot he does, although the whole seriousness of the craft was something he had to get used to. “Intimidation is my weakness,” Mr. Borromeo said. “I easily get intimidated when I’m in a crowd of photographers who have greater experiences and have better equipment than I do. I own an entry-level digital reflex camera. So the only way I can compensate is to do my best to make a picture seem like it was shot on an expensive camera.” Which is perhaps the perfect retort to anyone who believes gadget trumps over talent. (And there are certainly a lot of them.)

Portrait of Kylie Montebon by Luigi Anton Borromeo

Mr. Borromeo’s forte is environmental portraiture. “I was inspired by Joe McNally,” he said, “especially in how he lights his subjects. He does this in very creative ways. He utilizes ambient and artificial lights very well, making the picture interesting. His technique gives his subject more dynamism and depth, without exactly going overboard.” His portrait of Kylie Montebon is a good example of that influence—lighting and depth and texture and subject’s beauty in a great mix, it cannot help but tell a story. This is not merely a girl posing. This is a girl with a story captured well—a hesitation in full make-up, wary and unfeeling at the same time. That she caresses a tree, its texture barely there, adds to an effect of obliqueness.

Brian Arbas Rimer, on the other hand, seems to have found firm footing in both still photography and video—and his own love affair with capturing image also has its roots in childhood. “My dad used to bring his camera everywhere we went, and we kind of got used to the idea of photographing every detail of our family vacations,” he said. “I got my first film camera when I was 7, and since then, I’ve fallen in love with photography.” He started devouring the pictures of Scott Kelby and the photographs he saw in National Geographic. He started aiming for what he saw in them: “a perfect shot, where one image perfectly captures an entire event.” That calls, of course, for an instinctive feel for the grand moment that is often fleeting, which is something that will inform his future work.

Brian Arbas Rimer

But Mr. Rimer’s real education sprang from encounters with local wedding photographers—Dino Lara, Rock Paper Scissors, Paul Vincent, and Nelwin Uy. “I noticed that they concentrated more on people’s expressions rather than on technicalities,” he said. The technicalities, for him, can often prove to be cumbersome if allowed to overwhelm the shoot. Mr. Rimer prefers instinct above all, especially the instinct to capture emotion in people that, in his own words, “can be universally understood.” “Photography,” he once said, “is the language I use to translate other cultures.”

One sees all these in his collective work that seems to celebrate the candid. “I like to take a step back and let things happen on their own rather than setting up or posing a picture,” he said.

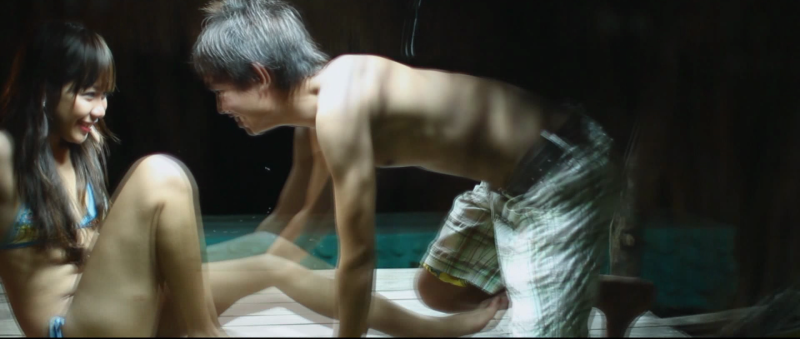

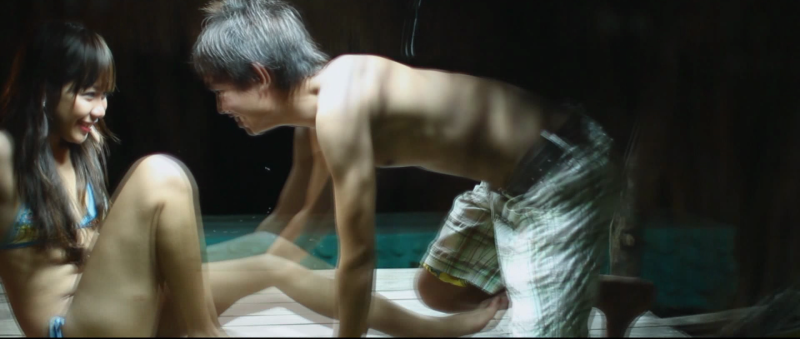

Scene from Amor y Sangre by Luigi Anton Borromeo and Kim Cuevas

With Mr. Cuevas, Mr. Rimer has also done cinematography for some local short films, notably a NORSU-produced film titled Amor y Sangre. There is a sequence in the film—of two lovers being amorous in a beach-side cottage at night—that jumps at me for the inventiveness of its tracking shot which at once relays playfulness and illicitness requisite in the scene. “I started to get interested into cinematography not that long ago since HD movie recording came out,” Mr. Rimer said. “Bringing movement to pictures was something totally new for me, a still photographer. First it started out as something I did for fun, until I began learning more techniques. It soon required new equipment, and once again it became another passion.” Of Mr. Rimer’s forays into film, he cites as influences the documentaries of Jason Magbanua, Threelogy, Mayad Studios, Chase Jarvis, and Vincent Laforet.

For Urich Calumpang, photography began as a holiday gift when he was younger. “I got my first camera from my mom as a Christmas gift,” he said. “It was a Casio point-and-shoot camera, and I started taking pictures of the usual flowers ands sunrises and sunsets. The usual macros. What was just there, I shot. I was 17. I had that camera for around a year, and soon it broke. So I got another camera, which was still a point-and-shoot one, a Kodak. But I wasn’t satisfied with my pictures, and so I worked abroad, in California, for two months, and saved up for a better camera. Which was a Canon 550D, which I use until now.”

Urich Calumpang by Francis Silva

That was when he started shooting for real: people and streets and assorted events. “It was mostly just everything I saw that interested me,” he said. “I’ve learned a lot from the photographs of Ansel Adams. And locally, the works of Hersley-Ven Casero. I soon met the most awesome photographers who mentored me and taught me a lot of things, and helped me. I learned the ethics, I learned how to take solid shots, how to cover events, how to dress appropriately. There’s Greg Morales. He’s like my second dad. And I’m most thankful that we got to know each other.”

For Mr. Calumpang, the process of taking good photographs is just letting the creative juices flow. “I have learned not to suppress it. It’s there, within you. That flows in you,” he said. And so, every single day, he brings with him anything that has a camera—a phone, an iPod, whatever. “Wherever I go, I’m always ready to take pictures of things, everyday things that people often take for granted. Some of the most wonderful photographs I’ve gotten come from the most common things usually taken for granted. But my process is quite simple: I feel it, the potential photograph. When you look at something, and you picture it in your mind…when you are able to think of that something, you can actually take that very picture.”

His regular commissioned photos, always without Photoshop, have a sparkling crispness to them that belie an instinctive feel for moment and light and angle. But when he goes for a stylistic bent, he bends color to a 70s Polaroid feel. “These photos give me that nostalgic feeling,” he said, “and a sense of euphoria.” Which may be understandable for somebody who is fond, musically, of standards and the whole Beatles repertoire. “I’ve always wondered what it must have felt like, to live in that age, when my music idols were actually very much a part of the era,” he said. And in wonderment, he tries to recapture an era with photography.

And so we thus know that Mr. Calumpang has his own stylistic quirk, often best captured in his experiments with Instagram, using his iPod.

Pigeons 2, taken with Instagram, by Urich Calumpang

But his fascination for the extraordinary and the symmetrical in the common perhaps defines him best as a photographer—and you see that in his shots of architectural detail, of lines, of geometrical shapes. All these from everyday objects and scenes, of course. This appeals to the obsessive compulsive in him. “I love symmetry. I love it because it has balance, it creates a sense of completeness, which best describes my personality as an O.C. guy. I put more emphasis on balance, and seeing things that are in place makes me at ease,” he said.

A sense of balance, ease, and symmetry. A feel for light and ambience. An instinct for moments. Perhaps these are the very ingredients that define the photographic eye. In the works of these three men, we have an embodiment of the very same things.

Labels: dumaguete, film, negros, photography

[0] This is Where You Bite the Sandwich

12:46 AM |

The Designer of Film Sound

12:46 AM |

The Designer of Film Sound

Part 7 of the Dumaguete Design Upstarts Series

Think of your favorite film, and you think of the images that compose the story. The best ones—a marriage of skillful direction and a deft cinematographic eye—give film an almost tactile heft. The best of film, after all, is sorcery in pictures in the service of story. Think of the films seared into your memory. There’s the little girl in the red dress in Steven Spielberg’s black and white

Schindler’s List. There’s Neo evading bullets in a space-bending ballet in The Wachoswki Brothers’

The Matrix. There’s the smoke billowing from the passing trains, to engulf the space of the illicit love affair of our lovers in David Lean’s

Brief Encounter…

You behold these choice mise en scenes, and you know, somehow, what their movies are specifically all about. Films are indeed constructed from a grammar of images. But sound—

and music—underlines their emotional tone.

Think about your favorite films again, and at the back of your heads, the refrains of their scores somehow become their anchors: consider John Williams’ shark-baity suspense in Spielberg’s

Jaws, Henry Mancini’s longing for a world that understands lost souls in Blake Edwards’

Breakfast at Tiffany’s, Bernard Herrman’s slashing sounds of terror in Alfred Hitchcock’s

Psycho, the Bee Gees’ disco beat underlining a dreamer’s hopes of getting away in John Badham’s

Saturday Night Fever, Michael Giacchino’s mournful limbo in J.J. Abram’s

Lost, or Gustavo Santaollala’s evocative lament for tragic cowboys in Ang Lee’s

Brokeback Mountain. Their music embody the films they are part of as a kind of emotional architecture. (Or if not “embody,” perhaps “underline”?) The quickest way to appreciate this is to watch a horror movie and have it unfold with one covering one’s ears. The result is strange: somehow, the scare is lesser, unless you are F.W. Murnau making

Nosferatu, and silence is not an impediment to a cinematic evocation of exquisite horror.

A great musical score is designed like an architecture of sound—each trill and melody composed to tease out something in us the moviegoer, and no one in Dumaguete knows this more than Ian Manuel Mercado.

Still a music student in the College of Performing and Visual Arts in Silliman University, Mr. Mercado has somehow found a way of gaining some traction in the international world of film composing—thanks, in large part, to the Internet. And more specifically, Soundcloud, a popular music-sharing social networking site.

“Someone from UNESCO wrote to me to ask if I was interested to work for a recent project,” Mr. Mercardo said. “It was a World Heritage and Cultural Diversity promotional video, and I was to work as a film scorer together with some other amateur composers picked from around the web. The rest, as they say, is history.”

That stint led him to obtain a full merit-based membership in the Society of Composers and Lyricists, or the SCL, where he was able to meet with fellow musicians—mostly composers—notably some legends like James Newton Howard, Bryan Tyler, Steve Jablonsky, Christopher Lenertz, Bill Brown, Deane Ogdene, and many more. “I met them in one of the SCL’s composers’ symposia where we I got the chance to further develop my skills in film scoring,” Mr. Mercado said. “The SCL is also where composers get the chance to get their scores laid on some short or big films, advertising campaign and alike.”

Mr. Mercado—a talented pianist and also a member of Silliman’s Campus Choristers and Ating Pamana—has always been into music composition, but scoring for films has of late become the major focus in his early blooming career as a musician. And in that regard, he has managed to delineate the subtleties demanded by this particular craft—something leavened by the challenge of cinema: “What is it that separates a composer from a film scorer? I believe it’s the ability to look at a movie, not just from a musical perspective, but from a filmmaker’s as well,” he mused once to me in consideration of what he does. “An effective score must have the same kind of exposition and development and recapitulation that an effective script has. And if you take out elements along the way, or leave out exposition, then it doesn’t work quite as well. Moreover, there are some more other crucial viewpoints in film scoring that we should consider. Geography, for example. I always look for the geography of the film I’m working on, because I’ve found that if I can attach some cultural sensibilities to it, it’s easier for me to find my way through musically.

“Then there is theme, and there is character. I’ve also discovered that directors habitually have notions of musical themes to characterize individuals in a picture, but I’ve never really understood that, and I’ve never worked that way—unless I was really forced to. While a number of situations might combine to cause a motif to recur in situations involving the appearance of a particular character, I’d maintain that in my scores, this never has a conscious genesis for me.

“There’s also orchestration and instrumentation. For me, less can really be more in film scoring. I feel that that’s why so many short films are so impressive musically. They are often scored with just a few instruments. Although this may be the result of budgetary restrictions, personally I find that kind of thing terribly appealing. As long as you can make an effective counterpoint out of a two- or three-player ensemble in a score, it would still be as grand as an 80-piece orchestral score.”

A lot of these you can see in his score titled

Redemptionem Inter Racúndiæ, something of a favorite of mine. I like its slow build-up, announced by some bells pealing, and then a hazy percussion blend that eases into a thrilling rhythm. There is narrative movement to the music—harp, flute, and string soon ebbing and flowing to the sound of waves crashing, reminiscent of Trevor Jones or James Horner or Randy Edelman. You close your eyes, and with the music alone, your mind lends itself to a movie of your own making. Such is the power of film scoring. As complement to film, it is the element that pushes the image to a higher resonance. On its own, it creates its own narrative gravity and propulsion.

Mr. Mercado has come into his own, of course, as a study of influences. “I’d point out Gustav Mahler and John Williams if I really have to name names here,” he said. But his artistry, it seems, has enough wellspring that come from some secret personal source. “A lot of my inventiveness comes not from direct research of the various genres or people. More from my own innate feeling for a style—from medieval to modern-day music,” he said. “It’s an impressionistic kind of thing.”

That personal impressionistic feel for sound seems to work for him. The doors are certainly opening for Mr. Mercado. It won’t be too surprising to find a future movie with his name indelibly impressed on the celluloid projection with “music by” attached firmly to it.

Labels: dumaguete, film, music, silliman

[0] This is Where You Bite the Sandwich

Saturday, May 05, 2012

11:30 AM |

You Die for Stories. They are Important in Our Lives.

11:30 AM |

You Die for Stories. They are Important in Our Lives.

“My cousin Helen, who is in her 90s now, was in the Warsaw ghetto during World War II. She and a bunch of the girls in the ghetto had to do sewing each day. And if you were found with a book, it was an automatic death penalty. She had gotten hold of a copy of ‘Gone With the Wind’, and she would take three or four hours out of her sleeping time each night to read. And then, during the hour or so when they were sewing the next day, she would tell them all the story. These girls were risking certain death for a story. And when she told me that story herself, it actually made what I do feel more important. Because giving people stories is not a luxury. It’s actually one of the things that you live and die for.”

“My cousin Helen, who is in her 90s now, was in the Warsaw ghetto during World War II. She and a bunch of the girls in the ghetto had to do sewing each day. And if you were found with a book, it was an automatic death penalty. She had gotten hold of a copy of ‘Gone With the Wind’, and she would take three or four hours out of her sleeping time each night to read. And then, during the hour or so when they were sewing the next day, she would tell them all the story. These girls were risking certain death for a story. And when she told me that story herself, it actually made what I do feel more important. Because giving people stories is not a luxury. It’s actually one of the things that you live and die for.”

~ Neil Gaiman

[Art: The Guardian Post by Razceljan Salvarita]Labels: photography, writers, writing

[0] This is Where You Bite the Sandwich

Friday, May 04, 2012

12:36 AM |

The Vintage Stylist

12:36 AM |

The Vintage Stylist

Part 6 of the Dumaguete Design Upstarts Series

No one argues with Coco Chanel. The legendary fashion designer once said: “Dress shabbily, and they remember the dress. Dress impeccably, and they remember the woman.”

This declaration defined, with the same stylish precision of a Chanel suit, the importance of dressing well. And perhaps, rallying to this call, the truly stylish among us—and not merely the unfortunate fashion victim—aim for that impeccability of dress.

Why? To make a mark, to forge an identity, to express who we are. Fashion becomes emblematic in this regard—and perhaps this is why a particular species of enterprising people have evolved to answer that need. You know who they are. The stylists.

Stylists, especially the best ones, are avid readers of fashion. They are the able conjurers of sartorial language, which marries personality with cut fabric. On television, we get Rachel Zoe—although one might make the argument she does not exactly typify the best of such strange occupation. So forget Rachel Zoe. There’s somebody in Dumaguete who does exactly the same thing as the reality TV fixture does, but with decidedly less mugging for the camera. And decidedly with more creativity. Her name is Veronica Valente-Vicuña, and one can say she has made a life and career over her uncanny sense of what works for you, fashion-wise.

“I have always enjoyed going to flea markets and

ukay-ukay, ever since college,” Rona told me. “Being a bargain hunter, I get a rush when I find pretty items which would cost triple or more if sold in department stores. Even if the clothing item would be too big for me, I would still get it because my thinking is, I could just have it altered down to my size.”

Stylist and designer Rona Valente-Vicuna

Eventually that nose for bargain and style led to a kind of fashionable hording. “Soon I had bags and bags full of dresses,” Rona remembered, “So I thought, why not sell some?”

She started toying with that idea of commercializing her sense of fashion in 2006, but it took her until February of 2007 to get things really going. She opened her online store

Veronica’s Closet, initially listing only just six choice items.

To her delighted surprise, the dresses sold out within hours. “That encouraged me more,” Rona said, “And soon, with a good client list growing, I had to make a weekly upload schedule to keep up with the customer demand.”

A few of summers ago, she found herself participating in a program for fashion designing in Cebu. “I learned quite a lot from some of Cebu’s top fashion designers,” she said. That summer program ended with a fashion show at the Waterfront, which featured the participants’ new designs, things they created for class.

This soon paved the way for better things. “Subsequently, I was invited by Anya Lim of Anthill Fabric Gallery in Cebu to display some items from my website,” Rona said. “She had been buying regularly from my site, and she wanted me to sell my re-made dresses in her fabric gallery. She encouraged me to come up with a line, where altered and reconstructed vintage dresses are showcased.” Rona chose the name

Re/Dress for the line, which meant, simply, “to re-do the dress.”

She explained the concept behind the project: “Some dresses may have beautiful fabrics, but the dress may not be worn again due to tiny rips, runs, and others. This is where I come in. I totally revamp the dress. Using what fabric can be salvaged from it, I then add new fabrics and restyle the old design.” Clearly, what had began as a hobby—transforming old dresses and making them different and more fashionably current—soon became one of her sources of income. “And relaxation, too,” Rona admitted.

What is the underlying philosophy of her work? “To provide unique dresses, which are extra-special because of the history behind it, them being vintage,” Rona said. “As a member of Anthill Fabric Gallery and Stylissimo Sessions of Cebu, I believe in thinking green. By using old materials, I can do my part in saving the environment.” This philosophy led her to become part of a fashion show in Cebu called

Greenology, where designers made dresses using

retaso and recyclable materials. “I used old neckties for the headpiece, as well as men’s blazers and pieces from an old computer keyboard,” she recalled with a smile.

But her sense of style is not without study. For Rona, her influences consist of the style icons of past, which include Audrey Hepburn. “It is because of her femininity and how she carried men’s inspired clothing,” Rona said. “Her style was never fussy. She kept it neat and clean. You can’t go wrong with that.” There is also 1960s model Twiggy, whose slender figure—being both boyish and also ultra-girlie—was an inspiration for great designers of the time. “She rocked the mod look!” Rona said. “I love mod. Floral and geometrical patterns make me happy as well as solid-colored dresses decorated with bows and ribbons, buttons and zippers!”

From such confessions, one readily sees that for Rona, the love of vintage and everything related to it is what defines her sense of style.

Take her first collection

Lavender Fields with Anthill Fabric Gallery, for example. The whole look of the series foregrounds her aesthetics, which is essentially a worship of a laid-back vibe, hippie luxe and classic vintage all at the same time. There are the flowy dresses in paisley or floral prints, dresses with gauzy or silk fabrics, dresses with billowy white peasant shirts complete with embroidery—a style that defines what for Rona is soft, fun and young. There is the dress with the printed bib and belt from a vintage 70’s blouse, to which she added a gaze faconne fabric, which is like chiffon but is a bit stretchable. “I also re-used the original buttons from the blouse,” Rona said. “This dress is BoHo-inspired.” There are more of the kind in her inventory.

Gesta Gamo models one of Rona's creations

And what does she hope the future can bring for her? “I’m taking things in stride,” she said. “For

Veronica’s Closet, I hope to have a name for myself in the local Internet market as the shop to go for vintage and vintage-inspired dresses. For

Re/Dress, I am currently laying out the beginnings of what will be my spring/summer collection. And maybe one fine day, I can get featured in Preview, my favorite magazine. I can dream right?”

Yes, Rona, you can. And fabulously, too.

Labels: design, dumaguete, fashion

[0] This is Where You Bite the Sandwich

GO TO OLDER POSTS

GO TO NEWER POSTS

11:13 PM |

The Romantic Pessimist

11:13 PM |

The Romantic Pessimist

5:07 AM |

The Visualist of Common Sense

5:07 AM |

The Visualist of Common Sense

3:29 AM |

The Three Virtuosos of the Photographic Eye

3:29 AM |

The Three Virtuosos of the Photographic Eye

12:46 AM |

The Designer of Film Sound

12:46 AM |

The Designer of Film Sound

11:30 AM |

You Die for Stories. They are Important in Our Lives.

11:30 AM |

You Die for Stories. They are Important in Our Lives.

12:36 AM |

The Vintage Stylist

12:36 AM |

The Vintage Stylist