Monday, August 27, 2012

4:54 PM |

Checking to See If I'm Still Alive

4:54 PM |

Checking to See If I'm Still Alive

Labels: life, photography

[0] This is Where You Bite the Sandwich

Sunday, August 26, 2012

4:42 PM |

How We Use Pain

4:42 PM |

How We Use Pain

This is how some of us love. In Northanger Abbey, Jane Austen wrote: “I have no notion of loving people by halves, it is not my nature. My attachments are always excessively strong.” Excessively strong. That makes sense to me. I know a visual artist who made installation art of everything his ex-boyfriend left him with -- clothes, books, pictures, letters, unopened condoms. Art as a chronicle, art as biography. All that heap of a shattered life, all that remembrance fodder for creation. Because how else to transcend pain except use it for art?Labels: art and culture, life, love, quotes, writers

[0] This is Where You Bite the Sandwich

3:25 PM |

Silliman is in the Heart

3:25 PM |

Silliman is in the Heart

There is a strange predilection among all alumni of Silliman University to think of something specific every time they are confronted with the question bearing the concept of “home.” Regardless of their primary roots—whether they are from Manila or Morocco, Davao or Dubai, Laguna or Los Angeles—whenever you ask them, “

Kanus-a man ka mo-pauli? (When are you coming home?),” they invariably know “home” means Dumaguete. I have always found this fascinating.

Then again, it is a strange thing, being a Sillimanian. It is even stranger to consider the loyalty the university seems to demand of us, without protest at our end: we give in to the demand wholeheartedly, like a lover returning to a familiar embrace. Thing is, one learns to love Dumaguete (and Silliman) like the place is second skin.

I asked around what this exactly means, and the following students and alumni tried to help define it. My question was, “What is that one, specific, and tangible thing you love about being a Sillimanian?”

The writer F. Jordan Carnice wrote: “Everyone seems to know everyone, regardless of age, course, or batch.” BPO honcho Ian Sobong Malayang stresses out what that means by saying it is about “the sense of kinship and instant connection that you feel when you meet perfect strangers somewhere on the other side of the world and you find out that they’re Sillimanians, too.”

Francis Salvador gives it a name: “I know it’s a bit of cliche, but it’s the Silliman Spirit. It surpasses both time and place. Wherever you go, whatever you do, you feel like you’ve known each other for so long. It brings warmth and an unknown feeling of belongingness. I’ve experienced it countless of times.”

Student Tommy Villegas continues: “Silliman has this culture where people from different backgrounds can just hangout—or

tambay—together. It doesn’t matter whether they’re rich, highly academic, a local or foreign student…. Everyone can be friends, add to that the fact that even

ang mga sosyal sa Silliman

kay mo-try

og mga tosinohan or other cheaper places to eat, just to have a good time with friends. Somehow I find it all amazing.”

My cousin from Australia, Louella Moncal-Pineda, weighs in: “I love the amphitheatre, the dorms where I once stayed whilst there, the cafeteria, the T-rooms—now gone, I suppose, the Silliman Church. Also the friends, the classmates, the colleagues I once knew. My diploma, and of course my husband whom I met in Silliman. All these gave me the right to be called a Sillimanian and I take pride in that. Outside of these tangible stuff, it is the spirit that no matter who you have become and no matter where you are, make us stand equal with fellow Sillimanians.”

Emmanuel Fiel Dela Cruz thinks hard about it: “Maybe I’m not that rich or famous. Maybe I’m not the handsomest guy in the crowd—but I’m a

Sillimanian. The coolest term I know.”

That Silliman Spirit, for Mae Anne Yee, can translate to something useful in the real world: “One specific and tangible thing I love about being a Sillimanian is my diploma. I remember how wonderful the feeling was, when I was still applying for jobs, and I held out my diploma—and when they see ‘Silliman University’ on it, they give you that grin of admiration and say, ‘So you are a Sillimanian, huh?’ Wonderful!’ I always got hired.”

For Guam-based marine biologist Laurie Raymundo, that whole thing is the sense of being part of a community. From Hong Kong, writer Heda Bayron writes: “It’s the lasting personal connections. I spent only four years in Silliman. I don’t see my high school batch mates often, but when we do, it’s like we just pick up where we left. It’s amazing. You just belong.” Marvin Luther Tan agrees: “I love the fellowship with Sillimanians as you meet them anywhere.

Bisan first time pa mo nagka-meet, you can share lots of common things.”

Perhaps that sense of community is shaped for the most part by the environment in campus, and Zara Dy muses: “I guess it has something to do with the rich history that permeates through the Silliman air that we breathe on campus. It could be illustrious, notorious, undocumented, forgotten (to all but one)—the magic lies in the fact that anyone who has spent time in the campus can claim such history because, not only does Silliman willingly indulge the searcher with great stories, the environment allows you to weave beautiful ones of your own. Silliman becomes, not just a school, it’s a lifestyle.”

Lifestyle. Being a Sillimanian is a kind of culture—and often that translates to the magnificence of the arts and culture scene on campus. The whole thing, for Paula Bastareche, is a careful balance of culture, academic excellence—and decadence par excellence.

For student and bike enthusiast Emmanuel Rotea Tecson, that means “the countless activities—talks, plays, and other performances, often open and free to the public!” For photographer Darrell Bryan Rosales from Bohol, that means “a chance to perform at the prestigious Claire Isabel Luce Auditorium.” For actor Earnest Hope Tinambacan, it is “the freedom to wear slippers and shorts—and the colorful cultural life.” For Giselle Iris Alano, it is “the freedom that allows us to be whoever we want to be: artists, free-thinkers, bohemians, drunks. Silliman is a breeding ground for cool people because here, we let people

be.”

For ABS-CBN regional news anchor Primy Joy Cane, what she loved were the season passes to all the cultural shows. “Man, I wish I could turn back time and attend every show at the Luce. Looking at students from other universities makes me realize how culture-starved most of them are. The infusion of theater, dance and song into a Sillimanian’s university life is what makes us whole.

Makasabay sa hinubog nga inom, pero kabalo gihapon mo-appreciate sa music nila Jay Cayuca, Michael Dadap... I miss that so much.”

Divah David-Sabordo sums it up: “Being a Sillimanian makes me feel not any less nor any better than anyone else. The whole experience reminds me to always walk with my feet on the ground but my head in the clouds. Looking back when my parents chose Silliman for me, they could not have any better choice. And I couldn’t be more thankful.” And Jascer Merced agrees: “When I walk around the campus or drive around on my motorcycle everything seems to slow down. There’s something about Silliman that makes you pause for a while and just hear the trees sway.”

I want to end with what songwriter Anna Katrina Espino has to say about what she loves about being a Sillimanian. “The acacia trees. No joke. Walking around the campus at four or five p.m., this gives you that feeling of serenity.

Like you’re exactly where you’re supposed to be.”

Exactly.

Labels: dumaguete, life, silliman

[0] This is Where You Bite the Sandwich

Sunday, August 19, 2012

3:32 PM |

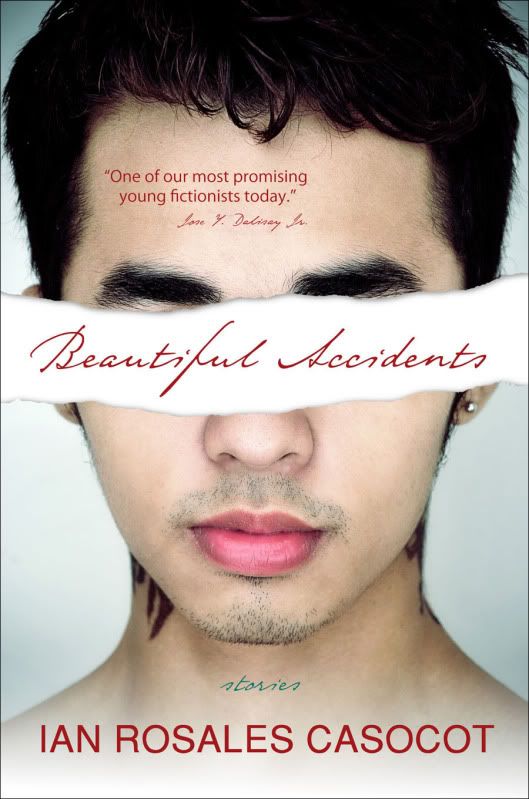

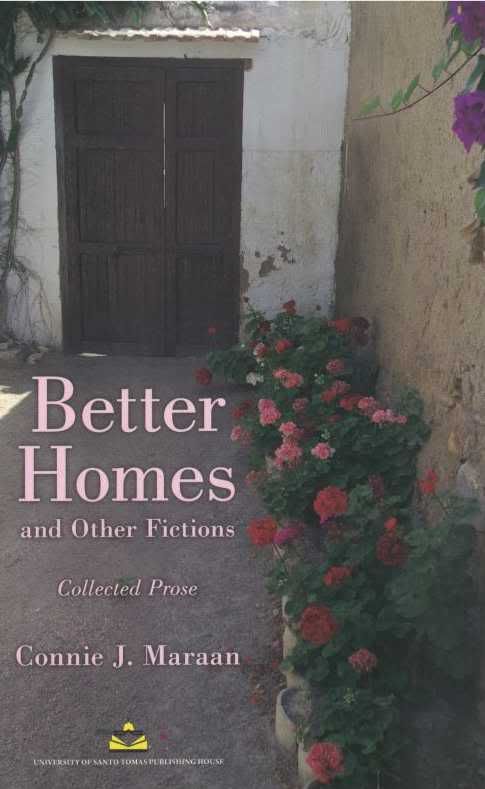

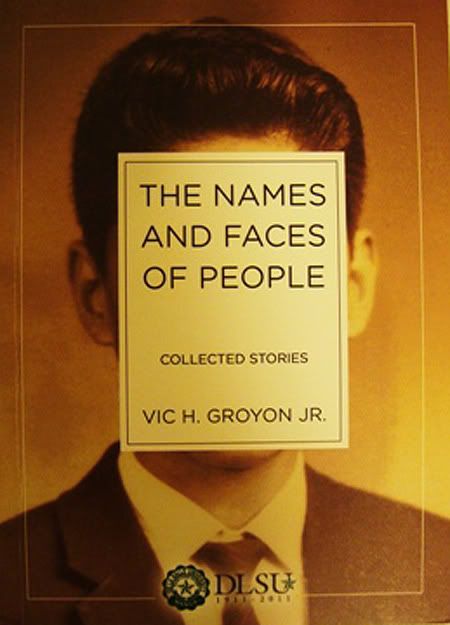

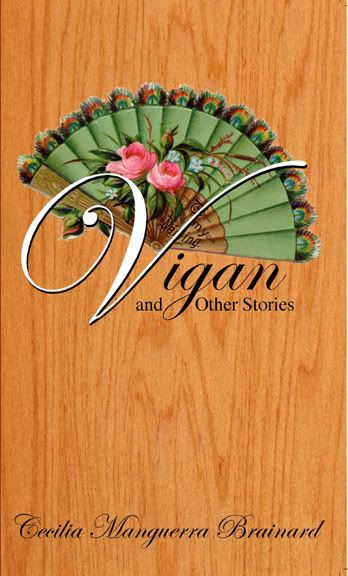

The Fiction in English Finalists for the 31st National Book Award for the Novel and for the Short Story

3:32 PM |

The Fiction in English Finalists for the 31st National Book Award for the Novel and for the Short Story

The Manila Critics Circle and the Nartional Book Development Board just announced the finalists for the 31st National Book Award. The above are the fiction in English finalists for the shorty story collection and the novel. Get the rest of the finalists

here.

Labels: awards, books, philippine literature, writers, writing

[1] This is Where You Bite the Sandwich

Friday, August 17, 2012

9:49 AM |

Some of What I’ve Learned

9:49 AM |

Some of What I’ve Learned

In the tradition of recent years, I would have said, “Today is the ninth anniversary of my 28th birthday.” But no more. I’m 37 years old as of this writing, plain and simple. There’s a good life behind that awesome number—especially coming from somebody who once dramatically thought he wouldn’t live past his 33rd birthday. Each day thereafter has always felt like an extension of a blessing, even taking note of all the hardships and the heartbreaks.

Edging past the mid-thirties is perhaps a time fraught with some of the most dramatic changes in a life—all of them internal, all of them requiring a bemused, if slightly alarmed, change of perspectives nobody really warns you about.

Because you still have some vivid memories of being very young and all that it entails: the casual if misplaced feeling of a limitless future; the late nights spent in pursuit of hedonistic bliss; the energy that seems incapable of running out. But what you soon learn is this: you’re young, and suddenly you’re not so young anymore. Forty is suddenly not too far away.

But you learn to live with that acknowledgment, the way you learn to accommodate your autobiography of mistakes. You learn to pace yourself as your body slowly betrays you, often in subtler ways than you can imagine. You learn to deal with broken dreams and too many compromises. You learn to harden up just a bit more into the realization that you can’t really please everybody. You learn there’s a sudden finiteness to the future, and you must indeed plan for it. You learn that you really are your parents’ child, after all, after years and years of denial and rebellion.

You also learn to accept, with some bewilderment, that you have become The Man. Somehow now a part of the “establishment”—that shadowy distinction in the adult world which the very young instinctively flails against. Ten years ago, for example, I edited an anthology titled

FutureShock Prose: An Anthology of Young Writers and New Literatures, with all the conceit of generational writing (and anthologizing). I made a young man’s claim that this was “us,” that this was “now”—that we were a generation of writers markedly different from those that came before. And perhaps that was so. We were

the “young writers.” We were, in the borrowed words straight from Alvin Toffler and modified by Cesar Ruiz Aquino, “future shock.”

But last year, also during my birthday, Carljoe Javier—who comes from my generation of writers—came all the way from Manila to help with the launch of my books

Beautiful Accidents and

Heartbreak & Magic in Dumaguete. In the middle of a bite of pizza in Hayahay, he confessed to me this astonishment: “I was with some younger writers the other day, Ian—and it suddenly occurred to me that to them, we were already old fogeys. And there I was still thinking, ‘I am a young writer!’” Apparently, we no longer are. None of us know when that happened, or when the tectonic plates shifted—but we were the new establishment.

Ouch.

But you learn to live with that.

What I’ve learned the most, however, is the appreciation of my own mistakes. In many ways, my mistakes make more sense to me than my triumphs because they seem to be the very molders of character. I am, shall we say this then, the fruit of my mistakes, and what I’ve accomplished thus far seem very much only the icing of lessons learned from them.

The Japanese have a way of putting this metaphor for life in their art. They call the process of mending broken things—broken vases, broken cups, broken teapots—with gold molding “kintsugi.” As the artist Barbara Bloom once described it: “…They aggrandize the damage by filling the cracks with gold, because they believe that when something’s suffered damage and has a history it becomes more beautiful.”

Makes sense to me.

This way, my heart—and my life—is all history and glitter. And I like the very idea of that.

Labels: life, love

[1] This is Where You Bite the Sandwich

Sunday, August 05, 2012

10:07 PM |

The Architect of Dreams

10:07 PM |

The Architect of Dreams

Part 10 of the Dumaguete Design Upstarts Series

The first time I met Ray Villanueva, he was part of a singing group of brothers performing at the Luce Auditorium. This was many years ago, most details have been forgotten, and I didn’t really know him. The second time I met him, it was at Gabby’s Bistro and he was with his lovely American wife Amy. They were a vision on bicycles, and upon inquiry, I was told that they were in Dumaguete City “to try to give something back to the country.” One learns to instantly adore people with such dreams. It is such a rarity, especially for a country with rabid immigration dreams.

I wouldn’t remember anything about the singing past until last Christmas when, around the sumptuous holiday banquet prepared by our host Arlene Delloso-Uypitching, Ray played the piano “for his supper”—a superb rendition of “Claire de Lune”—and we were quickly told by Moses Atega of his musical past. “Now I remember you,” I told him. The answer I got was a sheepish smile.

But this article is not about his singing, nor his piano-playing, nor his sheepish smile. This will be about Mr. Villanueva as an architect, and his vision for building, with a thrust for community and sustainability. Let’s call it “developmental architecture.”

“My calling to architecture started while I was in George Washington University,” he told me. “I was taking up pre-med studies then. And one of the general education requirements was an art class. I have always loved drawing, but did not have the opportunity to take a drawing class before. I fell in love with it. From then on, I decided that being creative would be a part of my life.”

That decision led him to the University of Maryland to pursue architecture. While in the program, he was exposed to a Beaux Arts-rooted program and learned from distinguished professors—and soon he graduated with the second highest GPA in class. Ray would soon continue on to the University of Washington in Seattle, to focus on sustainable architecture. For his degree, he presented a thesis he titled “Architecture for People Who Need It”—which provided the blueprint for how he wanted his architecture to be about: as a model for sustainable development in developing nations.

Among his works that best define that aesthetics are Yakama Design-Build at the University of Washington and the Neighborcare Health Rainier Beach Medical and Dental Clinic.

And now, he’s here in Dumaguete as part of Foundation University’s architecture program. What does he hope to achieve with his work in the coming years?

“In the short term, starting with the current school year at Foundation, I am trying to help establish the first Design+Build Program in the Philippines called Estudio Damgo,” he said. “This is similar to the program I participated in at the University of Washington where the students will be responsible for the design and construction of a structure in the local community. The project will involve community-based design in the form of a series of open forum community meetings and students will be in charge of everything—from design, construction drawings, and materials research, to the actual swinging of hammers, pouring of concrete, and installing fixtures.”

Estudio Damgo, according to Rey, will be a “learn-by-doing” program that will provide lessons that will last well beyond the classroom and will increase the students’ marketability post-graduation. “In the process,” Ray continued, “the local community gains a structure that showcases cultural relevance and innovation, while serving as an example that design and Architecture can make a positive impact by creating places everybody can enjoy.”

Somehow, all this is part of a dynamic life plan. “I am excited at the chance to work with the students and faculty to cultivate new ideas in architecture,” Ray muses. “And also to discover more about my heritage, and to pass on my experiences in design-build, construction, and community service. I feel that I have the potential to make a positive impact in local Filipino communities.”

Truly, Ray may have been born in Wheeling, West Virginia, to parents Dr. Romulo and Kathy Villanueva. His heart, however, has always been connected to his place of roots—Dumaguete. (His father is an Outstanding Sillimanian Awardee recognized for his medical mission work in the Philippines and abroad.) “My parents are my biggest influence,” Ray said, “Despite my upbringing in the U.S., they were clear about exposing my brothers and I to Filipino culture. Being in Dumaguete and the Philippines for the past months, I’ve discovered so much about my parents and myself. I am much more Filipino than I thought I was.”

For Ray, one of the greatest lessons his parents have imparted to him and his brothers was the “responsibility to give back.” Which is why he has come back to the Philippines, with Amy. “The importance of service—to the environment, to one another, to country—has always been a part of my life,” he said. “Service has led me to unique experiences like volunteering in National Parks, helping in medical missions in the Philippines and Peru, and reaching out to victims of natural disasters like Hurricane Katrina. The lessons I’ve learned from these volunteer opportunities formed central ideas of my graduate school thesis project based in Mindanao, and led me to work for Miller Hayashi Architects in Seattle to experience community involvement in design. This was ultimately the reason why my wife and I decided to quit our jobs in the U.S. and come to the Philippines.”

That’s one man going against the flow. Here’s to Ray, and may there be more people like him, especially from among us.

Labels: activism, architecture, art and culture, dumaguete, people

[1] This is Where You Bite the Sandwich

GO TO OLDER POSTS

GO TO NEWER POSTS

4:54 PM |

Checking to See If I'm Still Alive

4:54 PM |

Checking to See If I'm Still Alive

4:42 PM |

How We Use Pain

4:42 PM |

How We Use Pain

3:25 PM |

Silliman is in the Heart

3:25 PM |

Silliman is in the Heart

3:32 PM |

The Fiction in English Finalists for the 31st National Book Award for the Novel and for the Short Story

3:32 PM |

The Fiction in English Finalists for the 31st National Book Award for the Novel and for the Short Story

9:49 AM |

Some of What I’ve Learned

9:49 AM |

Some of What I’ve Learned

10:07 PM |

The Architect of Dreams

10:07 PM |

The Architect of Dreams