Friday, October 31, 2014

8:12 PM |

The Dead in Riverdale

8:12 PM |

The Dead in Riverdale

Like with many staples of childhood, the love for

Archie Comics is something I think of fondly when I do remember it, but know that it is an artifact from more innocent days you don't really mourn for when you learn to let go. Sure, all those double digests were fun digressions in a teenager's life, and sure, we did learn to somehow sketch out with the ease of over-familiarity the outlines of Archie's orange top (with those strange hashtags for sideburns), Betty's blonde ponytail, Veronica's brunette mane, and Judghead's iconic crown (cap?). But when we let go, we let go. We only returned, once in a while, when we were trapped in some waiting room at the dentist's, and the only reading material handy was a well-worn squarish issue of

Archie. In those occasions, we dipped into the old pleasures, often chuckling to ourselves what made us think these storylines were funny. I think the publishers know this, and so it has tried in recent years to put some edge into Archie. They have taken our beloved characters from Riverdale and make them go through some new spin. And the latest is

Afterlife with Archie, wherein Hot Dog dies in the very first page, then Sabrina brings him back to life for the heartbroken Jughead -- and unwittingly unleashes a curse where bringing back the dead truly meant that: the undead in Riverdale, in the form of zombies. I heard about this series early this year, but never felt compelled to check it out. Because, like I said, relic from childhood you abandon without much guilt. But for some reason, this week, I found myself reading the first six issues, which completes the first arc of the story, and leads us to the second one that begins with Sabrina in limbo. And yet the first arc was delightful enough, if only to see many of our favorite characters -- Jughead, Ethel, Moose, Midge, Mrs. Grundy, Prof. Weatherbee, Coach Clayton, etc. -- turn to ravenous living dead, devouring everyone during a Halloween dance. But what I liked the best was the scrubbing of humor: this is a serious comics story, almost rivaling the dread of

The Walking Dead, although we have yet to turn to the part where the living would prove to be more monstrous than the dead. And the flashbacks, and the back stories, and the first-person narratives from such unlikely sources like Smithers. Archie Comics has grown up, and does it so via a horror trope we least expect it to embrace. It's perfect Halloween reading, and has much to do with teenage nostalgia, and pricking that nostalgia, and welcoming it with perverse delight.

Labels: books, comics, halloween, life

[0] This is Where You Bite the Sandwich

Thursday, October 30, 2014

7:42 PM |

Horror Hits and Misses

7:42 PM |

Horror Hits and Misses

I get asked this all the time:

What are my favorite horror movies? I don't know how to answer, because I hate such questions, and because my choices are pretty personal -- all marked by a certain appeal that speaks only to me. I think of Todd Haynes'

Safe (1995) as a very effective horror movie, for example, but for most people it won't be. There are no monsters in it, after all. And if there is one, it is the mind of our protagonist/victim. And yet nothing is more horrific to me than a bewildering affliction of the mind -- I think of Roman Polanski's

Repulsion (1965), which I first saw as a 21-year-old living in an alienating city like Tokyo. And so I saw that movie as more than just careful, frightening study of the descent into madness; I saw it as a depraved, gothic articulation for alienation, a kind of warning for my own existence then. Julianne Moore's Carol White in

Safe, a prototypical suburban housewife who's starting to feel allergic to the world around her, has so much in common with Catherine Deneuve's Carol (

coincidence in names?) in

Repulsion, a beautiful but repressed French beautician living in London who's starting to mentally crack from what she perceives to be horrific advances by men who hound her. Polanski's film vocabulary fleshes out the horror elements more than Haynes does, but they're effectively the same movie. Horror is often mistaken for its tropes, which becomes problematic when you consider Arthur Penn's

The Miracle Worker (1962), which basically tells the otherwise heartwarming story of how Helen Keller gets saved from crippling blindness by her tutor Anne Sullivan -- but Penn films the story like a horror movie. It

feels and

looks like a horror movie, but it's not.

Which is why I hate answering the question above. I get defensive, and I become long-winded in my explanation of choices.

But every year, around Halloween, I do take time to almost exclusively watch horror films, taking note of the cult status and the iconic contribution each title has given the horror genre. In other words, I ransack the whole horror canon, an ongoing project that I doubt will ever end.

Last year, I started with six horror classics in black and white that have eluded me for so long. When I finally saw Jack Clayton’s

The Innocents (1961), what I couldn’t believe was how I’d missed out on this film in all those years. It being a Deborah Kerr starrer should have already recommended it, but I took my time getting to this film. It turned out that I loved it, so much so that a year later, I still remember its haunting set pieces, its incredible atmosphere. It is a taut, psychological thriller based on Henry James’

The Turn of the Screw, where we don’t exactly know the boundaries between sanity and madness, the ghosts and the living, the victim and the victimizer. It is, without doubt, a great horror film.

Then there was Lewis Allen’s

The Uninvited (1944). Its iconic for being the first film to take the haunted house genre very seriously, and not played for laughs or ridicule as was the practice before this. (Think of Scooby-Doo unmasking the human culprit behind the horror — that’s how it was usually played.) It won't play well for those seeking out a bloodcurling tale, and certainly not for a crowd inured by the torture porn of such films as

Hostel or

Funny Games or

A Serbian Film. Its horror is more subtle, which I admired, and in consideration of its place in horror film history, it proved quite educational, like you were seeing the genesis of a genre being played out in front of you, one trope being invented after another.

Jacques Tourneur’

Cat People (1942), on the other hand, does a good job of dramatizing, in tantalizing black and white shadows, what everyone who has had their heart broken has been through: rage, jealousy, lust. And the feeling of having a dark monster within us that threatens to come out because of those provocations. Here, Simone Simon’s cursed woman marries a man who loves her unquestionably, but she begs off from more intimate contact, because even a kiss will unleash some ancient evil in her. She turns into a predatory cat, and she can devour. But it’s not just lust that can consume her and make her transform — jealousy, too, and rage. She is, in a sense the grandmother of both Edward Cullen and Jacob Black. (

Hahaha.) I love this film. I love the perfectly staged fright pieces that involve nothing more but shadows, sound, and the darkness of our imagination.

And sometimes, there's poetry in a horror movie. There is no denying the sheer poetry of Tourneur’s other horror classic,

I Walked with a Zombie (1943), which is a film scintillating with lines written by Inez Wallace, Curt Siodmak, and Ardel Wray — things like: “Everything good dies here … even the stars." I have a soft heart for this movie, about a good-hearted nurse who loves her married boss so much, she tries everything to cure his ill wife, the titular zombie. But a horror movie this is not. It’s a love story every which way. It’s a romanticized tale of life in the tropics, voodoo and all. Heck, even the zombie in this movie walks about in flowing gowns.

There was also Tod Browning’s

Freaks (1932), a curious film peopled by circus people of various sorts of deformities (the bearded lady, the Siamese twins, the dwarf, and so on and so forth…). But the one that’s crucial to the story’s tension — an evil deformity of the soul — is embodied in the film’s central villain: a beautiful, very normal-looking, but wily trapeze artist who uses her charms to seduce the circus’ dwarf who just happened to come into a great fortune. The film has been touted as an influential horror movie, a pre-Code artifact that has more in relation to German Expressionism that anything else. True enough, the assault in the end is chilling — but we are incredibly on the side of the freaks. In the end, there’s nothing horrific about this film. It’s a warm and fuzzy love story.

I now understand perfectly the cult status attained by Herk Harvey’s

Carnival of Souls (1962), which has reportedly influenced the aesthetics of David Lynch and George A. Romero. It’s quite an effective independent horror film, even counting the obvious ticks brought about by its low budget. (Then again, the low budget was what made many horror films — particularly Sam Raimi’s original

Evil Dead (1981) or Francis Ford Coppola’s

Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1992) — effective. There’s something about the enterprising crudeness of the filmmaking that adds to the sense of the horrifying.) Even then, the pacing of its story — about the sole female survivor of a car crashing into a river, now suddenly being haunted by a pale-faced ghoul — keeps the tension tight, and the final reveal is worth it. I love how this predates the ghostly dimension of Christopher Gans’ atmospheric

Silent Hill (2006). And that visceral organ score! A chiller to the bone.

And then there are the more contemporary ones, and even some of them defy our expectations of a horror movie. Take Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger’s

Black Narcissus (1947). This gorgeously shot, intricately mannered drama about five nuns battling temptation and altitude sickness in 1940s Himalayas is only a

kind of horror story: Deborah Kerr’s uptight and emotionally broken Sister Clodagh is the central character, but the growing malevolence focuses on Kathleen Byron’s Sister Ruth, a psychologically disturbed woman pushed to the edge (

hahaha, I made a pun) by carnal desires. The above shot of her is the most chilling image from the movie. It took me a while to get to this film, but now that I have, I can very well understand Martin Scorsese’s fascination over Michael Powell. I loved

The Red Shoes and

Peeping Tom — and

Black Narcissus just cemented for me Powell’s genius.

Then there is Masaki Kobayashi’s

Kwaidan (1964), for example. It is a visual feast above all. An anthology of traditional Japanese ghost stories, the film disregards conventional narrative for the most part (the last unfinished segment is a prime example) but never shies away from its attempts to seduce our senses while terrifying us with that kind of dread and unease only Japanese cinema can do: a face reflected on the liquid inside a teacup, or the slightly open smile of a wintry ghost to reveal a sinister

ohaguro (blackened teeth) inside. This is not Wes Craven or Shirley Jackson territory of horror. It is of the sublimated kind many might even find tedious. But the pace is made more unworldly by set pieces that borders with the surreal. Once you allow yourself to succumb to its tentacles, however, it will render you breathless.

And then there is Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s

Kairo (

Pulse, 2001), which I watched because it landed on

Time Out London's list of 100 Best Horror Films of All Time, a comprehensive enough list that had me admiring the thoroughness of the editorial choices. It beat out so many other titles from the huge pantheon of Asian horror that was churned with so much horrific regularity in the last decade. But watching it only underscored for me how so many of those films — and there were a lot of good ones — really were just run-of-the-mill productions that tried to make dreadful presences of everything in our ordinary lives, from cellphones to acacia trees to dating. In Pulse’s case, it’s the entire Internet, and how our online lives make ghosts of us all. It makes a good point — heck, the online world is full of zombies whose lives are all Facebooked and Twittered and Instagrammed and so on and so forth — but the years have not been kind to this kind of movies. They’re suddenly so silly now, and

Pulse above all.

Haynes’

Safe (1995) is a horror movie of a completely different sort: the monster is the world, especially if you suddenly develop an allergy towards it. The film calls it “environmental illness,” and I know how that feels like. I saw this film way back in my cinephiliac college days, and it scared the hell out of me then — the slow descent to allergy hell of Julianne Moore’s pampered housewife, the slow buzzing score that underscores the dread, the insight into a world overrun by toxins… It gets didactic, at times — especially in the last act set in a desert retreat, but everything feels real. The horror becomes the realization that this could happen to you.

And finally, there is the story of the tragic prom girl turned fire-starter, a horror classic I turn to once in a few years. What I love about Brian de Palma’s adaptation of Stephen King’s first novel,

Carrie (1976), is how the movie’s titular monster is not the evil presence in the story at all. It’s other people, the so-called “normal” ones. They’re the ones who are truly monstrous. Which is of course a horror movie staple. Take a look at James Whale’s

Frankenstein (1931), or Browning’s Freaks, or just about any of King’s greatest tomes, like

The Shining. It’s ordinary people we should be most scared of. I revisited this classic last year before I set out to watch the critically-reviled remake by Kimberly Peirce. And the horror has not lessened over the years — although I’ve observed that the telekinesis, strangely enough, doesn’t really figure so well in the film, save for the moving of ashtrays, the bursting of lightbulbs, and the bumping of kids in bikes. Until the massacre at the gym, of course. The central horror lies in the figure of the evangelical mom, whose godly pronouncements still send chills down my spine.

Labels: film, halloween

[0] This is Where You Bite the Sandwich

Saturday, October 25, 2014

4:10 PM |

Notes on a Short Story: The Flicker

4:10 PM |

Notes on a Short Story: The Flicker

I wrote "The Flicker" because I wanted to scare myself. Before this, I had written one other story -- "The Painted Lady" -- when I was still studying in Japan, which tried to limn the atmosphere of a horror story, but its eventual effect laid bare the true nature of its intentions: I had written it as a kind of commentary about the exit of an old flame. It was my heartbreak disguised as a vampire story. I think it succeeded more or less as an emo take on lost love, skirting much of the vampire lore and the horror tropes and treating the genre wholly as some vague metaphor to what I was feeling inside: betrayed, lost, in mourning, still hopelessly pining.

"The Flicker" was none of that. I set out to write a horror story, and I wanted to horrify myself as best as I could.

In preparation for this,

I read. I always read before starting a story, to soak up on the cadence, narrative structure, and effect that other writers have accomplished with similar projects so that I, too, could be able to at least kindle a bit of inspiration to start things off. I read a bit of Stephen King's

On Writing, his memoir of the craft. In it, he demonstrated some of the things he was talking about writing in his book, and these demonstrations eventually became a short story he titled "1408." It was a haunted hotel room story. The excerpts from the book weren't complete, so I sought out the entire story and read it in one go -- and it proved to be one of the scariest things I had ever read.

I wanted to carry over some of those feelings of dread into the story I wanted to write. I wanted to write about a haunted house in a Dumaguete subdivision. I wanted to have a twist in the end that was adequately surprising, but also inevitable. I wanted to have turns in the plot that would push the reader to expect something -- like the typical "jump scare" in a horror movie -- only to thwart their expectations. And THEN to plunge them into something totally unexpected soon right after. I remembered that old Charlie Chaplin story about being asked by the screenwriter Charles MacArthur what made something funny in a movie, say involving a woman and a bananan peel.

How do you make that funny and fresh on film? Mr. MacArthur asked Mr. Chaplin. The great man of silent comedy said that he'd show a shot of the banana peel on the street, then a shot of the woman walking towards it, then a shot of the woman seeing the banana peel, then a shot of the woman walking around it, then a shot of the woman walking away, looking self-satisfied with her caution -- and then a shot of the woman falling promptly into an open manhole.

All that, and also I really wanted to see whether I could accomplish a haunted house story -- that most hoary of all hoary horror tropes -- and get away with it without making it predictable.

I think I accomplished what I set out to do. I promised myself I would not work out an ending before even penning the story. I wanted the ending to come to me organically, whatever that meant. I still remember the night I came to the ending. While I was writing it, in the process horrifying myself with the ending I managed to come up with, I felt the hair at the back of my neck stand, and I could feel some spectre -- a ghost? a ghoul? -- standing behind me while I pounded out the last few words of the story. That image of knives and flesh and bone crept me out, and I swore right then and there I would never write a horror story again.

I wrote this story at the tail-end of 2007, a surprising year. It was surprising because I became quite prolific that year, some happy accident of circumstance, drive, and inspiration. I wrote a lot that year, and came up with a sizeable inventory of short stories slated for publication. Before that, I used to complete at the most two stories a year, and I was also just coming off a long period of writer's block, which lasted three years or so, and which I thought would proved to be permanently crippling -- I had no idea it was slowly tapering away. I wrote about eight stories that year. It was a magical year.

"The Flicker" was first published in Philippines Free Press

, 22 September 2007. It was later published in Philippine Speculative Fiction 3

, edited by Dean Francis Alfar and Nikki Alfar (Kestrel, 2007). Later, it was anthologized in The Best of Philippine Speculative Fiction

, edited by Dean Francis Alfar and Nikki Alfar (University of the Philippines Press, 2013). It is also included in Heartbreak and Magic: Stories of Fantasy and Horror

(Anvil Publishing, 2011).

Illustration for the story by Hersley-Ven Casero, also published in Heartbreak and Magic.Labels: fiction, horror, life, writing

[0] This is Where You Bite the Sandwich

Friday, October 24, 2014

6:13 PM |

Life is Lots and Lots of Bath Oils: An Appreciation of Nora Ephron

6:13 PM |

Life is Lots and Lots of Bath Oils: An Appreciation of Nora Ephron

I have loved Nora Ephron forever, and when she died in 2012, it felt so much like a personal loss. In the days after the announcement of her passing on from leukaemia, I read and read endless editorials and fawning obituaries about her and her legacy, as if to read all these was to somehow entice her spirit back to beguile us once more with her unique voice. I YouTubed her AFI tribute to Meryl Streep (

see below), and I was gobsmocked once more with the personality her wit took on. And then I went on a minor film bender, watching most of my favourite Ephron movies from

When Harry Met Sally... (which she wrote) to

Julie and Julia (which she directed).

I guess this often happens with the artists we admire and love. Our sometimes obsessive familiarity with their work signals for us some embracing illusion of connection, as if our devotion has permitted us some access to their personality, to their life, to their world. Woody Allen is one to vehemently deny autobiographical connection to his work -- "That's not me!" he'd always say -- but I've always considered that as a necessary caveat to the darkness he dramatises, often repetitiously, in his films. (

Oh, come on, Woody, I'd say,

at least some of these is you.) But not Nora Ephron. She mines her life and puts them out as fascinating tidbits in the films she has written or directed. And in the books that she has authored, we get a virtual confessional. She had done so in

Wallflower at the Orgy, effectively becoming one of popular culture's most effective wit. She was funny, and the way she saw her own life with bemused consideration proved so effective that her essays take on the sheen of the universal. She goes, "Whoa is me!" -- but follows that with an amused "Ha!" And that stance allowed many of us to laugh, and see parts of our own lives reflected in her assessment of hers.

It took me a while to get to

I Feel Bad About My Neck, her last volume of personal essays before she died. Ostensibly a collection of her own reflections on a New York woman's life at a certain age, it is instead some kind of valedictory. True, we do get the promised womanly reflections of womanly concerns -- the title essay, for example -- that has a lot to do with ageing and "maintenance." But at the end of the book, the remaining essays turn somber, if brightened by wryness and humour. The book becomes a contemplation of death. The turn starts with "The Story of My Life in 3,500 Words or Less," which has the undertone of the desperately autobiographical, bordering on the philosophical "What did it all mean?" In the end, the secret of life she gleaned is this: "We can't do everything." With the minimalist "What I Wish I'd Known," we get a human being's struggle to understand it all, even if everything cannot be done, and what is distilled are tiny moments of epiphanies from life. All of them recollected as scintillating insights, even if they spring from moments of utter banality. By the time we get to "Considering the Alternative," we are prepared for the book's very thorough reflection on death and passing on. She considers the matter of regret, and calls the entire thing a matter of

je regrette beaucoup: "Oh, how I regret not having worn a bikini for the entire year I was twenty-six. If anyone young is reading this, go right this minute, put on a bikini, and don't take it off until you're thirty-four."

Later, she writes: "I am dancing around the D word, but I don't mean to be coy. When you cross into your sixties, your odds of dying -- or of merely getting horribly sick on the way to dying -- spike. Death is a sniper. It strikes people you love, people you like, people you know, it's everywhere. You could be next. But then you turn out not to be. But then again you could be. Meanwhile, your friends die, and you're left not just bereft, not just grieving, not just guilty, but utterly helpless. There is nothing you can do. Everyone dies."

And then she makes us laugh, not to undermine the seriousness of her considerations, but to underline some more perhaps the only answer there is: to always enjoy the moment when you are most alive, because. "I need more bath oil," she ends her essay. "And that reminds me to say something about bath oil. I use this bath oil I happen to love. It's called Dr. Hauschka's lemon bath. It costs about twenty dollars a bottle, which is enough for about two week of baths if you follow the instructions. The instructions say one capful per bath. But a capful gets you nowhere. A capful is not enough. I have known this for a long time. But if the events of the last few years have taught me anything, it's that I'm going to feel like an idiot if I die tomorrow and I skimped on bath oil today. So I use quite a lot of bath oil. More than you could ever imagine. After I take a bath, my bathtub is as dangerous as an oil slick. But thanks to the bath oil, I'm as smooth as silk."

That's all of life, we learn. Not to skimp on bath oils.

Labels: books, film, life, people

[0] This is Where You Bite the Sandwich

Wednesday, October 22, 2014

12:02 AM |

The Color of Living

12:02 AM |

The Color of Living

I had no plans whatsoever in watching Jorge Gutierrez's

The Book of Life (2014), the new animated film produced by Guillermo del Toro. The trailers made it look like the film equivalent of a sugar rush -- all that colour, all that schmaltz, all that zaniness. The trailers gave me one big headache, and so when the film parked itself in the local cinema, I merely shrugged. But someone I knew wanted to watch it with me, and I'm not one to decline a movie invitation. I like going to the movies, and I was sure the film wouldn't be

that bad. When the screening was over, I found it wasn't bad at all. It was actually good. It was very, very good. True, the screen vomited with an avalanche of colours, and yes there was an abundance of zaniness. But it was all hyperkinetic colourful madness that somehow felt well-designed, intentional, organic. I think that turn-around for me is due mostly to the superb direction. Mr. Gutierrez knows how to tell a story, and in fact draws you in by dramatising that ability. The film opens with a bunch of rowdy students being bussed in to experience a day at the museum. But some intrepid lady tour guide takes them to a different adventure instead, showing them a closed-off exhibit about Mexico's Day of the Dead, and then regaling them with a story told from a book she called "The Book of Life." And in one tale, she unfurls the story of La Muerte, the Queen of the Land of the Remembered, and Xibalba, the King of the Land of the Forgotten -- both guardians of the souls of all our dearly departed who also happen to be sparring wife and husband. Xibalba is bored with the tedium of his kingdom and wants to take over the fiesta-land ruled by his wife. And so he proposes a wager: they randomly select three kids -- two boys and a girl, and all of them great friends and playmates -- and they try to see how destiny will lead them in the name of love. Will the boy who is a sensitive singer now being trained to become the greatest matador in the world win the girl's heart? Or will the boy who has the courage and the fighting spirit of a thousand armies emerge victorious? Manolo, the singing matador, is La Muerte's champion, and Joaquin, the soldier, is Xibalba's. They fall for the girl Maria. "Let the best man win," Joaquin tells his best friend Manolo. It is of course sad to see good friends become rivals. But the bet is on, and the story rolls out into a delightful amalgam of a believable love story, a movie musical (featuring contemporary songs! that rendition of Radiohead's "Creep" will haunt me forever), a showcase of dozens of delightful minor characters who

all steal the spotlight, and insights about carving out a path for oneself (among others) that do not feel like moral lessons. Spinning all of these is an animation style that looks fresh and new: the characters look like wooden puppets at play in candy land, but animated with the vibrance of the "life" in its title. I love this film. I wish more people would watch it. There were only ten people in the theatre I watched it in, and it felt like a disservice to this gem of a film. It's better than what Pixar is churning out these days.

#RoadToOscar

Labels: film, oscar

[0] This is Where You Bite the Sandwich

Monday, October 20, 2014

6:17 PM |

Noteworthy Dialogue: From Ben Stiller's The Secret Life of Walter Mitty (2013)

6:17 PM |

Noteworthy Dialogue: From Ben Stiller's The Secret Life of Walter Mitty (2013)

Walter and Sean spot an elusive ghost cat in the Himalayas. They huddle behind Sean's camera, and Walter waits for him to take a photo. Sean stares at the cat for a long time.

Walter:

Walter and Sean spot an elusive ghost cat in the Himalayas. They huddle behind Sean's camera, and Walter waits for him to take a photo. Sean stares at the cat for a long time.

Walter: When are you gonna ... take it.

Sean: Sometimes I don't... If I like a moment, I mean me, personally, I don't like to have the distraction of a camera. I just wanna stay in it.

Walter: (After a beat) Stay in it.

Sean: Yeah, right there. Right here.

Labels: film, life, quotes

[0] This is Where You Bite the Sandwich

Sunday, October 19, 2014

3:09 PM |

Noteworthy Dialogue: From John Curran's The Painted Veil (2006)

3:09 PM |

Noteworthy Dialogue: From John Curran's The Painted Veil (2006)

Kitty:

Kitty: "For God’s sake, Walter, will you stop punishing me! … Do you absolutely despise me?"

Walter: "No, I despise myself."

Kitty: "Why?"

Walter: "For allowing myself to love you once."

Ouch.Labels: film, life, love

[0] This is Where You Bite the Sandwich

Saturday, October 18, 2014

The race for the 87th Academy Awards has essentially started with all the online punditry abuzz with each new screening -- and as usual, I want to do my annual unflagging attempt to seeing all possible films in contention, even before the official nominations come on January. This blog series aims to chronicle this effort.

I have never before watched any film directed by Jean-Pierre and Luc Dardenne, fearful that I might not be able to hack any of their grim social realism. But here I was, finally watching the Dardenne brothers'

Deux Jours, Une Nuit (2014), Belgium's current submission to the Oscars, and finally I feel grateful for having overcome my own cinematic hesitance. The film very much feels like seeing a stripped down version of one of my favourite feel-good movies, Audrey Wells'

Under the Tuscan Sun. In that 2003 film, Diane Lane plays an American writer who falls into the deepest of despairs, only to find herself having an accidental splendid new life in the beautiful Italian countryside. Hollywood fodder, of course, but I have always responded to that film's golden promises, if only because I want to see the grimness of everyday life processed through rose-colored glasses. The Dardennes don't offer any rose-colored glasses at all. Their filmmaking is stark and spare, with a pace and mechanism to it that feels almost voyeuristic, bordering on the documentary. And all that felt exhilarating to me. We follow Marion Cotillard's blue collar worker Sandra who has been battling a crippling case of depression, necessitating medical leave from her work. (Doing what exactly, we have no idea.) On the eve of her return to her job, a Friday, she gets a call informing her that she has been made redundant at work. She also learns that her fellow workers were made to vote between keeping her, or keeping a 1,000 euro bonus. (Of course, they chose their bonus.) But her employer has given her reprieve. She has the chance of getting a new round of voting on Monday. Now, all she has to do is to convince the majority to give up their bonuses to keep her job. And the film follows her as she does her excruciating round of visiting each co-worker, begging them to reconsider. Some are understanding, some are angry, some don't want to see her at all, and some are downright violent and hostile. Her journey becomes like a microcosm of human behaviour. All the while, the film keeps a firm gimlet eye on Cotillard's character as she juggles through the most tumultuous of emotions, battling her darkness within, pleading for reconsideration, and understanding quite well when she doesn't get it -- and hating herself for begging, and knowing that if she doesn't fight, all is lost. What was disconcerting about the film was how the Dardennes -- and Cotillard -- telegraphed all these so easily and meaningfully that Sandra's dilemma becomes our dilemma: we could easily see ourselves in her shoes -- and the worst part is, we could easily see ourselves in her co-workers' shoes, too. What makes us human? What is pity? What is need, and what is selfishness? Will we give up something we desperately need in order to consider the plight of another human being? The film does not offer any easy choices. But I like how it ended. I like the hard-earned epiphany Sandra gets in the end, and in a sense, no matter how dour the story is, it is still a moving experience.

Best Foreign Language Oscar Chances: Very good.

#RoadToOscar

Labels: film, oscar

[0] This is Where You Bite the Sandwich

Thursday, October 16, 2014

1:52 AM |

1993 Best Foreign Language Film Reloaded: How to Listen and Fall in Love

1:52 AM |

1993 Best Foreign Language Film Reloaded: How to Listen and Fall in Love

Part 6 of a Series

And finally we come to the last film nominated for Oscar's Best Foreign Language Film in 1993.

There is no overt story being told in Trần Anh Hùng's sensuous

The Scent of Green Papaya, Vietnam's nominated entry (its first, and so far its last). Although once you let the film's rhythm embrace you, by and by, you do get a certain thread of a storyline -- and yet you quickly get that this is a film that is, above all, about atmosphere. The story follows a girl named Mui, newly arrived from the countryside, who comes to a neighbourhood somewhere in the outskirts of a city, and we get the impression that this is Vietnam before the fall of Saigon. Mui is taken in as a servant by a family -- the mother is a patient smalltime businesswoman, her husband seems to be a lout, their three young sons are consumed by the boredom and itches of adolescence, and their old cook stands in the margins, observing all. The film follows Mui's days and nights in this household, observing the minutiae of her life, until a shift happens midway where we finally see her as a young woman falling in love with the young master of the house she is currently serving.

I remember this film most as if it was something being told by way of a dream, or at least that brief moment we get upon waking where we are still floating in the boundaries of a dream before the claws of reality finally take hold of our senses. I think this is the impression I got of the film 21 years ago when I first saw it because it is largely a very quite movie, with snatches of dialogue here and there, but one that is also aware of the power of music and ambient sound. That carefully orchestrated mix of sound and music -- in particular Debussy's "Clair de Lune" -- are the cues with which we see things through Mui's senses. The feel and smell of green papaya seeds. The warbling of crickets. The crackle of sautéed vegetables in a wok. The sound of glass cracking. The sight of ants in a warpath. And sometimes above this beautiful mix of meditative silence and domestic sound, the drone of invisible warplanes in the distance.

You come away from Trần Anh Hùng's film knowing you have been made privy to an experience like no other. And this is what distinguishes

Scent of Green Papaya high and above the other films in the nominee list. It is the most cinematic of them all, and pushes the art form towards aesthetics that are not easily handled, but here we see it displayed in virtuosic grandness -- but a grandness that springs from little things and small observations.

This film should have won the 1993 Oscar for Best Foreign Language Film. That the least of them all -- Fernando Trueba's

Belle Epoque -- won is testament once again of Oscar's overwhelming Euro-centricity, where France, Italy, Germany, and Spain dominate regardless of how the rest of world cinema fares. Three Asian films triumphed in 1993, and a poorly made Spanish sex comedy gets the prize.

But to get back to my main point. Sure, the Asian film often gets short shrift in the Oscars. But what of the Filipino film? Will we finally get Oscar recognition with Lav Diaz's

Norte, Hangganan ng Kasaysayan? That's my next post.

Labels: film, oscar

[0] This is Where You Bite the Sandwich

12:54 AM |

1993 Best Foreign Language Film Reloaded: How to Hide in the Closet

12:54 AM |

1993 Best Foreign Language Film Reloaded: How to Hide in the Closet

Part 5 of a Series

What a wonderful romp this film was. This was the first film of the Oscar-honored bunch that I saw, 21 years ago, and it has retained its charms after all these years. Coming a year before

Eat Drink Man Woman and a year after

Pushing Hands,

The Wedding Banquet would complete a kind of trilogy depicting the small upheavals in Taiwanese family lives. These films are as observant as the best of Yasujiro Ozu's but with none of the distant formality: Ang Lee's early films are drenched in food, cosmopolitan quirkiness, and dramatic gestures, and all these to excavate the often unsubtle negotiations between the traditional and the modern in the Taiwanese family.

Temperamentally different by miles and miles from any of the other films in the nominee list so far, Ang Lee's

The Wedding Banquet was a surprise Oscar contender. That Taiwan submitted it given the unapologetic -- and positive (

gasp!) -- way the film tackled the gay relationship central to the story was already a surprise. That the Oscars would also bite was another surprise, although 1993 was also the year Jonathan Demme's

Philadelphia came out as a major mainstream offering.

Philadelphia's serious subject matter -- homosexuality and AIDS -- proved to be something Oscar could not ignore, and soon dutifully handed over an acting statuette to Tom Hanks for what was considered a "brave" performance as an AIDS victim seeking redress.

The Wedding Banquet is the lighter side of the gay spotlight that year: no victims here, no troubling darkness -- only the hijinks of a domestic drama involving a closeted gay Taiwanese businessman, his intrepid American lover, his doting parents who keep expressing a wish for him to get married, and finally his desperate Chinese tenant, a female painter who becomes the willing partner in a plot hatched by the two gay men to get the parents off their backs. There will be a fake marriage for a green card. A surprise wedding ceremony soon complicates things -- and the twisting and turning of these complications are what keeps the suspense for the movie.

I love the lightness of Ang Lee's touch in his early films, the way he manages to navigate through his culture to find insights to universal dilemmas. The rest of the 1990s would see him try to do the same for cultures outside of his own --

Sense and Sensibility in 1995,

The Ice Storm in 1997, and

Ride with the Devil in 1999, before returning to his Chinese roots and finally making a definite mark in 2000 with

Crouching Tiger Hidden Dragon -- but those early 1990s films are where he has poured his heart out.

It shares with Chen Kaige's

Farewell My Concubine the

menage a trois theme (two men in a relationship and the woman invading it!) at the center of their complications, but

The Wedding Banquet is actually the better film. It's more complex in its mapping of its human stories, which is easily overlooked because of its contemporary setting and its comedy. The historical seriousness and the elaborately costumed drama of

Concubine, however, are blinding flashes of fireworks that hide the fact there's not much there.

Next: Trần Anh Hùng's

The Scent of Green Papaya...

Labels: film, oscar, queer

[0] This is Where You Bite the Sandwich

Tuesday, October 14, 2014

9:08 PM |

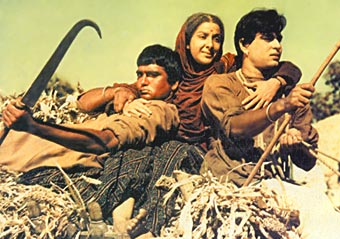

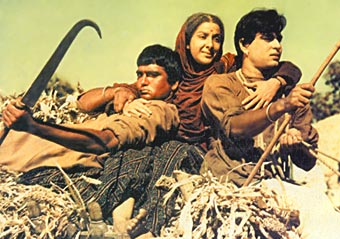

1993 Best Foreign Language Film Reloaded: How to Survive Chinese History

9:08 PM |

1993 Best Foreign Language Film Reloaded: How to Survive Chinese History

Part 4 of a Series

I approached Chen Kaige's

Farewell My Concubine with some trepidation when I watched it again last night, knowing full well how much I disliked it when I first saw it some 21 years ago. I suppose my earlier reaction was one borne out of the inevitable disappointment that came from much-too-high expectations.

But I remember sorely wanting to

like this film. Gong Li then was my recently discovered film siren -- someone I latched on to in my younger "Fuck-Hollywood-The-Rest-of-the-World-Has-Much-to-Offer" years. I was also just discovering the vastness of Asian cinema, and I was devouring the works of Jafar Panahi, Ang Lee, Wong Kar-Wai, Zhang Yimou, Akira Kurosawa, Yasujiro Ozu, and so many others. That the film had won the Palme d'Or from Cannes also sent my expectations to the stratosphere; its gay subtext also proved quite inviting.

And then I saw it, and I felt let down:

Farewell My Concubine seemed like a mess. Its promise of a story set to epic scale seemed dwarfish in execution. The characters and their stories did not draw me in. And, worst of all, it had none of the visual poetry of Zhang Yimou's films. I had just seen

Raise the Red Lantern, and I was overwhelmed by its lyricism, its sense of history unfurling in uncanny domestic melodrama. Yimou was my idea of a perfect Chinese film from the Fifth Generation of filmmakers. Kaige's effort seemed like the product of a crasser cousin: pompous, overlong, rough, uninvolving.

So I surprised myself for liking the film this time around. What had changed in the interim? Perhaps my middle-agedhood? (I'm quite old now, or at least, old

enough.) Perhaps I have seen so much more of life (that cliche...), and have felt so much more the frail tango of desire and recrimination we do with the people we love? Perhaps I have known so much more the cruel subtleties of loving and the many languages of betrayal?

Because it is the convoluted relationships between the film's three main protagonists that I have responded to so much more now. I still though Kaige's execution to be rough, but this time, it felt more in keeping with the theme of its story. It follows the trajectory of the lives of two Beijing Opera performers -- one who plays the king and the other the consort in the popular play "Farewell My Concubine" -- from their harsh training in childhood to the harsher reception they get in the real world as history unfolds in modern China. The central motif, of course, is the dramatic details of the play they have been performing for all their lives. We see how the motif plays out in their lives outside of the stage as they confront the changes in society, from the fall of the monarchy, to the rise and fall of the Koumintang, to the invasion by the Japanese, to the rise of Communism, and the complete ravaging of the Cultural Revolution. Their lives is made even more complicated by the entry of a woman -- a prostitute played ably by Gong Li -- who has married the "king" (played by Zhang Fengyi) and has set the "concubine" (played immaculately, like a secret dragon, by Leslie Cheung) into an extended jealous fit. How subtle the ways they manipulate each one in their complicated triangle! And how equally subversive how they demonstrate their love and hate as well! I adored the complexity of their untidy melodrama.

Compared to the similar shenanigan's in Trueba's melodrama, Kaige's film easily trumps the Spanish one, and the latter suddenly seems like a horny teenager's depiction of sexual politics.

Farewell My Concubine is smart, and is easily the better-made film.

Belle Epoque's Oscar feels like frivolous win.

Next: Ang Lee's

The Wedding Banquet...

Labels: film, oscar

[0] This is Where You Bite the Sandwich

4:15 PM |

1993 Best Foreign Language Film Reloaded: How to Be a Wartime Poet

4:15 PM |

1993 Best Foreign Language Film Reloaded: How to Be a Wartime Poet

Part 3 of a Series

Of all five contenders to the Best Foreign Language Film Oscar in 1993, there was only one film in the course of that Oscar season that I hadn't seen, simply because it was impossible to get. That would be Paul Turner's

Hedd Wyn, the first Welsh film to be nominated for an Oscar. (They would make a repeat of that nomination six years later, in 1999, with Paul Morrison's

Solomon and Gaenor.) The United Kingdom had begun sending non-English entries to the Oscars two years prior, in 1991, and

Hedd Wyn would be their second entry after skipping a year. I had always believed that its nomination was borne out of some curiosity in the Academy: the United Kingdom sending in an entry for Best Foreign Language Film. Seeing it now for the first time, my old suspicions ring true.

It helped, of course, that Turner's is a well-made film -- safe and non-controversial in the way the British makes them. (Think

The King's Speech.) It also has lyrical poetry and a brutal war -- two things that shout "prestige!"

Hedd Wyn is basically the story of the real-life Welsh poet Ellis Humphrey Evans, known more popularly in Wales as the titular name. A poet made of country stock and sensibilities, he soon came to prominence with his heady verses that proved critically popular. But his nascent rise in the local writing world coincided with the outbreak of World War I. A pacifist who did not believe in killing other people, our dear poet resisted enlisting -- which proved an unpopular stance in his small town. He does eventually make it to the trenches, and the scenes of his battlefield death [

this is not a spoiler: the film begins with this, and dips into it at length] is spliced beautifully with his winning one of Wales' biggest literary prize. (The film actually made me realise how you can stage a low-budget war by employing mostly close-ups and smokescreen and the sound of mortar and gunfire.) It is basically the Welsh version of

All Quiet on the Western Front complete with its anti-war sentimentality. Handsomely made, it is however more stuffy Masterpiece Theatre for me than something that should be considerably breaking new ground in cinematic arts. In other words, it is much too safe and genteel, and belongs right in there with the best of Hallmark films -- an uncompelling treatment of a supposedly important subject. It is still watchable, but it has not aged well.

Next: Chen Kaige's

Farewell My Concubine...

Labels: film, oscar

[0] This is Where You Bite the Sandwich

Monday, October 13, 2014

9:44 PM |

1993 Best Foreign Language Film Reloaded: How to Sleep With Four Sisters

9:44 PM |

1993 Best Foreign Language Film Reloaded: How to Sleep With Four Sisters

Part 2 of a Series

In 1993, something strange happened to the Best Foreign Language Film lineup for the Oscars. It was surprisingly Asian-centric, after decades and decades of the Oscars being enamoured with European fare. It was a year that was kind to Asian films altogether. The one enduring Asian movie star was immortalised in the popular and well-received biopic,

Dragon: The Bruce Lee Story, starring Jason Lee and directed by Rob Cohen. And Hollywood also produced one mainstream fare that defied expectations: Wayne Wang's adaptation of Amy Tan's bestselling

The Joy Luck Club was a critical hit, and was most unusual for having gathered together some of the best-known but least hired Asian-American actresses. To a lesser degree, there was David Cronenberg's adaptation of David Henry Hwang's play

M. Butterfly, with Jeremy Irons and John Lone. Other releases included Gurinder Chadha's

Bhaji on the Beach and Tsui Hark's

The Green Snake. The Cannes Palme d'Or also went to Chen Kaige's

Farewell My Concubine that year, a prestige it shared with Jane Campion's

The Piano. It was such a popular hit that Gong Li started getting notices as a possible Best Supporting Actress nominee. The film went on to win Best Foreign Film at the Golden Globes. Over at the Berlin Film Festival, its Golden Bear also went to two Asian films: Xie Fei's

The Women from the Lake of Scented Souls and Ang Lee's

The Wedding Banquet.

Three films from the continent being nominated for the Oscars wasn't surprising. Consider the contenders: Chen Kaige's

Farewell My Concubine from Hong Kong, Trần Anh Hùng's

The Scent of Green Papaya from Vietnam, and Ang Lee's

The Wedding Banquet from Taiwan. Three magnificent films whose reputation has not been lessened by the years. They competed for the Oscar statuette along with Fernando Trueba's

Belle Époque from Spain and Paul Turner's

Hedd Wyn from United Kingdom. The Asian films dominated the conversation that year, but true to the Euro-centric nature of the Oscars, guess which film won: Spain's entry. Let us consider each nominated film again.

This was the eventual Oscar winner, and I remember watching the telecast and feeling miffed when its title was announced. I remembered watching Trueba's film in 1994 with some trepidation. I was a teenager fresh from high school, and all I was hearing about

Belle Epoque was how "sexy" it was, how deliciously sinful. After I'd seen it, it didn't do much for me -- although I quite agreed the adjectives hoisted on it proved more or less true. But that's to be expected from a story about a handsome young army deserter at the height of the Spanish Civil War who finds himself somehow living in the farmhouse of an older gentleman who just happened to have four beautiful daughters visiting him from Barcelona. They turn out to be all ravishingly beautiful and temperamentally different from each other, which only makes the young man decide to stay on, in hopes of winning one of the girls. He just doesn't win one sister, he manages to bed them one after the other in a series of fortunate circumstances until finally he makes his fate by acknowledging the one who loves him the best.

Seeing it again, it strikes me as being -- ironic for its themes -- a conservatively assembled film, quite an old-fashioned effort that doesn't push the cinematic envelope much. It's not scintillating cinema at all, but it wallows prettily in its carnal fantasy. It has lots of humour thrown in for good measure, plus a stick or two of historical reflections that can persuade the viewer to think that perhaps all these is some kind of commentary about the deep-rooted schisms of Spanish society before Franco. There

has to be since it cannot just be all about beautiful women and beautiful men and rambunctious sex and some other shenanigans. But it's sad to note that, more than twenty years later, we find that there's ultimately not much there in the film: it's just a pleasant, inoffensive sex comedy that has the brilliance of a lazy

siesta.

Next up: Paul Turner's

Hedd WynLabels: film, oscar

[0] This is Where You Bite the Sandwich

4:46 AM |

Oscar and the Asian Film

4:46 AM |

Oscar and the Asian Film

Part 1 of a Series

In all my years of watching the Oscars and following the race among the contenders that precede each annual telecast of Hollywood's glamourised pat-on-the-back, I have been drawn to one category more than the usual: the award for Best Foreign Language Film.

When I was a younger cinephile, the award struck me as one that was the very illustration of the "magnanimity" of the Academy, which has chosen to single out a film (out of five nominees) that does not come out of the usual American cinematic machinery, to shine some spotlight on the national cinema of some other country that was not the United States, nor its close cousin the United Kingdom.

It also promised me this possibility: here was an Oscar that can truly be won by a Filipino filmmaker. All we need to do, as the category's rules demand, is to have the country's institutional representative chose a title from among those who have undergone a week's worth of qualifying run, then submit the title to the Academy, and then wait for the Academy's own subcommittee overseeing the category to whittle a long-list of usually 70+ titles, to a short list of nine, out of which the final five are chosen.

The older cinephile in me has since realised that all these is easier said than done. More than politics are involved in the grind towards the selection of the nine.

There is also the relentless campaign to get noticed. How does one film among 70 get noticed? Doing the festival circuit -- Cannes, Berlin, Venice, Toronto, Sundance, New York -- is one answer: the better films get better notices, and hopefully word-of-mouth will carry the title through the looong race. Compiling the better notices from important film critics is another. At year's end, the circles they run in usually produce their top-tens and unveil the winners of their award listings. The more a film gets mentioned, the more you are "in the conversation."

It is a trickier process for a "foreign language film," given the bias towards Hollywood fare in these considerations. The one Filipino film, I think, that came closest to surviving this process was Aureaus Solito's

Ang Pagdadalaga ni Maximo Oliveros, which won the coveted Teddy at the Berlinale and snagged a nomination at the Independent Spirit Awards, while getting generous attention from critics and list-makers. But when the 2006 Oscar's short list was finally revealed, the nominations went to Germany, Denmark, Algeria, Mexico, and Canada: two European countries, one African (a rarity -- but not a rarity for Algeria), one Latin American, and one North American (but a film that does have an Asian theme). In 2007, a film from a most unusual Asian country made the shortlist, but it was Kazakhstan's first attempt to submit a film to the Oscar -- and sometimes being a first-timer helps: at least it brings a heightening of attention by those who are voting. ("The first submission from that country, eh? Let's take a look...")

The Philippines has never won a competitive Oscar for Best Foreign Language Film, even when it has one of the oldest national cinemas in the world, and even when it actually started sending in submissions in 1956, the first year of the category when it went full-merit. (We sent in Lamberto Avellana's

Anak Dalita. Federico Fellini's

La Strada, from Italy, won.)

Before 1956, the Oscars did recognise certain foreign films as having been the best of their respective years -- but it was not a competitive award. In 1953, Manuel Conde's

Genghis Khan -- which had wowed the Venice Film Festival -- was considered for a special citation, but it never got the award. (No foreign film got the award that year.) In those pre-competitive years, only three countries ever merited Oscar distinction:

Italy (

Shoeshine in 1947 and

The Bicycle Thief in 1949),

France (

Monsieur Vincent in 1948,

The Walls of Malapaga in 1950, and

Forbidden Games in 1952), and

Japan (

Rashomon in 1951,

Gate of Hell in 1954, and

Samurai: The Legend of Musashi in 1955). As far as Oscar was concerned, these were the only countries in the world aside from the U.S. and the U.K. that were making films in those years.

But the Philippines has not always sent in submissions. In the 1960s, we only sent twice: in 1961 with Gerardo de León's

The Moises Padilla Story, and in 1967 with Luis Nepomuceno's

Dahil sa Isang Bulaklak. In the 1970s, we only sent once: in 1976, with Eddie Romero's

Ganito Kami Noon, Paano Kayo Ngayon. In the 1980s, we only sent in twice: in 1984 with Marilou Diaz-Abaya's

Karnal, and in 1985 with Lino Brocka's

Bayan Ko: Kapit sa Patalim. Imagine all the other magnificent films in the First and Second Golden Ages of Philippine Cinema that went unsubmitted.

But we have regularly sent in submissions in the 1990s and thereafter, starting in 1995 with Carlos Sigiuon-Reyna's

Inagaw Mo ang Lahat, and followed by Tikoy Aguiluz's

Segurista in 1996, Marilou Diaz-Abaya's

Milagros in 1997 and

Sa Pusod ng Dagat in 1998, Gil Portes's

Saranggola in 1999, Rory Quintos'

Anak in 2000, Gil Portes again with

Gatas... Sa Dibdib ng Kaaway in 2001 and

Mga Munting Tinig in 2002, Chito Roño's

Dekada '70 in 2003, Mark Meily's

Crying Ladies in 2004, none in 2005 (because of the Film Academy of the Philippines' reasoning that the Oscars were not notified of their change in office address -- thus the "non-delivery" of the official invitation to submit), Auraeus Solito's

Ang Pagdadalaga ni Maximo Oliveros in 2006, Adolfo Alix Jr.'s

Donsol in 2007, Dante Nico Garcia's

Ploning in 2008, Soxie Topacio's

Ded na si Lolo in 2009, Dondon Santos's

Noy in 2010, Marlon Rivera's

Ang Babae sa Septic Tank in 2011, Jun Robles Lana's

Bwakaw in 2012, Hannah Espia's

Transit in 2013, and now Lav Diaz's

Norte, Hangganan ng Kasaysayan in 2014. Sometimes, some of the title sent for consideration can be cause for much head-scratching, with

Noy standing out as the worst possible contender. And what gives the popularity of Gil Portes whose cinema is, at best, merely "decently-made"?

Our own politics obscure enough our chances for Oscar gold, so one can only imagine the vagueness that transpires from the bigger politics of the international film world. In the given morass of choices and politicking, I can understand an Academy member, who is tasked to be part of the special committee to sift through the gargantuan number of foreign language film submissions, to decide to fall in with the easier alternative of dealing only with national cinemas of considerable track record, or of considerable "undeniability." By that, we mean the countries of Europe, of course, with token representations of the often-cannot-be-ignored countries from other continents (South Africa and Algeria from Africa, Japan and China from Asia's Far East and Israel from the Middle East, Argentina and Mexico from Latin America, and that's basically it.) The stray entry from the unlikely country not usually within Oscar's radar (Cuba, Vietnam, Nepal, Kazakhstan, Cambodia, Vietnam, Ivory Coast, and Nicaragua) becomes the "surprise" tokenism that assures everyone the world has been gone over with a fine-tooth comb.

But here are some statistics:

Twenty-four (24) European countries have so far merited nominations. Compare

that with only three countries with nominations from Africa. Or only nine countries with nominations from Latin America. (Uruguay's nomination in 1992 was, however, rescinded. And there is the curious case of Puerto Rico, essentially part of the United States, but which garnered a nomination in 1989.) From Asia, there are four countries with nominations from East Asia, two from South Asia, two from Southeast Asia, and four from the Middle East -- 12 in all. Canada as the lone North American country that is not the U.S. has been nominated several times (7 times to be exact).

Almost

all European countries have been nominated --

except for Ireland, Portugal, and Romania for the major ones (quite a surprise), and Luxembourg, Albania, Cyprus, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Turkey, Bulgaria, San Marino, Vatican City, Monaco, Andorra, Armenia, Belarus, Azerbaijan, Liechtenstein, Lithuania, Malta, Moldova, and the Ukraine. And I'm not exactly sure how to consider Croatia, Montenegro, Serbia, and Slovenia, because as constituents parts of the former Yugoslavia, they managed to secure six nominations for that (now-nonexistent) country. The same goes for Slovakia, which, as part of the former Czechoslovakia, also garnered six nominations. Since separating from its sister country, it has not garnered any nominations all its own, but the Czech Republic has three nominations thus far.

From a total of 331 nominations (including the special ones) since 1947, 248 or 75% have gone to European countries. Asia clocks in a very distant second with 45 nominations, or 14%. Latin America follows with 24, or 7%. Africa and North America's Canada, with seven nominations each, contribute 2% respectively.

Of the top five countries with most nominations, France leads with a record 38, and Italy follows with 30. (But both share an award in a 1950 co-production with René Clément's

The Walls of Malapaga.) Spain is third with 20, and then Germany (including nominations for West Germany) with 18. Japan is fifth with most nominations with 15. But Sweden and Russia (including nominations for the Soviet Union) follow very closely with 14 nominations each.

Among the winners, 54 Oscars, or a whooping 81%, have gone to European countries. Only 6 Oscars, or 9%, have gone to Asian countries. Africa, with three wins, constitutes 4%. Argentina's two wins constitute 3% for Latin America. Canada's one win is the remaining 1%.

Taking a look at the European winners, Italy is the over-all champion with 14 wins, followed by France with 12 wins. Russia/Soviet Union and Spain come close with 4 wins each. Sweden, the Czech Republic, Germany, the Netherlands, and Denmark follow with three wins (including two for the Czech Republic, when it was part of Czechoslovakia). Switzerland and Austria have two wins, and there are the singular wins for Hungary and Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Japan, with four wins, has the most Oscars for a non-European country, followed by Argentina with its two wins.

In other words, the Oscars is very much a Europe-centric affair.

As a matter of curiosity, I took note of the years where Europe essentially blocked off the rest of the world with nominations, expecting to find a rarity. To my surprise, there were

12 years (out of 57 since 1956) -- specifically 1958, 1959, 1966, 1968, 1970, 1978, 1979, 1985, 1986, 1987, 1992, and 1996 --

where there were only European nominees. That's a lot of years of being blind from the rest of world cinema.

I want to focus for now on the Asian film, however, and how it has fared exactly with Oscars. When I talk of the Asian film, I consider the term with much respect to geography, and mostly considering the imprecise divide provided by the Urals. Hence, the Asian film does not only include those from East Asia (China, Japan, Taiwan, South Korea, North Korea, Mongolia, Hong Kong, and Macau), or Southeast Asia (the Philippines, Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand, Singapore, Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos, Burma/Myanmar, Brunei, East Timor, and Papua New Guinea), or South Asia (India, Sri Lanka, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Nepal, and Bhutan) -- but also, in my estimation, and perhaps problematically so, the films from the Middle East (which includes Israel, Palestine, Iran, Iraq, Saudi Arabia, Yemen, Oman, United Arab Emirates, Qatar, Kuwait, Afghanistan, Tajikistan, Kyrgystan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, Syria, Lebanon, and Jordan). Turkey, for all its wishes to be considered part of Europe, has not been included.

I have attempted to consider the Asian Oscar in terms of the chronological in nominations. The countries below are listed according to the first time they were ever nominated for a Best Foreign Language Film Oscar. I have endeavored to specify the number of wins and nominations, taking note of the films nominated for each particular year. Asterisks (*) denote winning films.

JAPAN

Wins:

JAPAN

Wins: 4 (including 3 pre-competitive special citations)

Nominations: 15

1951

Rashomon*

1954

Gate of Hell*

1955

Samurai, The Legend of Musashi*

1956

Harp of Burma

1961

Immortal Love

1963

Twin Sisters of Kyoto

1964

Woman in the Dunes

1965

Kwaidan

1967

Portrait of Chieko

1971

Dodeska-den

1975

Sandakan No. 8

1980

Kagemusha

1981

Muddy River

2003

The Twilight Samurai

2008

Departures*

INDIA

Wins:

INDIA

Wins: 0

Nominations: 3

1957

Mother India

1988

Salaam Bombay!

2001

Lagaan

ISRAEL

Wins:

ISRAEL

Wins: 0

Nominations: 10

1964

Sallah

1971

The Policeman

1972

I Love You Rosa

1973

The House on Chelouche Street

1977

Operation Thunderbolt

1984

Camila

2007

Beaufort

2008

Waltz With Bashir

2009

Ajami

2011

Footnote

CHINA

Wins:

CHINA

Wins: 0

Nominations: 2

1990

Ju Dou

2002

Hero

HONG KONG

Wins:

HONG KONG

Wins: 0

Nominations: 2

1991

Raise the Red Lantern

1993

Farewell My Concubine

VIETNAM

Wins:

VIETNAM

Wins: 0

Nominations: 1

1993

The Scent of Green Papaya

TAIWAN

Wins:

TAIWAN

Wins: 1

Nominations: 3

1993

The Wedding Banquet

1994

Eat Drink Man Woman

2000

Crouching Tiger Hidden Dragon*

IRAN

Wins:

IRAN

Wins: 1

Nominations: 2

1998

Children of Heaven

2011

A Separation

NEPAL

Wins:

NEPAL

Wins: 0

Nominations: 1

1999

Caravan/Himalaya

PALESTINE

Wins:

PALESTINE

Wins: 0

Nominations: 2

2005

Paradise Now

2013

Omar

KAZAKHSTAN

Wins:

KAZAKHSTAN

Wins: 0

Nominations: 1

2007

Mongol

CAMBODIA

Wins:

CAMBODIA

Wins: 0

Nominations: 1

2013

The Missing Picture

(There is the special case of the Soviet Union in 1975 when it won for

Dezu Uzala, which was a Japanese co-production directed by the great Akira Kurosawa. It is a very much an Asian film, but for the sake of clean statistics, I am not considering it.)

But what can we learn from the nominations above?

First, it's good to be Japan. But Japan was the first Asian country to really make the rounds of the international festival circuit, and the films of Akira Kurosawa (and later on, Yasujiro Ozu) essentially opened the eyes of the world to the possibilities of Japanese cinema. It has earned the right of "first consideration," so to speak. Any Japanese film, by virtue of that long tradition of recognised excellence, will always be something for Oscar to take a look at. Any year is theirs to lose in terms of being nominated, the same privilege accorded to Italy and France.

Second, it's good to be the new kid on the block. Vietnam, Nepal, and Kazakhstan were curious first timers when they got their first nominations. They have not been nominated since their years.

Third, it pays to be quirky, especially if quirky has something to do with some dark historical material. Cambodia has submitted twice before it hit pay dirt: in 1994 with

Rice People, and then in 2012 with

Lost Loves, both with no nominations. But 2013's

The Missing Picture was quirky: it was a documentary of Pol Pot's purge of the country, but done in claymation. It borrowed from Israel's technique of 2007:

Waltz With Bashir was an animated documentary about Israeli soldiers fighting a godless war in Lebanon. Those things get noticed.

Fourth, it's good to be a country that is always headline news. For better or for worse, Palestine has instant name recall. It is always newsworthy. I wish the Philippines submitted something in 1986, when its People Power revolution made the country a household name all over the world. That could have translated to a nomination. We didn't send anything. But then again, nor did we produce anything of considerable excellence.

Lumuhod Ka Sa Lupa! and

Donggalo Massacre, anyone?

Fifth, having one of the oldest national cinemas in the world does not mean anything. Take a look at India's meagre three nominations, and not one film by Satyajit Ray among them, although one of his film (

The Chess Players) did get submitted, but did not garner a nomination, in 1978.

Sixth, it pays to be a juggernaut in the American domestic box office. Ang Lee's

Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon -- Taiwan's submission in 2000 -- could not be denied its win. It was already angling for a much bigger prize -- the Best Picture Oscar itself -- but I guess Academy voters thought it safe, and more American, to give Lee's film the lesser statuette.

Gladiator won instead.

Seventh, it pays to be Ang Lee. It has submitted a total of 40 times, but Taiwan only gets nominations every time it submits a film directed by Ang Lee.

And so, it is mostly a hit-and-run affair with Oscars and the Asian film.

In 1993, however, a miracle happened. In a year that was kind to Asian film, three were nominated for the Oscars: Chen Kaige's

Farewell My Concubine from Hong Kong, Trần Anh Hùng's

The Scent of Green Papaya from Vietnam, and Ang Lee's

The Wedding Banquet from Taiwan. They competed for the Oscar statuette along with Fernando Trueba's

Belle Époque from Spain and Paul Turner's

Hedd Wyn from United Kingdom. The Asian films dominated the conversation that year, but guess which won...

I'm going to see all five 1993 nominees again, and see how each measure up today. Did the right film win?

To be continued...Labels: film, oscar

[0] This is Where You Bite the Sandwich

GO TO OLDER POSTS

GO TO NEWER POSTS

8:12 PM |

The Dead in Riverdale

8:12 PM |

The Dead in Riverdale

7:42 PM |

Horror Hits and Misses

7:42 PM |

Horror Hits and Misses

4:10 PM |

Notes on a Short Story: The Flicker

4:10 PM |

Notes on a Short Story: The Flicker

6:13 PM |

Life is Lots and Lots of Bath Oils: An Appreciation of Nora Ephron

6:13 PM |

Life is Lots and Lots of Bath Oils: An Appreciation of Nora Ephron

12:02 AM |

The Color of Living

12:02 AM |

The Color of Living

6:17 PM |

Noteworthy Dialogue: From Ben Stiller's The Secret Life of Walter Mitty (2013)

6:17 PM |

Noteworthy Dialogue: From Ben Stiller's The Secret Life of Walter Mitty (2013)

3:09 PM |

Noteworthy Dialogue: From John Curran's The Painted Veil (2006)

3:09 PM |

Noteworthy Dialogue: From John Curran's The Painted Veil (2006)

11:45 PM |

Bad Weekend

11:45 PM |

Bad Weekend

1:52 AM |

1993 Best Foreign Language Film Reloaded: How to Listen and Fall in Love

1:52 AM |

1993 Best Foreign Language Film Reloaded: How to Listen and Fall in Love

12:54 AM |

1993 Best Foreign Language Film Reloaded: How to Hide in the Closet

12:54 AM |

1993 Best Foreign Language Film Reloaded: How to Hide in the Closet

9:08 PM |

1993 Best Foreign Language Film Reloaded: How to Survive Chinese History

9:08 PM |

1993 Best Foreign Language Film Reloaded: How to Survive Chinese History

4:15 PM |

1993 Best Foreign Language Film Reloaded: How to Be a Wartime Poet

4:15 PM |

1993 Best Foreign Language Film Reloaded: How to Be a Wartime Poet

9:44 PM |

1993 Best Foreign Language Film Reloaded: How to Sleep With Four Sisters

9:44 PM |

1993 Best Foreign Language Film Reloaded: How to Sleep With Four Sisters

4:46 AM |

Oscar and the Asian Film

4:46 AM |

Oscar and the Asian Film